Volume II (1615)

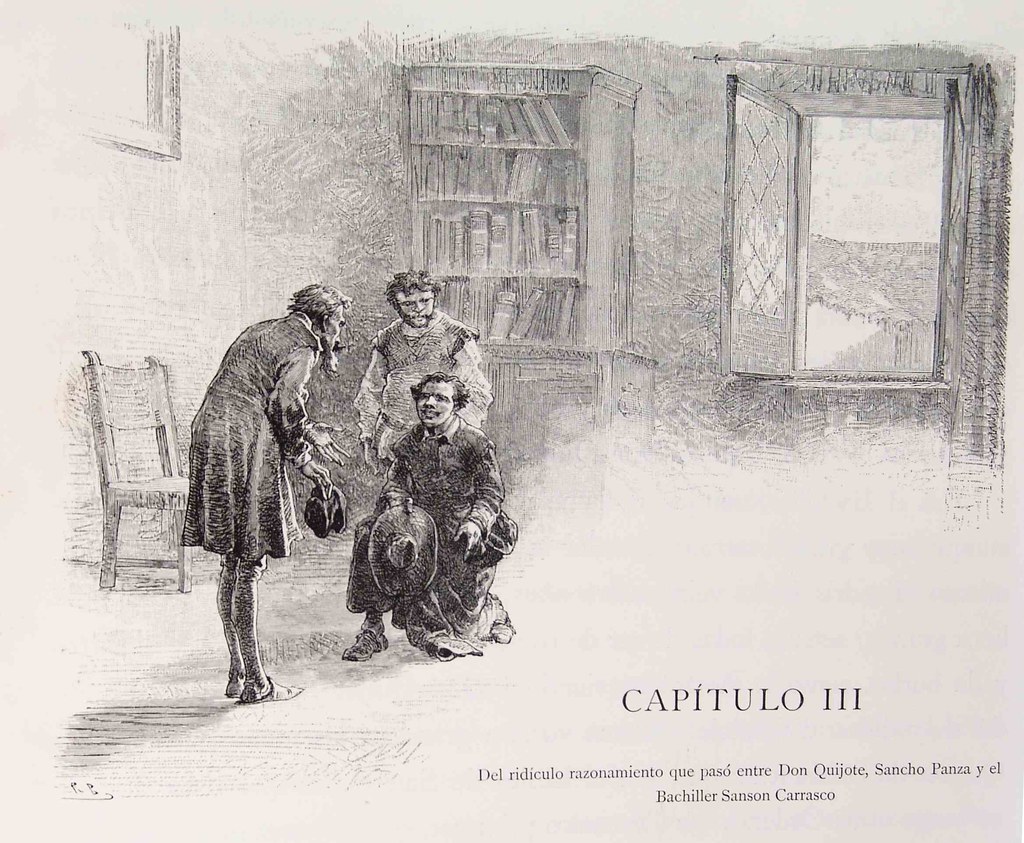

Regarding the comical discussion held by Don Quixote, Sancho Panza, and Bachelor Sansón Carrasco

Don Quixote was extremely thoughtful as he awaited Bachelor Carrasco, from whom he hoped to hear the news about himself that had been put into a book, as Sancho had said, though he could not persuade himself that such a history existed, for the blood of the enemies he had slain was not yet dry on the blade of his sword and his chivalric exploits were already in print. Even so, he imagined that some wise man, either a friend or an enemy, by the arts of enchantment had printed them: if a friend, in order to elevate them and raise them above the most famous deeds of any knight errant; if an enemy, to annihilate them and place them lower than the basest acts ever attributed to the basest squire, al-though—he said to himself—the acts of squires were never written down; if such a history did exist, because it was about a knight errant it would necessarily be grandiloquent, noble, distinguished, magnificent, and true.

This gave him some consolation, but it made him disconsolate to think that its author was a Moor, as suggested by the name Cide, and one could not expect truth from the Moors, because all of them are tricksters, liars, and swindlers. He feared his love had been treated with an indecency that would redound to the harm and detriment of the modesty of his lady Dulcinea of Toboso; he earnestly hoped there had been a declaration of the fidelity and decorum with which he had always behaved toward her, disdaining queens, empresses, and maidens of all ranks and keeping at bay the force of his natural passions; and so, rapt and enrapt in these and many other thoughts, he was found by Sancho and Carrasco, whom Don Quixote received with great courtesy.

The bachelor, though his name was Sansón,323 was not particularly large, but he was immensely sly; his color was pale, but his intelligence was very bright; he was about twenty-four years old, with a round face, a snub nose, and a large mouth, all signs of a mischievous nature and a fondness for tricks and jokes, which he displayed when, upon seeing Don Quixote, he kneeled before him and said:

“Your magnificence, Señor Don Quixote of La Mancha, give me your hands, for by the habit of St. Peter that I wear,324 though I have taken only the first four orders, your grace is one of the most famous knights errant there ever was, or will be, anywhere on this round earth. Blessings on Cide Hamete Benengeli, who wrote the history of your great deeds, and double blessings on the inquisitive man who had it translated from Arabic into our vernacular Castilian, for the universal entertainment of all people.”

Don Quixote had him stand, and he said:

“So then, is it true that my history exists, and that it was composed by a wise Moor?”

“It is so true, Señor,” said Sansón, “that I believe there are more than twelve thousand copies of this history in print today; if you do not think so, let Portugal, Barcelona, and Valencia tell you so, for they were printed there; there is even a rumor that it is being printed in Antwerp, and it is evident to me that every nation or language will have its translation of the book.”325

“One of the things,” said Don Quixote, “that must give the greatest contentment to a virtuous and eminent man is to see, while he is still alive, his good name printed and published in the languages of different peoples. I said good name, for if it were the opposite, no death could be its equal.”

“In the matter of a good reputation and a good name,” said the bachelor, “your grace alone triumphs over all other knights errant, for the Moor in his language and the Christian in his were careful to depict very vividly the gallantry of your grace, your great courage in confronting danger, your patience in adversity, your forbearance in the face of misfortunes and wounds, the virtue and modesty of the Platonic love of your grace and my lady Doña Dulcinea of Toboso.”

“Never,” said Sancho Panza, “have I heard my lady Dulcinea called Doña, just Señora Dulcinea of Toboso, and that’s where the history’s wrong.”

“That is not an important objection,” responded Carrasco.

“No, of course not,” responded Don Quixote, “but tell me, Señor Bachelor: which deeds of mine are praised the most in this history?”

“In that regard,” responded the bachelor, “there are different opinions, just as there are different tastes: some prefer the adventure of the windmills, which your grace thought were Briareuses and giants; others, that of the waterwheel; one man favors the description of the two armies that turned out to be two flocks of sheeps; the other praises the adventure of the body that was being carried to Segovia for burial; one says that the adventure of the galley slaves is superior to all the rest; another, that none equals that of the two gigantic Benedictines and the dispute with the valiant Basque.”

“Tell me, Señor Bachelor,” said Sancho, “is the adventure of the Yanguesans mentioned, when our good Rocinante took a notion to ask for the moon?”

“The wise man,” responded Sansón, “left nothing in the inkwell; he says everything and takes note of everything, even the capering that our good Sancho did in the blanket.”

“In the blanket I wasn’t capering,” responded Sancho, “but I was in the air, and more than I would have liked.”

“It seems to me,” said Don Quixote, “there is no human history in the world that does not have its ups and downs, especially those that deal with chivalry; they cannot be filled with nothing but successful exploits.”

“Even so,” responded the bachelor, “some people who have read the history say they would have been pleased if its authors had forgotten about some of the infinite beatings given to Señor Don Quixote in various encounters.”

“That’s where the truth of the history comes in,” said Sancho.

“They also could have kept quiet about them for the sake of fairness,” said Don Quixote, “because the actions that do not change or alter the truth of the history do not need to be written if they belittle the hero. By my faith, Aeneas was not as pious as Virgil depicts him, or Ulysses as prudent as Homer describes him.”

“That is true,” replied Sansón, “but it is one thing to write as a poet and another to write as a historian: the poet can recount or sing about things not as they were, but as they should have been, and the historian must write about them not as they should have been, but as they were, without adding or subtracting anything from the truth.”

“Well, if this Moorish gentleman is interested in telling the truth,” said Sancho, “then among all the beatings my master received, you’re bound to find mine, because they never took the measure of his grace’s shoulders without taking it for my whole body; but there’s no reason for me to be surprised, because as my master himself says, all the members must share in the head’s pain.”

“You are very crafty, Sancho,” responded Don Quixote. “By my faith, you have no lack of memory when you want to remember.”

“When I would like to forget the beatings I’ve gotten,” said Sancho, “the welts won’t let me, because they’re still fresh on my ribs.”

“Be quiet, Sancho,” said Don Quixote, “and do not interrupt the bachelor, whom I implore to continue telling me what is said about me in this history.”

“And about me,” said Sancho. “They also say I’m one of the principal presonages in it.”

“Personages, not presonages, Sancho my friend,” said Sansón.

“Another one who corrects my vocablery?” said Sancho. “Well, both of you keep it up and we’ll never finish.”

“As God is my witness, Sancho,” responded the bachelor, “you are the second person in the history, and there are some who would rather hear you talk than the cleverest person in it, though there are also some who say you were much too credulous when you believed that the governorship of the ínsula offered to you by Señor Don Quixote, here present, could be true.”

“The sun has not yet gone down,” said Don Quixote, “and as Sancho grows older, with the experience granted by his years he will be more skilled and more capable of being a governor than he is now.”

“By God, Señor,” said Sancho, “the island that I can’t govern at the age I am now I won’t be able to govern if I get to be as old as Methuselah. The trouble is that this ínsula is hidden someplace, I don’t know where, it’s not that I don’t have the good sense to govern it.”

“Trust in God, Sancho,” said Don Quixote, “that everything will turn out well and perhaps even better than you expect; not a leaf quivers on a tree unless God wills it.”

“That’s true,” said Sansón. “If it is God’s will, Sancho will have a thousand islands to govern, not just one.”

“I have seen some governors,” said Sancho, “who, in my opinion, don’t come up to the sole of my shoe, and even so they’re called lordship and are served their food on silver.”

“They aren’t governors of ínsulas,” replied Sansón, “but of other, more tractable realms; those who govern ínsulas have to know grammar at the very least.”

“I can accept the gram all right,” said Sancho, “but the mar I won’t go near because I don’t understand it. But leaving the question of my being a governor in the hands of God, and may He place me wherever He chooses, I say, Señor Bachelor Sansón Carrasco, that it makes me very happy that the author of the history has spoken about me in such a way that the things said about me do not give offense; for by my faith as a good squire, if things had been said about me that did not suit an Old Christian, which is what I am, even the deaf would have heard us.”

“That would be performing miracles,” responded Sansón.

“Miracles or no miracles,” said Sancho, “each man should be careful how he talks or writes about people and not put down willy-nilly the first thing that comes into his head.”

“One of the objections people make to the history,” said the bachelor, “is that its author put into it a novel called The Man Who Was Recklessly Curious, not because it is a bad novel or badly told, but because it is out of place and has nothing to do with the history of his grace Señor Don Quixote.”

“I’ll bet,” replied Sancho, “that the dogson mixed up apples and oranges.”

“Now I say,” said Don Quixote, “that the author of my history was no wise man but an ignorant gossip-monger who, without rhyme or reason, began to write, not caring how it turned out, just like Orbaneja, the painter of Úbeda, who, when asked what he was painting, replied: ‘Whatever comes out.’ Perhaps he painted a rooster in such a fashion and so unrealistically that he had to write beside it, in capital letters: ‘This is a rooster.’ And that must be how my history is: a commentary will be necessary in order to understand it.”

“Not at all,” responded Sansón, “because it is so clear that there is nothing in it to cause difficulty: children look at it, youths read it, men understand it, the old celebrate it, and, in short, it is so popular and so widely read and so well-known by every kind of person that as soon as people see a skinny old nag they say: ‘There goes Rocinante.’ And those who have been fondest of reading it are the pages. There is no lord’s antechamber where one does not find a copy of Don Quixote: as soon as it is put down it is picked up again; some rush at it, and others ask for it. In short, this history is the most enjoyable and least harmful entertainment ever seen, because nowhere in it can one find even the semblance of an untruthful word or a less than Catholic thought.”

“Writing in any other fashion,” said Don Quixote, “would mean not writing truths, but lies, and historians who make use of lies ought to be burned, like those who make counterfeit money; I do not know what moved the author to resort to other people’s novels and stories when there was so much to write about mine: no doubt he must have been guided by the proverb that says: ‘Straw or hay, it’s the same either way.’ For the truth is that if he had concerned himself only with my thoughts, my sighs, my tears, my virtuous desires, and my brave deeds, he could have had a volume larger than, or just as large as, the collected works of EI Tostado.326 In fact, as far as I can tell, Señor Bachelor, in order to write histories and books of any kind, one must have great judgment and mature understanding. To say witty things and to write cleverly requires great intelligence: the most perceptive character in a play is the fool, because the man who wishes to seem simple cannot possibly be a simpleton. History is like a sacred thing; it must be truthful, and wherever truth is, there God is; but despite this, there are some who write and toss off books as if they were fritters.”

“There is no book so bad,” said the bachelor, “that it does not have something good in it.”

“There is no doubt about that,” replied Don Quixote, “but it often happens that those who had deservedly won and achieved great fame because of their writings lost their fame, or saw it diminished, when they had their works printed.”

“The reason for that,” said Sansón, “is that since printed works are looked at slowly, their faults are easily seen, and the greater the fame of their authors, the more closely they are scrutinized. Men who are famous for their talent, great poets, eminent historians, are always, or almost always, envied by those whose particular pleasure and entertainment is judging other people’s writings without ever having brought anything of their own into the light of day.”

“That is not surprising,” said Don Quixote, “for there are many theologians who are not good in the pulpit but are excellent at recognizing the lacks or excesses of those who preach.”

“All this is true, Señor Don Quixote,” said Carrasco, “but I should like those censurers to be more merciful and less severe and not pay so much attention to the motes in the bright sun of the work they criticize, for if aliquando bonus dormitat Homerus, 327 they should consider how often he was awake to give a brilliant light to his work with the least amount of shadow possible; and it well may be that what seem defects to them are birthmarks that often increase the beauty of the face where they appear; and so I say that whoever prints a book exposes himself to great danger, since it is utterly impossible to write in a way that will satisfy and please everyone who reads it.”

“The one that tells about me,” said Don Quixote, “must have pleased very few.”

“Just the opposite is true; since stultorum infinitus est numerus, 328 an infinite number of people have enjoyed the history, though some have found fault and failure in the author’s memory, because he forgets to tell who the thief was who stole Sancho’s donkey, for it is never stated and can only be inferred from the writing that it was stolen, and soon after that we see Sancho riding on that same donkey and don’t know how it reappears. They also say that he forgot to put in what Sancho did with the hundred escudos he found in the traveling case in the Sierra Morena, for it is never mentioned again, and there are many who wish to know what he did with them, or how he spent them, for that is one of the substantive points of error in the work.”

Sancho responded:

“I, Señor Sansón, am in no condition now to give accounts or accountings; my stomach has begun to flag, and if I don’t restore it with a couple of swallows of mellow wine, I’ll be nothing but skin and bone. I keep some at home; my missus is waiting for me; when I finish eating I’ll come back and satisfy your grace and anybody else who wants to ask questions about the loss of my donkey or the hundred escudos.”

And without waiting for a reply or saying another word, he left for his house.

Don Quixote asked and invited the bachelor to stay and eat with him. The bachelor accepted: he stayed, a couple of squab were added to the ordinary meal, chivalry was discussed at the table, Carrasco humored the knight, the banquet ended, they took a siesta, Sancho returned, and their earlier conversation was resumed.