Volume I (1605)

In which the captive recounts his life and adventures 223

“My family had its origins in the mountains of León, where nature was kinder and more generous than fortune, though in the extreme poverty of those villages my father was known as a rich man, and he truly would have been one if he had been as skilled in preserving his wealth as he was in spending it. This propensity for being generous and openhanded came from his having been a soldier in his youth, for soldiering is a school where the stingy man becomes liberal, and the liberal man becomes prodigal, and if there are any soldiers who are miserly, they are, like monsters, very rarely seen. My father exceeded the limits of generosity and bordered on being prodigal, something of little benefit to a man who is married and has children who will succeed to his name and position. My father had three sons, all of an age to choose a profession. Seeing, as he said, that he could not control his own nature, he decided to deprive himself of the means and cause of his being prodigal and a spendthrift by giving up his estate, without which Alexander himself would have seemed a miser. And so one day he called the three of us into a room where we could be alone, and he said something similar to what I will say now:

‘My sons, to say that I love you, it is enough to know and say that you are my children, and to understand that I do not love you, it is enough to know that I do not exercise control with regard to preserving your inheritance. So that you may know from now on that I love you as a father, and do not wish to destroy you as if I were your stepfather, I want to do something that I have been thinking about for a long time and, after mature consideration, have resolved to do. You are all of an age to choose a profession or, at least, to select an occupation that will bring you honor and profit when you are older. What I have decided is to divide my fortune into four parts: three I will give to you, each one receiving exactly the same share, and the fourth I will retain to keep me for the time it pleases heaven to grant me life. But after each of you has his share of the estate, I would like you to follow the path I indicate. There is a proverb in our Spain, one that I think is very true, as they all are, for they are brief maxims taken from long, judicious experience; the one I have in mind says: “The Church, the sea, or the royal house”; in other words, whoever wishes to be successful and wealthy should enter the Church, or go to sea as a merchant, or enter the service of kings in their courts, for, as they say: “Better the king’s crumbs than the noble lord’s favors.” I say this because I would like, and it is my desire, that one of you should pursue letters, another commerce, and the third should serve the king in war, for it is very difficult to enter his service at court, and although war does not provide many riches, it tends to bring great merit and fame. In a week’s time I shall give each of you his entire share in cash, down to the last ardite, as you will see. Tell me now if you wish to follow my opinion and advice in what I have proposed to you.’

And because I was the oldest he ordered me to respond, and after I had told him not to divest himself of his fortune but to spend as much of it as he wished, for we were young and could make one of our own, I concluded by saying I would do as he wished, and my desire was to follow the profession of arms and in that way serve God and my king. The second brother made a similar statement, but he chose to go to the Indies, using his portion to buy goods. The youngest, and, I believe, the wisest, said he wanted to enter the Church and complete the studies he had begun at Salamanca. When we had finished expressing our agreement and choosing our professions, my father embraced us all, and then, in as short a time as he had stated, he put into effect everything he had promised, and gave each of us his share, which, as I remember, amounted to three thousand gold ducados 224 (an uncle of ours bought the entire estate so that it would stay in the family, and paid for it in cash).

The three of us said goodbye to our good father on the same day, and on that day, thinking it was inhuman for my father to be left old and bereft of his fortune, I persuaded him to take two thousand of my three thousand ducados, because the remainder would be enough for me to acquire everything I needed to be a soldier. My two brothers, moved by my example, each gave him a thousand ducados, so that my father had four thousand in cash and another three thousand that was, apparently, the value of his portion of the estate, which he did not want to sell but kept as land. In short, with a good deal of emotion and many tears from everyone, we took our leave of him and the uncle I have mentioned, who asked us to inform them, whenever possible, about our affairs, whether prosperous or adverse. We promised we would, and they embraced us and gave us their blessing. One of us set out for Salamanca, the other left for Sevilla, and I took the road to Alicante, where I had heard that a Genoese ship was loading on wool, bound for Genoa.

It is twenty-two years since I left my father’s house, and in all that time, though I have written several letters, I have not heard anything from him or my brothers. I shall tell you briefly what happened to me in the course of this time. I embarked in Alicante, arrived safely in Genoa, went from there to Milan, where I purchased some arms and soldier’s clothing, and from there I decided to go to the Piedmont to enlist; I was already on the road to Alessandria della Paglia225 when I heard that the great Duke of Alba was on his way to Flanders.226 I changed my plans, went with him, served in his campaigns, witnessed the deaths of Counts Egmont and Horn,227 and rose to the rank of ensign under a famous captain from Guadalajara named Diego de Urbina;228 some time after my arrival in Flanders, we heard news of the alliance that His Holiness Pope Pius V, of happy memory, had made with Venice and Spain to fight our common enemy, the Turks; their fleet had recently conquered the famous island of Cyprus, which had been under the control of the Venetians: a lamentable and unfortunate loss. It was known that the commanding general of this alliance would be His Serene Highness Don Juan of Austria, the natural brother of our good king Don Felipe II. Reports of the great preparations for war that were being made moved my spirit and excited my desire to be part of the expected campaign, and although I had hopes, almost specific promises, that at the first opportunity I would be promoted to captain, I chose to leave it all and go to Italy. And it was my good fortune that Señor Don Juan of Austria had just arrived in Genoa, on his way to Naples to join the Venetian fleet, as he subsequently did in Messina.229

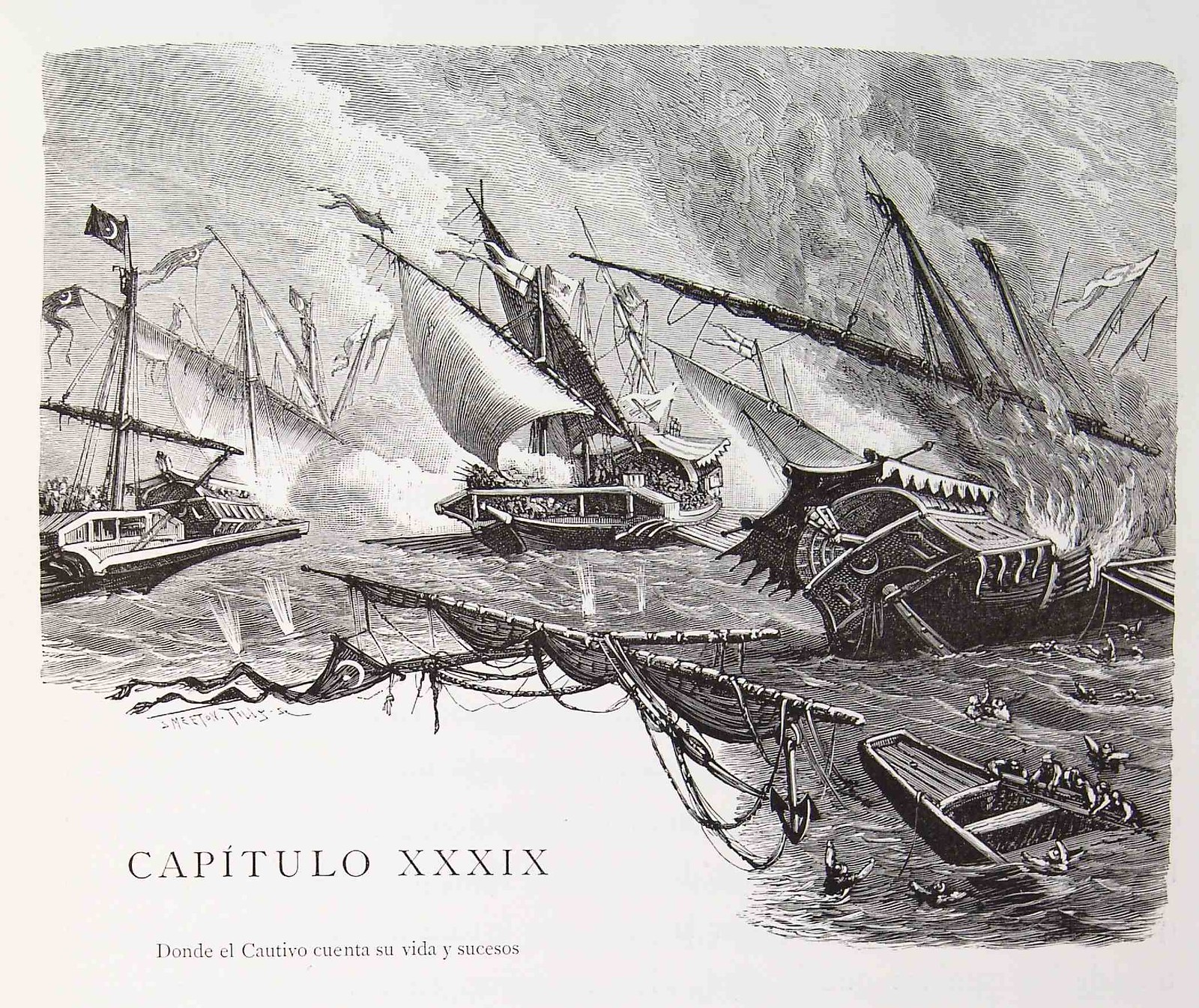

In short, I took part in that glorious battle, having achieved the rank of captain of infantry, an honor due more to my good luck than my merits. And that day, which was so fortunate for Christendom because that was when the world and all the nations realized their error in thinking that the Turks were invincible at sea, on that day, I say, when Ottoman pride and arrogance were shattered, among all the fortunate men who were there (for the Christians who died there were more fortunate than those left alive and victorious), I alone was unfortunate; for, contrary to what I might have expected in Roman times, instead of a naval crown230 I found myself on the night following so famous a day with chains on my feet and shackles on my hands. This is how it happened.

Uchalí,231 the king of Algiers, a daring and successful corsair, attacked and defeated the Maltese flagship, leaving only three knights alive, and they were badly wounded; the flagship of Juan Andrea,232 on which I and my company were sailing, came to her assistance, and doing what needed to be done on such an occasion, I jumped onto the enemy galley that then disengaged from our ship, which had grappled her, preventing my soldiers from following me; and so I found myself alone, surrounded by my enemies, who were so numerous I could not successfully resist them; finally, when I was covered with wounds, they took me prisoner. And, Señores, as you have probably heard, Uchalí escaped with his entire squadron, and I was his captive, the one sad man among so many who rejoiced, the one captive among so many who were free, because on that day fifteen thousand Christians at the oars of the Turkish fleet attained the liberty they longed for. I was taken to Constantinople, where the Great Turk Selim made my master the commanding admiral of the sea because he had done his duty in the battle, having brought back as a trophy of his valor the standard of the Order of Malta. The following year, 1572, I found myself at Navarino, rowing in the flagship that displayed the three lighthouses.233 There I saw and noted the chance that was lost to capture the entire Turkish fleet while it was still in port, because all its sailors and janissaries were certain they would be attacked in the harbor itself, and they had their clothing ready, and their pasamaques, which are their shoes, so that they could escape immediately by land and not wait to do battle: that was how fearful they had become of our fleet. But heaven ordained otherwise, not through the fault or negligence of the commander of our forces but because of the sins of Christendom, and because it is God’s will that there always will be scourges to punish us.

And so Uchalí withdrew to Modón, which is an island near Navarino, and putting his people ashore, he fortified the entrance to the port, and remained there until Señor Don Juan left. On this voyage the galley La Presa, whose captain was a son of the famous corsair called Barbarossa, was captured by the flagship of Naples, La Loba, under the command of that lightning bolt of war, that father to his soldiers, that victorious and never defeated Don Álvaro de Bazán, the Marquis of Santa Cruz. I want to be sure to tell you what happened in the capture of La Presa. The son of Barbarossa was so cruel, and treated his captives so badly, that as soon as those on the oars saw La Loba approaching and overtaking them, they all dropped their oars at the same time and seized the captain, who stood at his post and shouted at them to row faster, and they threw him from bench to bench, from stern to bow, biting him so many times that by the time he passed the mast his soul had passed on to hell, so cruel was his treatment of them, as I have said, and so great their hatred of him.

We returned to Constantinople, and the following year, 1573, we heard how Señor Don Juan had conquered Tunis, capturing that kingdom from the Turks and turning it over to Muley Hamet, thereby destroying the hopes of Muley Hamida, the cruelest and most valiant Moor in the world, that he would return to the throne.234 The Great Turk felt this loss very deeply, and, making use of the sagacity that all those of his house possess, he made peace with the Venetians, who desired it much more than he did, and the following year, which was 1574, he attacked the Goletta235 and the fort that Señor Don Juan had left partially constructed near Tunis. During all these battles I was at the oar, without any hope of freedom; at least, I did not hope to obtain it by means of a ransom, because I had decided not to write the news of my misfortune to my father. In the end, the Goletta was lost, and the fort as well, attacked by seventy-five thousand regular Turkish soldiers and more than four hundred thousand Moors and Arabs from the rest of Africa, and this vast army had so many weapons and supplies, and so many sappers, that they could have picked up earth and covered over the Goletta and the fort using only their bare hands.

The Goletta, until that time considered impregnable, was the first to fall, not because of any fault in its defenders, who did in its defense everything they should have done and all that they could do, but because experience showed how easily earthworks could be built in that desert sand, for at one time water was found at a depth of two spans, but the Turks did not find it at a depth of two varas; 236 and so, with countless sacks of sand they built earthworks so high that they rose above the walls of the fort, and their soldiers could fire down on the fort, and no one could stay there or help in its defense. It was the general opinion that our forces should not have closed themselves inside the Goletta but waited for the landing in open country, and those who say this speak from a distance and with little experience of this kind of warfare, because inside the Goletta and the fort there were barely seven thousand soldiers, and how could so small a number, no matter how brave, have gone into open country and defended the forts at the same time against the far larger numbers of the enemy? And how is it possible not to lose a fort when there is no relief, and it is surrounded by so many resolute enemies fighting on their own land? But it seemed to many, and it seemed to me, that it was a special grace and mercy that heaven conferred on Spain when it allowed the destruction of that breeding ground and shelter for wickedness, that voracious, gluttonous devourer of infinite amounts of money spent there to no avail, yet serving no other purpose than to preserve the happy memory of its having been captured by the invincible Carlos V, as if those stones were necessary to make his fame eternal, as it is now and forever will be. The fort was lost, too, but the Turks had to take it a span at a time, because the soldiers who defended it fought so valiantly and fiercely that they killed more than twenty-five thousand of the enemy in twenty-two general assaults. Three hundred of our soldiers survived, every one of them wounded when he was taken prisoner, a sure and certain sign of their tenacity and valor and of how well they defended and protected their positions. A small fortress or tower in the middle of the lagoon, commanded by Don Juan Zanoguera, a famous gentleman and soldier from Valencia, surrendered on advantageous terms. They captured Don Pedro Puertocarrero, the general in command of the Goletta, who did everything possible to defend the fortress and felt its loss so deeply that he died of sorrow on the road to Constantinople, where he was being taken as a prisoner. They also captured the general in command of the fort, whose name was Gabrio Cervellón, a Milanese gentleman who was a great engineer and a very courageous soldier.

Many notable men died in those two forts; one was Pagán Doria, a knight of the Order of St. John, an extremely generous man who showed great liberality to his brother, the famous Juan de Andrea Doria; what made his death even sadder was that he died at the hands of some Arabs whom he trusted when he saw that the fort was lost; they offered to take him, dressed as a Moor, to Tabarca, a small port where the Genoese who engage in the coral trade along these shores keep a house; these Arabs cut off his head and took it to the commander of the Turkish fleet, who confirmed for them our Spanish proverb: ‘For the treason we are grateful, though we find the traitor hateful.’ And so, they say, the commander ordered the two who brought him the present to be hanged because they did not bring the man to him alive. Among the Christians captured in the fort, there was one named Don Pedro de Aguilar, a native of Andalucía, though I do not know the town, who had been an ensign, and a soldier of great note and rare intelligence; he had a special gift for what they call poetry. I say this because his luck brought him to my galley, and my bench, to be the slave of my master, and before we left that port this gentleman composed two sonnets as epitaphs, one for the Goletta and the other for the fort. The truth is I must recite them, because I know them by heart, and I believe they will give you more pleasure than grief.”

When the captive named Don Pedro de Aguilar, Don Fernando looked at his companions, and all three of them smiled, and when the captive mentioned the sonnets, one of them said:

“Before your grace continues, I beg you to tell me what happened to this Don Pedro de Aguilar.”

“What I do know,” responded the captive, “is that after spending two years in Constantinople he escaped, disguised as an Albanian and in the company of a Greek spy, and I do not know if he obtained his freedom, though I believe he did, because a year later I saw the Greek in Constantinople but could not ask if they had been successful.”

“Well, they were,” responded the gentleman, “for Don Pedro is my brother, and he is now in our home, safe, rich, and married, with three children.”

“Thanks be to God,” said the captive, “for the mercies he has received; in my opinion, there is no joy on earth equal to that of regaining the freedom one has lost.”

“What is more,” replied the gentleman, “I know the sonnets my brother wrote.”

“Then your grace should recite them,” said the captive, “for I am certain you can say them better than I.”

“I would be happy to,” responded the gentleman. “The one to the Goletta says: