Volume I (1605)

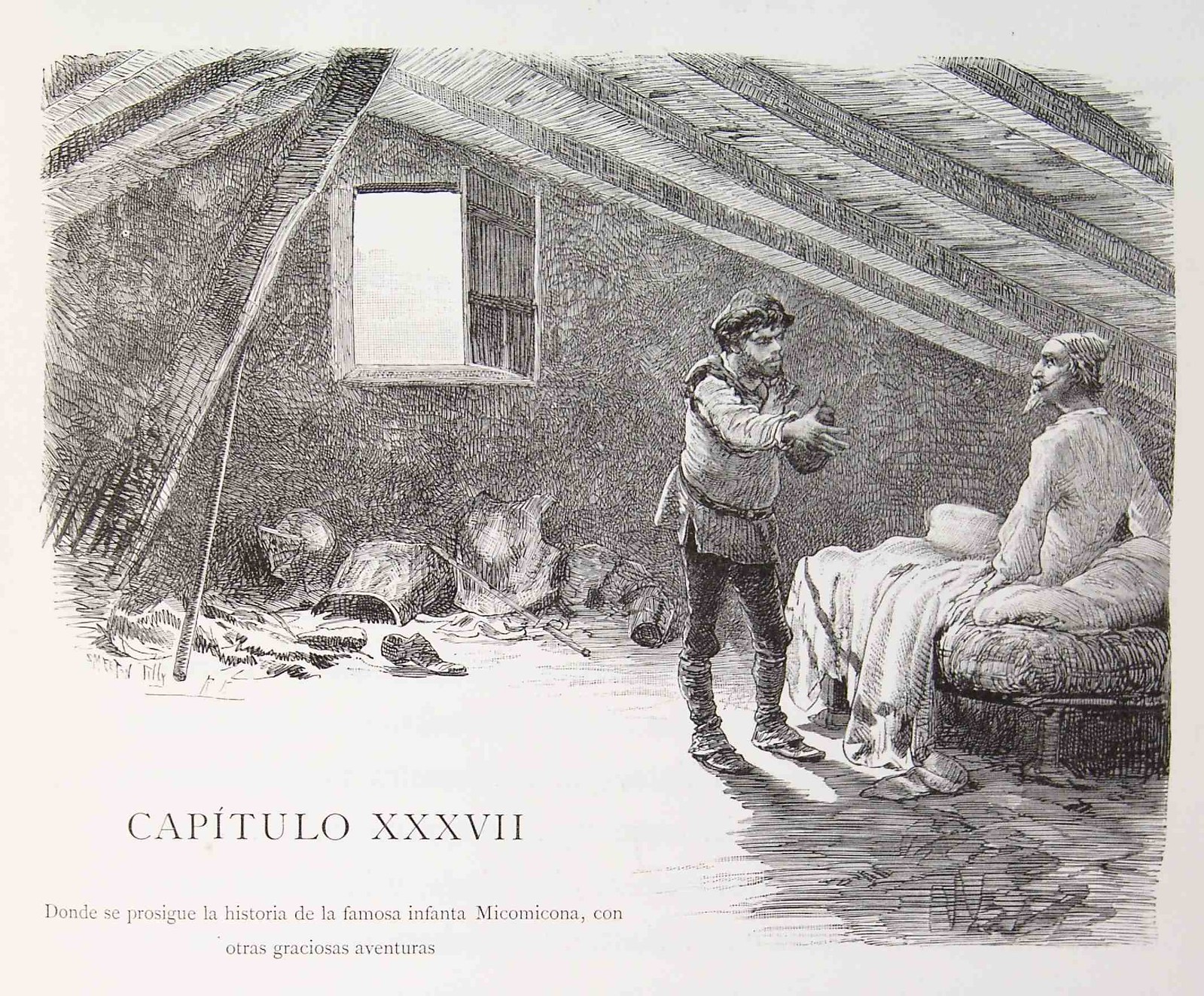

In which the history of the famous Princess Micomicona continues, along with other diverting adventures

Sancho listened to all of this with a very sorrowful spirit, for he saw that his hopes for a noble title were disappearing and going up in smoke, and that the lovely Princess Micomicona had turned into Dorotea, and the giant into Don Fernando, and that his master was in a deep, sound sleep, unaware of everything that had happened. Dorotea could not be certain she had not dreamed her great joy, Cardenio was in the same frame of mind, and Luscinda had the same thought. Don Fernando thanked heaven for its mercy in extricating him from the intricate labyrinth in which he had been on the verge of losing both his good name and his soul; in short, all the people in the inn were pleased, rejoicing at the happy outcome of such complex and desperate affairs.

The priest, a judicious man, put the final touch on everything by congratulating them all on the happiness each had achieved; but the one who was happiest and most joyful was the innkeeper’s wife, because Cardenio and the priest had promised to pay her for all the damage and all the costs she had incurred on Don Quixote’s account. Only Sancho, as we have said, was sorrowful, dejected, and sad, and so, with a melancholy expression, he went in to see his master, who had just awakened, and said:

“Your grace, Señor Sorrowful Face, can sleep all you want to now and not worry about killing any giant or returning the princess to her kingdom; it’s all over and done with.”

“I certainly believe that,” responded Don Quixote, “because with that giant I have had the most uncommon and furious battle I think I shall ever have in all my days, and with a single downstroke—smash!—I knocked his head to the ground, and so much blood poured out of him that it ran in streams along the floor as if it were water.”

“As if it were red wine, is what your grace should say,” responded Sancho, “because I want your grace to know, in case you don’t already, that the dead giant is a slashed wineskin, his blood, the six arrobas 217 of red wine contained in its belly, and the head you cut off is the whore who bore me, damn it all to hell!”

“Madman, what are you saying?” replied Don Quixote. “Have you lost your mind?”

“Get up, your grace,” said Sancho, “and you’ll see what you’ve won and what we have to pay, and you’ll see the queen transformed into an ordinary lady named Dorotea, and other changes that will amaze you, if you can see them for what they are.”

“I shall not marvel at any of it,” replied Don Quixote, “because, if you remember, the last time we were here I told you that all the things that occurred in this place were works of enchantment, and it would not surprise me if the same were true now.”

“I’d believe everything,” responded Sancho, “if my tossing in the blanket was that kind of thing, but it wasn’t, it was real and true, and I saw the innkeeper who’s here today holding a corner of the blanket and tossing me up to the sky with lots of enthusiasm and energy, and as much laughter as strength, and though I’m a simple man and a sinner, as far as I’m concerned, when you can recognize people there’s no enchantment at all, just a lot of bruising, and a lot of bad luck.”

“Well, then, God will remedy everything,” said Don Quixote. “Give me my clothes and let me go out there, for I wish to see the changes and transformations you have mentioned.”

Sancho handed him his clothes, and while he was dressing, the priest told Don Fernando and the others about the madness of Don Quixote, and the stratagem they had used to take him away from Peña Pobre, which is where he imagined he was, brought there by his lady’s scorn. He also related almost all the adventures that Sancho had recounted, which both astonished them and made them laugh, for they thought what everyone thought: it was the strangest kind of madness that had ever afflicted an irrational mind. The priest added that the fortunate change in Señora Dorotea’s circumstances prevented their plan from going forward, and it would be necessary to devise and invent another so they could take him home. Cardenio offered to continue what they had already begun and have Luscinda act the part played by Dorotea.

“No,” said Don Fernando, “by no means: I want Dorotea to go on with the fiction; this good gentleman’s village is probably not very far from here, and I would be happy if a cure could be found for him.”

“It’s no more than two days’ travel from here.”

“Even if it were more, I would be glad to make the trip for the sake of so good a work.”

At this moment Don Quixote came out, leaning on his branch, or lance, and wearing all his armor, the helmet of Mambrino, though battered, on his head, and his shield on his arm. Don Fernando and the others marveled at the strange appearance of Don Quixote, his dry, sallow face that was at least half a league long, his ill-matched weapons, and his solemn demeanor; they remained silent, waiting to see what he would say, and he, very gravely and serenely, turned his eyes toward the beautiful Dorotea, and said:

“I have been informed, O beauteous lady, by this my squire, that your greatness has been annihilated and your person undone, because from the queen and great lady you once were, you have turned into an ordinary damsel. If this has occurred by order of the necromancer king, your father, fearful I would not give you all the assistance you needed and deserved, then I say that he did not and does not know the half of what he should and is not well-versed in chivalric histories; if he had read them as attentively as I, and spent the same amount of time reading them as I, he would have found on every page how knights with less fame than mine had successfully concluded more difficult enterprises, finding it no great matter to kill some insignificant giant, no matter how arrogant; because not many hours ago I found myself with him and…I prefer to remain silent, because I do not wish anyone to say that I am lying, but Time, which reveals all things, will disclose this truth to us when we least expect it.”

“You found yourself with two wineskins, not with any giant,” said the innkeeper.

Don Fernando ordered him to be quiet and not, under any circumstances, to interrupt Don Quixote; and Don Quixote continued, saying:

“I say, then, O high and disinherited lady, that if for the reason I have mentioned your father has brought about this metamorphosis in your person, then you should place no trust in him because there is no danger on earth through which my sword does not clear a path; with it, in a few short days, I shall send the head of your enemy rolling on the ground and place on yours its rightful crown.”

Don Quixote stopped speaking and waited for the princess to respond, and she, knowing Don Fernando’s determination that the deception should continue until Don Quixote had been brought home, responded with grace and solemnity:

“Whoever told you, O valiant Knight of the Sorrowful Face, that I had changed and altered my being, did not tell you the truth, because I am today the same woman I was yesterday. It is true that some alteration has been caused in me by certain fortunate events that have given me the best I could desire, but I have not, for that reason, stopped being who I was before, and I still have the same intention I have always had to avail myself of the valor of your valiant and invenerable218 arm. Therefore, Señor, let your goodness restore honor to the father who sired me, and consider him a wise and prudent man, for with his knowledge he found so easy and true a way to remedy my misfortune that I believe, Señor, if it were not for you, I never would have enjoyed the good fortune I have now; what I say regarding this matter is true, as most of these gentlefolk here present can testify. All that remains is for us to start out tomorrow, because we could not travel very far today, and as for the other good outcomes that I hope to see, I shall leave them to God and to the valor of your heart.”

This is what the clever Dorotea said, and when Don Quixote heard it, he turned to Sancho, and showing signs of great anger, he said:

“I say to you now, wretched Sancho, that you are the greatest scoundrel in all of Spain. Tell me, you worthless thief, did you not just say to me that this princess had been transformed into a damsel named Dorotea, and that the head I believe I cut off a giant was the whore who bore you, and so much other foolishness that it caused me the greatest confusion I have ever felt in all the days of my life? I swear”—and he looked up to heaven and clenched his teeth—“that I am about to do so much damage to you that from this day forth it will put sense back into the heads of all the lying squires in the world who serve knights errant!”

“Your grace should calm down, Señor,” responded Sancho, “because it might be true I made a mistake about the change in the Señora Princess Micomicona, but as for the giant’s head, or, I should say, the slashed wineskins, and the blood being red wine, by God I’m not mistaken, because the wounded wineskins are there, at the head of your grace’s bed, and the red wine has formed a lake in the room; if you don’t believe me, the proof is in the pudding, I mean, you’ll have your proof when his grace the innkeeper asks you to pay damages for everything. As for the rest of it, my lady the queen being the same as she was before, that makes me happy because then I’ll get what’s due me, along with every mother’s son.”

“I tell you now, Sancho,” said Don Quixote, “that you are, forgive me, a dolt, and let us say no more. Enough.”

“Enough,” said Don Fernando, “let there be no more talk of this; since my lady the princess says she will set out tomorrow because it is too late today, let it be so, and we can spend tonight in pleasant conversation, and when day breaks we shall all accompany Señor Don Quixote, because we want to witness the valiant and extraordinary deeds he will perform in the course of this great enterprise that he has undertaken.”

“It is I who should serve and accompany you,” responded Don Quixote, “and I am most grateful for the favor you do me and the good opinion you have of me, which I shall strive to make true, or it will cost me my life, and even more, if anything can cost me more.”

Many words of praise and many offers of service were exchanged by Don Quixote and Don Fernando, but silence was imposed by a traveler who came into the inn just then; his clothing indicated that he was a Christian recently arrived from Moorish lands, for he was dressed in a short blue woolen tunic with half-sleeves and no collar, breeches of blue linen, and a cap of the same color; he wore ankle boots the color of dates, and a Moorish scimitar hung from a strap across his chest. Then a woman came in after him, riding on a donkey and dressed in the Moorish fashion, her face hidden by a veil; she wore a small brocade cap and a long cloak that covered her from her shoulders to her feet.

The man’s appearance was robust and attractive, his age a little over forty, his face rather dark, with a long mustache and a carefully trimmed beard; in short, his bearing revealed that if he had been well-dressed, he would have been deemed noble and highborn.

When he entered he asked for a room, and when he was told there was none in the inn, he seemed troubled; he approached the woman whose dress made her seem Moorish and lifted her down in his arms. Luscinda, Dorotea, the innkeeper’s wife, her daughter, and Maritornes, drawn by her clothing, which seemed strange to them, for they had not seen its like before, gathered around the Moorish woman, and Dorotea, who was always charming, courteous, and clever, thought that both she and the man who accompanied her were distressed by the lack of a room, and she said:

“Do not be troubled, Señora, at not finding suitable accommodation here, for it is almost never found in inns; even so, if you would like to stay with us”—and she pointed to Luscinda—“perhaps you will find a better welcome here than elsewhere on your journey.”

The veiled lady did not say anything in response, but she rose from the chair where she was sitting, crossed both hands on her bosom, inclined her head, and bowed to show her thanks. From her silence they imagined that she undoubtedly was a Moor and could not speak Christian. Just then the captive,219 who had been attending to other matters, approached, and seeing that all the women were standing around his companion, but that she did not respond to the statements directed to her, he said:

“Señoras, this maiden barely understands my language and does not know how to speak any other except the one spoken in her own country, and this is why she has not replied and will not reply to the questions you have asked her.”

“We have not asked her anything,” responded Luscinda, “but we have offered her our companionship for the night, and a place in the room where we will sleep, and as much comfort as it is possible to find here, for we desire and are bound to serve all strangers who need our help, especially if the one in need is a woman.”

“On her behalf and on mine,” responded the captive, “I kiss your hands, Señora, and I certainly esteem your offer as it deserves to be es-teemed; on an occasion such as this, and from persons such as yourselves, that merit is very high indeed.”

“Tell me, Señor,” said Dorotea, “is this lady a Christian or a Moor? Her dress and her silence make us think she is what we would rather she was not.”

“She is a Moor in her dress and body, but in her soul she is a devout Christian because she has a very strong desire to be one.”

“Then, she isn’t baptized?” replied Luscinda.

“We have not had the opportunity for that,” responded the captive, “since we left Algiers, her home and native land, and until now she has not been in mortal danger that would oblige her to be baptized without first knowing all the ceremonies required by our Holy Mother Church; but God willing, she will soon be baptized with all the decorum her station deserves, for it is higher than that indicated by her attire, or mine.”

With these words, he woke everyone’s desire to know who the Moorish lady was, and who the captive, but no one wished to ask any questions just then, since it was clearly time to allow them to rest rather than ask about their lives. Dorotea took the stranger by the hand, led her to a seat next to her own, and asked that she remove the veil. The Moorish lady looked at the captive, as if asking him to tell her what was being said and what she should do. He told her, in Arabic, that she was being asked to remove her veil and that she should do so, and she lifted her veil and revealed a face so beautiful that Dorotea thought her more beautiful than Luscinda, and Luscinda thought her more beautiful than Dorotea, and everyone present realized that if any beauty could equal that of those two women, it was the Moorish lady’s, and there were even some who thought hers superior in certain details. And since it is the prerogative and charm of beauty to win hearts and attract affection, everyone surrendered to the desire to serve and cherish the beautiful Moor.

Don Fernando asked the captive what her name was, and he replied that it was Lela 220 Zoraida, and as soon as the Moor heard this she understood what had been asked, and she hastened to say, with much distress but great charm:

“No! No Zoraida! María, María!” In this way she indicated that her name was María, not Zoraida.

These words, and the great emotion with which the Moorish lady said them, brought more than one tear to the eyes of some who were listening, especially the women, who are by nature tenderhearted and compassionate. Luscinda embraced her with a good deal of affection, saying:

“Yes, yes! María, María!”

To which the Moor responded:

“Yes, yes, María; Zoraida macange!”—a word that means no.

By this time night had fallen, and on the orders of those who had accompanied Don Fernando, the innkeeper had been diligent and careful in preparing the best supper he could. When it was time to eat, they all sat at a long refectory table, for there were no round or square ones in the inn, and they gave the principal seat at the head of the table to Don Quixote, although he tried to refuse it, and then he wanted Señora Micomicona at his side, for he was her protector. Then came Luscinda and Zoraida, and facing them Don Fernando and Cardenio, and then the captive and the other gentlemen, and on the ladies’ side, the priest and the barber. And in this manner they ate very happily, even more so when Don Quixote stopped eating, moved by a spirit similar to the one that had moved him to speak at length when he ate with the goatherds, and he began by saying:

“Truly, Señores, if one considers it carefully, great and wonderful are the things seen by those who profess the order of knight errantry. For who in this world, coming through the door of this castle and seeing us as we appear now, would judge and believe that we are who we are? Who would say that this lady at my side is the great queen we all know she is, and that I am the Knight of the Sorrowful Face whose name is on the lips of fame? There can be no doubt that this art and profession exceeds all others invented by men, for the more dangerous something is, the more it should be esteemed. Away with those who say that letters are superior to arms,221 for I shall tell them, whoever they may be, that they do not know what they are saying. The reason usually given by these people, and the one on which they rely, is that the works of the spirit are greater than those of the body, and that arms are professed by the body alone, as if this profession were the work of laborers, for which one needs nothing more than strength, or as if in the profession we call arms, those of us who practice it do not perform acts of fortitude that demand great intelligence to succeed, or as if the courage of a warrior who leads an army or defends a city under siege does not make use of his spirit as well as his body. If you do not agree, consider that knowing the enemy’s intentions, surmising his plans and stratagems, foreseeing difficulties, preventing harm: all of these are actions of mind in which the body plays no part at all. If it is true that arms require spirit, as do letters, let us now see which of the two spirits, that of the lettered man or that of the warrior, is more active; this can be known by the purpose and aim of each, for an intention must be more highly esteemed if it has as its object a nobler end.

The purpose and aim of letters—and I do not speak now of divine letters, whose purpose is to bring and guide souls to heaven; so eternal an end cannot be equaled by any other—I am speaking of human letters, whose purpose is to maintain distributive justice, and give each man what is his, and make certain that good laws are obeyed. A purpose, certainly, that is generous and high and worthy of great praise, but not so meritorious as arms, whose purpose and objective is peace, which is the greatest good that men can desire in this life. And so, the first good news that the world and men received was brought by angels on the night that was our day, when they sang in the air: ‘Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, goodwill toward men,’ and the greeting that the best teacher on earth and in heaven taught His disciples and followers was that when they entered a house they should say: ‘Peace be in this house,’ and often He said to them: ‘My peace I give unto you; my peace I leave with you; peace be with you,’ as if it were a precious jewel when given and offered by that hand, a jewel without which there can be no good on earth or in heaven. This peace is the true purpose of war, and saying arms is the same as saying war. Accepting it is true that the purpose of war is peace, which is greater than the purpose of letters, let us turn now to the physical hardships of the lettered man and those of the man who professes arms, and see which are greater.”

In this manner, and with these rational arguments, Don Quixote continued his discourse, and no one listening to him at that moment could think of him as a madman; rather, since most were gentlemen engaged in the practice of arms, they were very pleased to listen, and he went on, saying:

“I say, then, that the hardships of the student are these: principally poverty, not because they all are poor, but to make this case as extreme as possible, and having said that he suffers poverty, it seems to me that there is nothing more to say about his bad luck, because the man who is poor has nothing that is good. This poverty is suffered in its various forms, in hunger, cold, and nakedness, and sometimes all of them together; even so, his poverty is not so great that he does not eat, although the meal may be a little later than usual, or may be the leftovers of the rich, and his greatest misery is what students call among themselves going for soup; 222 and they do not lack someone else’s brazier or hearth, and if it does not warm them, at least it lessens the cold, and at night they sleep under a blanket. I do not wish to discuss other trivial matters, such as a lack of shirts and a shortage of shoes, and clothing that is scant and threadbare, or the relish with which they gorge themselves when fortune offers them a feast. Along this rough and difficult road that I have described, they stumble and fall, pick themselves up and fall again, until they reach the academic title they desire; once this is acquired and they have passed through these shoals, these Scyllas and Charybdises, as if carried on the wings of good fortune, we have seen many who command and govern the world from a chair, their hunger turned into a full belly, their cold into comfort, their nakedness into finery, and their straw mat into linen and damask sheets, the just reward for their virtue. But their hardships, measured against and compared to those of a soldier and warrior, fall far behind, as I shall relate to you now.”