Volume I (1605)

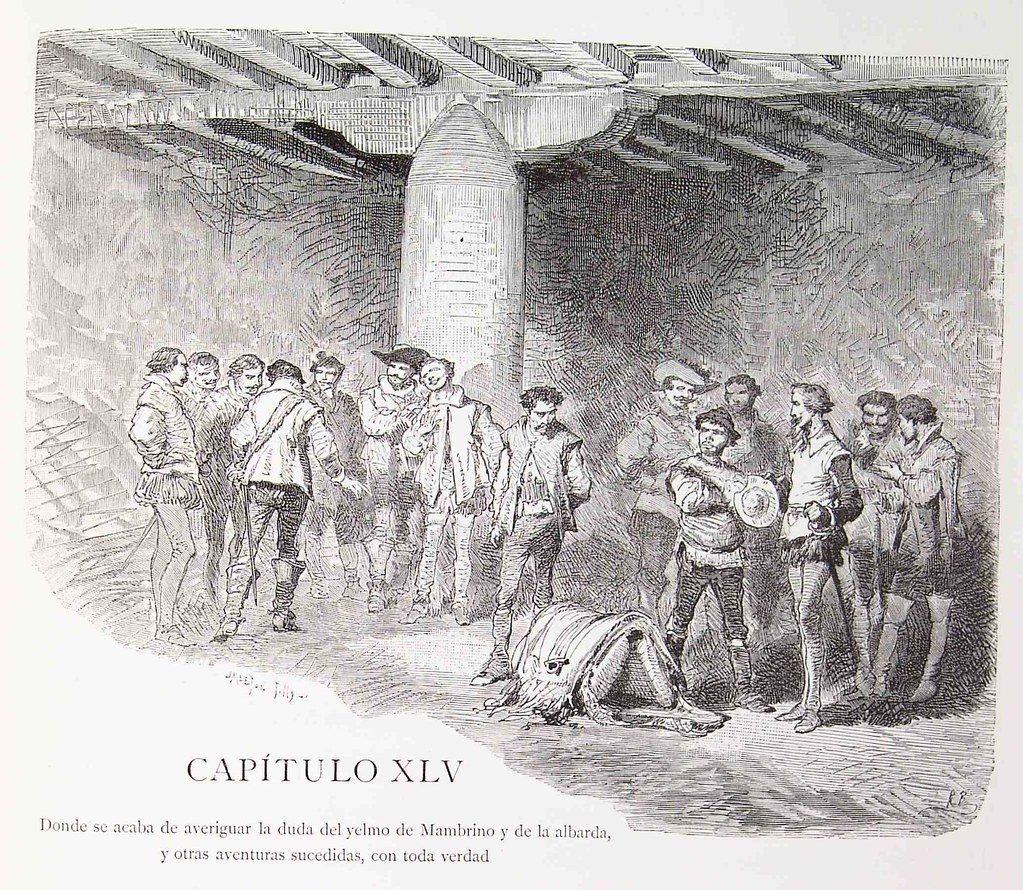

In which questions regarding the helmet of Mambrino and the packsaddle are finally resolved, as well as other entirely true adventures

“What do your graces think of what they’re saying, Señores?” said the barber. “These gentlefolk are still insisting that this isn’t a basin but a helmet.”

“And whoever says it is not,” said Don Quixote, “if he is a gentleman, I shall show him that he lies, and if he is a squire, that he lies a thousand times over.”

Our barber, who was present through all of this, knew Don Quixote’s madness so well that he wanted to encourage his lunacies and, by carrying the joke even further, give everyone a good reason to laugh, and so speaking to the second barber, he said:

“Señor Knight, or whoever you may be, you should know that I too follow your trade and have held my certificate256 for more than twenty years, and know very well all the tools of barbering, without exception; for a time I was even a soldier in my youth, and I also know what a helmet is, and a morion, and a full sallet, and other things related to soldiering, I mean to say, the kinds of weapons that soldiers use; and I say, barring a better opinion and bowing always to better judgment, that this piece in front of us, which this good gentleman is holding in his hands, not only is not a barber’s basin, but is as far from being one as white is from black and truth from falsehood; I also say that this, though a helmet, is not a complete helmet.”

“No, of course not,” said Don Quixote, “for half of it, the visor, is missing.”

“That is true,” said the priest, who had understood the intention of his friend the barber.

And the same was affirmed by Cardenio, Don Fernando, and his companions, and even the judge, if he had not been so involved in the matter of Don Luis, would have taken part in the deception, but he was so preoccupied by the gravity of his thoughts that he paid little or no attention to such amusements.

“Lord save me!” said the barber who was the target of the joke. “Is it possible that so many honorable people are saying that this is not a basin but a helmet? This seems to be something that could astonish an entire university, no matter how learned. Enough: if it’s true that this basin is a helmet, then this packsaddle must also be a horse’s harness, just as the gentleman said.”

“It looks like a saddle to me,” said Don Quixote, “but I have already said I shall not intervene in that.”

“Whether it is a packsaddle or harness,” said the priest, “is for Don Quixote to say, for all these gentlemen and I defer to him in matters of chivalry.”

“By God, Señores,” said Don Quixote, “so many strange things have happened to me in this castle on the two occasions I have stayed here, that if you were to ask me a question about anything in it, I would not dare give a definitive answer, for I imagine that everything in it is subject to enchantment. The first time I was greatly troubled by an enchanted Moor, and things did not go very well for Sancho at the hands of his companions, and last night I was hung by this arm for almost two hours, not having any idea of how or why I had fallen into that misfortune. Therefore, if I now become involved in so confusing a matter and give my opinion, it would be a rash judgment. As for what has been said regarding this being a basin and not a helmet, I have already responded to that, but as for declaring whether this is a saddle or a harness, I do not dare offer a final opinion: I leave it to the judgment of your graces. Perhaps because you have not been dubbed knights, as I have, the enchantments of this place will not affect your graces, and your minds will be free and able to judge the things in this castle as they really and truly are, and not as they seem to me.”

“There is no doubt,” responded Don Fernando, “but that Señor Don Quixote has spoken very well today, and it is up to us to decide the case; in order to make our decision a valid one, I shall take the votes of these gentlemen in secret and give a complete and clear report on the outcome.”

For those who were aware of Don Quixote’s madness, all of this was cause for a good deal of laughter, but for those who were not, it seemed the greatest lunacy in the world, especially the four servants of Don Luis, and Don Luis himself, and another three travelers who had just arrived at the inn and seemed to be members of the Holy Brotherhood, which was, in fact, what they were. But the one who was most confused was the barber, whose basin had been transformed into the helmet of Mambrino before his very eyes and whose packsaddle he undoubtedly thought would be turned into a horse’s rich harness; everyone laughed to see Don Fernando going from one to the other and taking his vote, having him whisper it into his ear so that each could declare in secret whether that jewel that had been so fiercely fought over was a packsaddle or a harness. After he had taken the votes of those who knew Don Quixote, he announced in a loud voice:

“The fact is, my good man, that I am weary of hearing so many opinions, because I see that no one whom I ask does not tell me that it is nonsense to say this is a donkey’s packsaddle and not the harness of a horse, even a thoroughbred, and so, you will have to be patient because despite you and your donkey, this is a harness and not a packsaddle, and you have presented and proved your case very badly.”

“May I never have a place in heaven,” said the second barber, “if all of your graces are not deceived, and may my soul appear before God with as much certainty as this appears to be a packsaddle and not a harness, but if you’ve got the might…and I’ll say no more; the truth is I’m not drunk, and I haven’t broken my fast except to sin.”

The barber’s simpleminded talk caused no less laughter than the lunacies of Don Quixote, who at this point said:

“All that can be done now is for each man to take what is his, and may St. Peter bless what God has given us.”

One of the four servants said:

“Unless this is a trick of some kind, I can’t believe that men of intelligence, which is what all of you are, or seem to be, can dare say and affirm that this isn’t a basin and that isn’t a saddle; but as I see that you do affirm and say it, I suppose there’s some mysterious reason why you claim something so contrary to what truth and experience show us, and I swear”—and here he came out with a categorical oath—“that not all the people alive in the world today can make me think that this isn’t a barber’s basin, and that isn’t a jackass’s packsaddle.”

“It might belong to a jenny,” said the priest.

“It doesn’t matter,” said the servant, “that’s not the point, the question is whether it is or isn’t a packsaddle, as your graces claim.”

Upon hearing this, one of the officers in the Holy Brotherhood who had come in and heard the discussion and dispute said in a fury and a rage:

“If that’s not a saddle, then my father’s not my father, and whoever says otherwise must be bleary-eyed with drink.”

“Thou liest like the base villain thou art,” responded Don Quixote.

And raising the lance that had never left his hands, he prepared to strike him so hard on the head that if the man had not dodged the blow, it would have knocked him down. The lance shattered on the ground, and the other officers, seeing their companion so badly treated, shouted for help for the Holy Brotherhood.

The innkeeper, who was a member,257 went in for his staff and sword and then stood by the side of his comrades; Don Luis’s servants surrounded him so that he could not escape during the disturbance; the second barber, seeing everything in a turmoil, seized his packsaddle again, and so did Sancho; Don Quixote drew his sword and charged the officers. Don Luis shouted at his servants to leave him and go to the assistance of Don Quixote, and Cardenio and Don Fernando, who were fighting alongside Don Quixote. The priest shouted, the innkeeper’s wife called out, her daughter cried, Maritornes wept, Dorotea was confused, Luscinda distraught, and Doña Clara in a swoon. The barber beat Sancho; Sancho pounded the barber; Don Luis, when one of his servants dared seize him by the arm to keep him from leaving, punched him so hard his mouth was bathed in blood; the judge defended him; Don Fernando had one of the officers under his feet and was trampling him with great pleasure; the innkeeper cried out again, calling for help for the Holy Brotherhood: in short, the entire inn was filled with cries, shouts, yells, confusions, fears, assaults, misfortunes, attacks with knives, fists, sticks, feet, and the spilling of blood. And in the midst of this chaos, this enormous confusion, it passed through the mind of Don Quixote that he had been plunged headlong into the discord in Agramante’s camp,258 and in a voice that thundered throughout the inn, he cried:

“Hold, all of you! All of you sheathe your swords, stop fighting, and listen to me, if you wish to live!”

At this great shout everyone stopped, and he continued, saying:

“Did I not tell you, Señores, that this castle was enchanted and that some legion of demons must inhabit it? In confirmation of which I wish you to see with your own eyes what has transpired here and how the discord of Agramante’s camp has descended upon us. Look, here they do battle for the sword, there for the horse, over there for the eagle, right here for the helmet, and all of us are fighting and all of us are quarreling.259 Come then, your grace, Señor Judge, and your grace, Señor Priest; one of you take the part of King Agramante and the other that of King Sobrino and make peace among us, because in the name of God Almighty it is a great wickedness for so many wellborn and distinguished people to kill one another for such trivial reasons.”

The officers of the Holy Brotherhood, who did not understand Don Quixote’s language and found themselves being mistreated by Don Fernando, Cardenio, and their comrades, did not wish to stop brawling, but the second barber did, since both his beard and his saddle had been damaged in the fracas; Sancho, like a good servant, obeyed every word his master said; and the four servants of Don Luis also stopped, seeing how little they had to gain from doing otherwise. Only the innkeeper insisted that the effronteries of that madman had to be punished, since he was always causing a disturbance at the inn. Finally, the clamor was stilled for the moment, and in the imagination of Don Quixote the saddle remained a harness until Judgment Day, and the basin a helmet, and the inn a castle.

When, at last, persuaded by the judge and the priest, everyone had made peace and become friends, Don Luis’s servants began to insist again that he come away with them immediately, and as he was discussing this with them, the judge spoke to Don Fernando, Cardenio, and the priest regarding what should be done in this matter, recounting what Don Luis had said to him. Finally, it was decided that Don Fernando should reveal his identity to Don Luis’s servants and tell them it was his wish that Don Luis accompany him to Andalucía, where his brother, the marquis, would welcome him as his great merit deserved, for it was evident that Don Luis would not now return willingly to his father even if he were torn to pieces. When the four men realized both the high rank of Don Fernando and the determination of Don Luis, they decided that three of them would return to report what had happened to his father and one would stay behind to serve Don Luis and not leave him until the other servants returned for him or he had learned what his master’s orders were.

In this fashion, a tangle of quarrels was unraveled through the authority of Agramante and the prudence of King Sobrino, but the enemy of harmony and the adversary of peace, finding himself scorned and mocked, and seeing how little he had gained from having thrown them all into so confusing a labyrinth, resolved to try his hand again by provoking new disputes and disagreements.

So it was that the officers stopped fighting when they heard the rank and station of their opponents, and they withdrew from combat because it seemed to them that regardless of the outcome, they would get the worst of the argument; but one of them, the one who had been beaten and trampled by Don Fernando, recalled that among the warrants he was carrying for the detention of certain delinquents, he had one for Don Quixote, whom the Holy Brotherhood had ordered arrested, just as Sancho had feared, because he had freed the galley slaves.

When the officer remembered this, he wanted to certify that the description of Don Quixote in the warrant was correct, and after pulling a parchment from the bosom of his shirt, he found what he was looking for and began to read it slowly, because he was not a very good reader, and at each word he read he raised his eyes to look at Don Quixote, comparing the description in the warrant with Don Quixote’s face, and he discovered that there was no question but that this was the person described in the warrant. As soon as he had certified this, he folded the parchment, held the warrant in his left hand, and with his right he seized Don Quixote so tightly by the collar that he could not breathe; in a loud voice he shouted:

“In the name of the Holy Brotherhood! And so everybody can see that I’m serious, read this warrant ordering the arrest of this highway robber.”

The priest took the warrant and saw that what the officer said was true and that the features in the description matched those of Don Quixote, who, enraged at his mistreatment by a base and lowborn churl, and with every bone in his body creaking, made a great effort and put his hands around the man’s throat, and if his companions had not hurried to his assistance, the officer would have lost his life before Don Quixote released him. The innkeeper, who was obliged to assist his comrade, rushed to his aid. The innkeeper’s wife, who saw her husband involved in a dispute again, raised her voice again, and Maritornes and her daughter immediately joined her, imploring the help of heaven and of everyone in the inn. Sancho, when he saw all of this, said:

“Good God! What my master says about enchantments in this castle is true! You can’t have an hour’s peace here!”

Don Fernando separated the officer and Don Quixote, and to the relief of both he loosened the hands of both men, for one was clutching a collar and the other was squeezing a throat; but this did not stop the officers from demanding that Don Quixote be arrested and that the others assist in binding him and committing him to their authority, as demanded by their duty to the king and the Holy Brotherhood, which once again was asking for their help and assistance in the arrest of this highway robber and roadway thief.

Don Quixote laughed when he heard these words and said very calmly:

“Come, lowborn and filthy creatures, you call it highway robbery to free those in chains, to give liberty to the imprisoned, to assist the wretched, raise up the fallen, succor the needy? Ah, vile rabble, your low and base intelligence does not deserve to have heaven communicate to you the great worth of knight errantry, or allow you to understand the sin and ignorance into which you have fallen when you do not reverence the shadow, let alone the actual presence, of any knight errant. Come, you brotherhood of thieves, you highway robbers sanctioned by the Holy Brotherhood, come and tell me who was the fool who signed an arrest warrant against such a knight as I? Who was the dolt who did not know that knights errant are exempt from all jurisdictional authority, or was unaware that their law is their sword, their edicts their courage, their statutes their will? Who was the imbecile, I say, who did not know that there is no patent of nobility with as many privileges and immunities as those acquired by a knight errant on the day he is dubbed a knight and dedicates himself to the rigorous practice of chivalry? What knight errant ever paid a tax, a duty, a queen’s levy, a tribute, a tariff, or a toll? What tailor ever received payment from him for the clothes he sewed? What castellan welcomed him to his castle and then asked him to pay the cost? What king has not sat him at his table? What damsel has not loved him and given herself over to his will and desire? And, finally, what knight errant ever was, is, or will be in the world who does not have the courage to single-handedly deliver four hundred blows to four hundred Brotherhoods if they presume to oppose him?”