Volume II (1615)

Which deals with matters related to this history and to no other

The duke and duchess resolved that Don Quixote’s challenge to their vassal for the reason already recounted should go forward, and since the young man was in Flanders, where he had fled so as not to have Doña Rodríguez for a mother-in-law, they ordered a Gascon footman named Tosilos to appear in his place, first instructing him very carefully in everything he had to do.

Two days later, the duke told Don Quixote that in four days his opponent would come to present himself in the field, armed as a knight, to maintain that the maiden was lying through some, if not all, of her teeth559 if she affirmed he had given her a promise of marriage. Don Quixote was very happy to hear the news, and he promised himself to perform miracles in this matter, and he considered it very fortunate that an opportunity had presented itself that would allow the duke and duchess to see the extent of the valor of his mighty arm; and so, with joy and delight, he waited for the four days to pass, although if reckoned by his desire, they had become four hundred centuries.

Let us allow them to pass, as we have allowed other things to pass, and accompany Sancho, who was both happy and sad as he came riding on the gray to find his master, whose companionship pleased him more than being governor of all the ínsulas in the world.

He had not gone very far from the ínsula of his governorship—he had never bothered to find out if it was an island, city, town, or village that he was governing—when he saw coming toward him along the road six pilgrims with their staffs,560 the kind of foreign pilgrims who beg for alms by singing, and as they approached him they arranged themselves in a row, lifted their voices, and began to sing in their own language, which Sancho could not understand except for the one word alms, which was clearly pronounced, and then he understood that in their song they were asking for alms; since he, as Cide Hamete says, was excessively charitable, he took from his saddlebags his provisions of half a loaf of bread and half a cheese, which he offered to the pilgrims, indicating by signs that he had nothing else to give. They accepted the food very gladly and said:

“Geld! Geld!” 561

“I don’t understand,” responded Sancho, “what you’re asking of me, good people.”

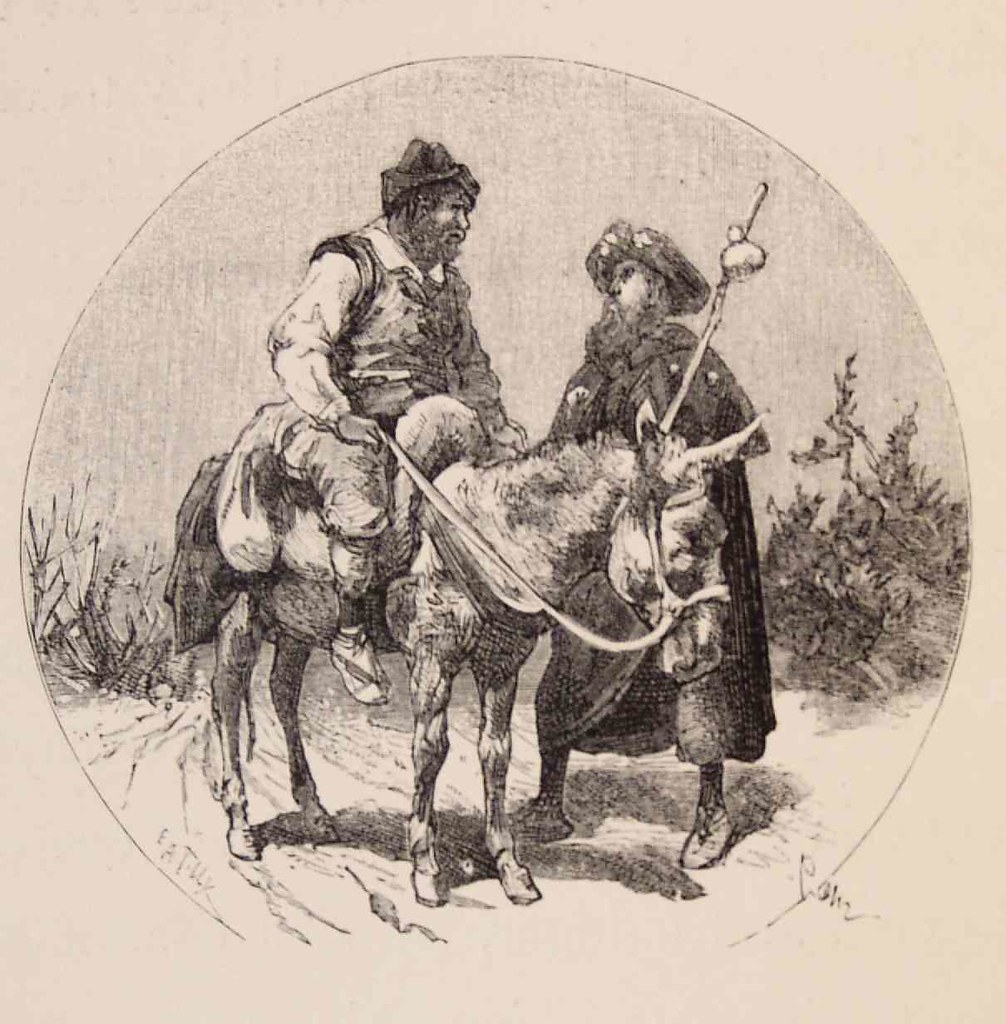

Then one of them took a purse from his shirt and showed it to Sancho, who then understood that they were asking for money, and he, placing his thumb on his throat and extending his hand upward, gave them to understand that he did not have any money at all; and spurring the donkey, he broke through the line, and as he passed, a pilgrim who had been looking at him very carefully rushed toward him, threw his arms around his waist, and said in a loud and very Castilian voice:

“God save me! What do I see? Is it possible that I have my arms around my dear friend and good neighbor Sancho Panza? I do, no doubt about it, because I’m not asleep or drunk now.”

Sancho was amazed to hear himself called by name and to find himself embraced by a foreign pilgrim, and he looked at him very carefully, not saying a word, but did not recognize him; the pilgrim, however, seeing his bewilderment, said:

“How is it possible, my brother Sancho Panza, that you don’t know your neighbor Ricote the Morisco,562 a shopkeeper in your village?”

Then Sancho looked at him even more closely, and began to recognize his face, and finally knew exactly who he was, and without dismounting, Sancho threw his arms around the man’s neck and said:

“Who the devil could recognize you, Ricote, in the ridiculous disguise you’re wearing? Tell me, who turned you into a foreigner, and why did you risk coming back to Spain? It’ll be very dangerous for you if they catch you and recognize you.”

“If you don’t give me away, Sancho,” responded the pilgrim, “I’m sure nobody will know me in these clothes; let’s move off the road to that grove of poplars where my companions want to eat and rest, and you can eat with them, for they’re very peaceable people. I’ll have a chance to tell you what happened to me after I left our village, obeying His Majesty’s proclamation that threatened the unfortunate members of my race so severely, as you must have heard.”563

Sancho agreed, and after Ricote spoke to the other pilgrims, they set out for the grove of poplars that could be seen at some distance from the king’s highway. They threw down their staffs, took off their hooded cloaks or capes, and remained in their shirtsleeves; they were all young and good-looking except for Ricote, who was a man well on in years. All of them carried traveling bags, and all of these, it seemed, were well-provisioned, at least with things that call up and summon a thirst from two leagues away.

They stretched out on the ground, and with the grass as their tablecloth, they set out bread, salt, knives, nuts, pieces of cheese, and bare ham-bones that could not be gnawed but could still be sucked. They also set out a black food called cabial 564 that is made of fish eggs and is a great awakener of thirst. There was no lack of olives, dried without any brine but good-tasting and flavorful. What stood out most on the field of that banquet, however, were six wineskins, for each of them took one out of his bag; even the good Ricote, transformed from a Morisco into a German or Teuton, took out his own wineskin, comparable in size to the other five.

They began to eat with great pleasure, savoring each mouthful slowly, just a little of each thing, which they picked up with the tip of a knife, and then all at once, and all at the same time, they raised their arms and the wineskins into the air, their mouths pressed against the mouths of the wineskins and their eyes fixed on heaven, as if they were taking aim; they stayed this way for a long time, emptying the innermost contents of the skins into their stomachs, and moving their heads from one side to the other, signs that attested to the pleasure they were receiving.

Sancho watched everything, and not one thing caused him sorrow;565 rather, in order to comply with a proverb that he knew very well—“When in Rome, do as the Romans do”—he asked Ricote for his wineskin and took aim along with the rest and with no less pleasure than they enjoyed.

The skins were tilted four times, but a fifth time was not possible because they were now as dry and parched as esparto grass, something that withered the joy the pilgrims had shown so far. From time to time one of them would take Sancho’s right hand in his and say:

“Español y tudesqui, tuto uno: bon compaño!”

And Sancho would respond:

“Bon compaño, jura Di!”

And he burst into laughter that lasted for an hour, and then he did not remember anything that had happened to him in his governorship; for during the time and period when one eats and drinks, cares tend to be of little importance. Finally, the end of the wine was the beginning of a fatigue that overcame everyone and left them asleep on their tables and cloths; only Ricote and Sancho were awake, because they had eaten more and drunk less than the others; Ricote moved away with Sancho to sit at the foot of a beech tree, leaving the pilgrims deep in their sweet sleep, and Ricote, without slipping at all into his Moorish language, said these words in pure Castilian:

“You know very well, O Sancho Panza, my neighbor and friend, how the proclamation and edict that His Majesty issued against those of my race brought terror and fear to all of us; at least, I was so affected, I think that even before the time granted to us for leaving Spain had expired, I was already imagining that the harsh penalty had been inflicted on me and my children. And so I arranged, as a prudent man, I think, and as one who knows that by a certain date the house where he lives will be taken away and he’ll need to have another one to move into, I arranged, as I said, to leave the village alone, without my family, and find a place where I could take them in comfort and without the haste with which others were leaving; because I saw clearly, as did all our elders, that those proclamations were not mere threats, as some were saying, but real laws that would be put into effect at the appointed time; I was forced to believe this truth because I knew the hateful and foolish intentions of our people, and they were such that it seems to me it was divine inspiration that moved His Majesty to put into effect so noble a resolution, not because all of us were guilty, for some were firm and true Christians, though these were so few they could not oppose those who were not, but because it is not a good idea to nurture a snake in your bosom or shelter enemies in your house.

In short, it was just and reasonable for us to be chastised with the punishment of exile: lenient and mild, according to some, but for us it was the most terrible one we could have received. No matter where we are we weep for Spain, for, after all, we were born here and it is our native country; nowhere do we find the haven our misfortune longs for, and in Barbary and all the places in Africa where we hoped to be received, welcomed, and taken in, that is where they most offend and mistreat us. We did not know our good fortune until we lost it, and the greatest desire in almost all of us is to return to Spain; most of those, and there are many of them, who know the language as well as I do, abandon their wives and children and return, so great is the love they have for Spain; and now I know and feel the truth of the saying that it is sweet to love one’s country.

As I was saying, I left our village, went to France, and though they made us welcome there, I wanted to see everything. I traveled to Italy, and came to Germany, and there it seemed to me I could live in greater freedom because the inhabitants don’t worry about subtleties: each man lives as he chooses, because in most places there is freedom of conscience. I took a house in a village near Augsburg; I joined these pilgrims, for many travel to Spain every year to visit the shrines, which they think of as their Indies: as sure profit and certain gain. They travel through most of the country, and they leave every town well-fed and well-drunk, as they say, and with at least a real in money, and at the end of the trip they have more than a hundred escudos left over, which they change into gold coins and hide in the hollows of their staffs, or under the patches on their cloaks, or wherever else they can, and they take them out of this kingdom and into their own countries in spite of the guards at the posts and ports where there are inspections.

Now, Sancho, my intention is to take out the treasure I buried here, and since it’s outside the village, I’ll be able to do it without danger, and then I’ll write to my daughter and wife, or leave from Valencia and go to Algiers, where I know they are, and find a way to take them to a French port, and from there to Germany, where we’ll wait for whatever God has in store for us; in short, Sancho, I know for a fact that my daughter, Ricota, and my wife, Francisca Ricota, are true Catholic Christians, and though I’m less of one, I’m still more Christian than Moor, and I always pray that God will open the eyes of my understanding and let me know how I must serve Him. What amazes me is not knowing why my wife and daughter went to Barbary instead of France, where they could have lived as Christians.”

To which Sancho responded:

“Look, Ricote, that probably wasn’t their decision, because Juan Tiopieyo, your wife’s brother, left with them, and since he’s probably a shrewd Moor, he took them to the place he thought best, and I can tell you something else, too: I think it’s useless for you to look for what you buried, because we heard that the pearls and gold coins your brother-in-law and your wife were carrying were taken at inspection.”

“That might be, Sancho,” replied Ricote, “but I know they didn’t touch what I hid away: I didn’t tell them where it was because I feared some calamity; and so, Sancho, if you want to come with me and help me to dig it up and hide it, I’ll give you two hundred escudos, and with that you can meet all your needs, for you know that I know you have a good many of them.”

“I’d do it,” responded Sancho, “but I’m not a greedy man, because just this morning I left a post where I could have had gold walls in my house and been eating off silver plates in six months’ time; and for this reason, and because I think it would be treason against my king if I helped his enemies, I wouldn’t go with you even if you gave me four hundred escudos in cash right here and now instead of promising me two hundred later.”

“And what post is it that you’ve left, Sancho?” asked Ricote.

“I’ve left the governorship of an ínsula,” responded Sancho, “one so good that, by my faith, you’d have a hard time finding another like it.”

“And where is this ínsula?” asked Ricote.

“Where?” responded Sancho. “Two leagues from here, and it’s called Ínsula Barataria.”

“That’s amazing, Sancho,” said Ricote. “Ínsulas are in the ocean; there are no ínsulas on terra firma.”

“What do you mean?” replied Sancho. “I tell you, Ricote my friend, I left there this morning, and yesterday I was there governing to my heart’s content, like an archer;566 but even so, I left it because the post of governor seems like a dangerous one to me.”

“What did you get from your governorship?” asked Ricote.

“I got,” responded Sancho, “the lesson that I’m not good for governing unless it’s a herd of livestock, and that the riches you can gain in governorships come at the cost of your rest and your sleep and even your food, because on ínsulas the governors have to eat very little, especially if they have doctors who are looking out for their health.”

“I don’t understand you, Sancho,” said Ricote, “but it seems to me that everything you’re saying is nonsense; who would give you ínsulas to govern? Was there a lack of men in the world more competent than you to be governors? Really, Sancho, come to your senses and decide if you want to come with me, as I said, and help me take out the treasure I hid; the truth is there’s so much it can be called a treasure, and I’ll give you enough to live on, as I said.”

“I already told you, Ricote,” replied Sancho, “that I don’t want to; be satisfied that I won’t betray you, and go on your way in peace, and let me continue on mine: I know that well-gotten gains can be lost, and ill-gotten ones can be lost, too, along with their owner.”

“I don’t want to insist, Sancho,” said Ricote, “but tell me: did you happen to be in our village when my wife, my daughter, and my brother-in-law left?”

“Yes, I was,” responded Sancho, “and I can tell you that your daughter looked so beautiful when she left that everybody in the village came out to see her, and they all said she was the fairest creature in the world. She was crying and embracing all her friends and companions, and all those who came out to see her, and asking them all to commend her to God and Our Lady, His Mother, and she did this with so much feeling it made me cry, though I’m not usually much of a weeper. By my faith, there were many who wanted to hide her and take her from those she was leaving with, but fear of defying the orders of the king stopped them. The one who seemed most affected was Don Pedro Gregorio, that rich young man who’s going to inherit his father’s estate, you know who I mean, they say he loved her very much, and after she left he’s never been seen in our village again, and we all think he went after them to abduct her, but so far we haven’t heard anything.”

“I always suspected,” said Ricote, “that he was wooing my daughter, but I trusted in the principles of my Ricota, and knowing he loved her never troubled me, because you must have heard, Sancho, that Moriscas rarely if ever become involved with Old Christians, and my daughter, who, I believe, cared more for being a better Christian than for being in love, would not pay attention to that young gentleman’s entreaties.”

“May it be God’s will,” replied Sancho, “because that would not be good for either one of them. And now let me leave here, Ricote my friend; tonight I want to reach the place where my master, Don Quixote, is.”

“God go with you, Sancho my friend; my companions are beginning to stir, and it’s time for us to leave, too.”

Then the two of them embraced, and Sancho mounted his donkey, and Ricote grasped his staff, and they went their separate ways.