Volume II (1615)

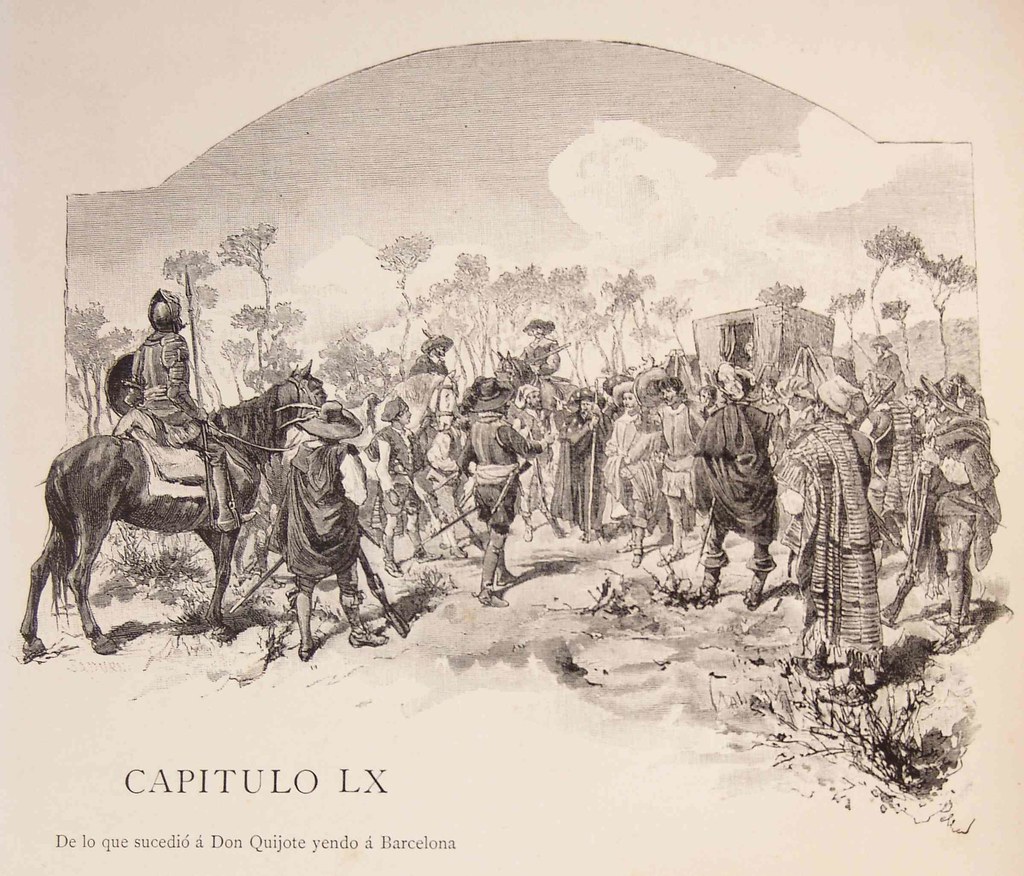

CHAPTER LX (click to read it in Spanish)

Concerning what befell Don Quixote on his way to Barcelona

The morning was cool, and it showed signs of remaining cool for the rest of the day when Don Quixote left the inn, first having learned the most direct road to Barcelona that avoided Zaragoza, so great was his desire to prove that the new historian, who, they said, had so maligned him, was a liar.

As it happened, in more than six days nothing occurred that was worth recording, but then, at the end of that time, when he had wandered away from the road, night overtook him in a thick stand of oak or cork trees; in this instance, Cide Hamete does not honor the exactitude he usually observes in such matters.

Master and servant climbed down from their mounts, and leaning against the tree trunks, Sancho, who had eaten that afternoon, allowed himself to rush headlong through the doors of sleep, but Don Quixote, whose imagination kept him awake much more than hunger did, could not close his eyes; instead, his thoughts wandered back and forth through a thousand different places. Now he seemed to find himself in the Cave of Montesinos; then he saw Dulcinea, transformed into a peasant, leaping onto the back of her donkey; next the words of the wise Merlin resounded in his ears, telling him the conditions that had to be met and the tasks that had to be completed in order to disenchant Dulcinea. He despaired to see the carelessness and lack of charity in Sancho his squire, who, he believed, had given himself only five lashes, a painfully small quantity considering the infinite number he still had to administer, and this caused him so much grief and anger that he reasoned in this fashion:

“If Alexander the Great cut the Gordian knot, saying: ‘It does not matter if it is cut or untied,’ and that did not keep him from being the universal lord of all Asia, then in the disenchantment of Dulcinea it might not matter if I whip Sancho against his will, for if the condition of this remedy is that Sancho receive some three thousand lashes, what difference does it make to me if he administers them himself or if another does, since the essence of the matter is that he receive them regardless of where they come from?”

With this thought in mind he approached Sancho, having first taken Rocinante’s reins and arranged them so that he could use them as a whip, and began to remove the cords that held up Sancho’s breeches, although it is believed he had them only in front; but no sooner had Don Quixote come up to him than Sancho started, fully awake, and said:

“What is it? Who’s touching me and untying my cords?”

“I am,” responded Don Quixote. “I have come to make up for your failings and to put an end to my travails: I have come to whip you, Sancho, and to discharge, in part, the debt you have assumed. Dulcinea perishes; you live in negligence; I die of desire; and so, expose yourself of your own free will, for mine is to give you at least two thousand lashes in this solitary place.”

“Oh, no,” said Sancho, “your grace had better stand still; if not, by the true God, even the deaf will hear us. The lashes I promised to give myself must be voluntary, not given by force, and now I don’t feel like lashing myself; it’s enough for me to give your grace my word to flog and thrash myself as soon as I feel that desire.”

“It must not be left to your courtesy, Sancho,” said Don Quixote, “because you have a hard heart, and although you are a peasant, your flesh is tender.”

And so he attempted and struggled to untie the cords, seeing which Sancho Panza got to his feet, rushed at his master in a fury, and tripped him so that he fell to the ground and lay there faceup; Sancho placed his right knee on his chest, and with his hands he held down his master’s hands, not allowing him to move and barely permitting him to breathe. Don Quixote said to him:

“What, you traitor? You dare to raise your hand against your natural lord and master? You presume to defy the person who gives you your bread?”

“I depose no king, I impose no king,” responded Sancho, “but I’ll help myself, for I’m my own lord.594 Promise me, your grace, that you’ll stay where you are, and won’t try to whip me now, and I’ll let you go and set you free; if not,

Oh, here you will die, you traitor

enemy of Doña Sancha.”595

Don Quixote promised and swore by his life and thoughts not to touch a thread of Sancho’s clothing and to leave the administering of the lashes entirely to his free will and desire.

Sancho got up and moved a good distance away, and as he was about to lean against another tree, he felt something graze his head, and he raised his hands and touched two feet in shoes and stockings. He trembled with fear and hurried to another tree, where the same thing happened. He shouted, calling for Don Quixote to help him. Don Quixote approached, asking what had happened and why he was afraid, and Sancho responded that all the trees were filled with human feet and legs. Don Quixote touched them and soon realized what they might be, and he said to Sancho:

“There is no need for you to be afraid, because these feet and legs that you touch but do not see undoubtedly belong to outlaws and bandits who have been hanged from these trees, for in this region the law usually hangs them when it catches them, in groups of twenty or thirty, which leads me to think I must be close to Barcelona.”596

And the truth was just as he had imagined it.

They looked up, apparently, and saw the bodies of bandits hanging from the branches of those trees. Just then dawn broke, and if the dead men had startled them, they were no less distressed by the more than forty live bandits who suddenly surrounded them, telling them in Catalan to stand still and be quiet until their captain arrived.

Don Quixote found himself on foot, his horse unbridled, his lance leaning against a tree, in short, with no defenses at all, and so he considered it the wisest course to fold his hands, bow his head, and wait for a better occasion and opportunity.

The bandits quickly looked over the gray and left nothing in the saddlebags and traveling case; it was Sancho’s good fortune that he carried the duke’s escudos and the ones he had brought from home tightly bound in a sash he wore around his stomach, and even so, those good people would have searched and dug down to what he had hidden between his skin and his flesh if their captain had not arrived at that point; he seemed to be about thirty-four years old and was robust, of more than medium height, with a solemn gaze and a dark complexion. He was riding a powerful horse, wearing a halberk,597 and carrying four pistols, which in that country are called pedreñales, 598 at his sides. He saw that his squires—the name given to those who engage in this practice—were about to strip Sancho Panza; he ordered them to stop and was obeyed instantly, and so the sash escaped. He was surprised to see a lance leaning against a tree, a shield on the ground, and a pensive Don Quixote in armor, with a face sadder and more melancholy than anything sadness itself could fashion. He went up to him, saying:

“Do not be so sad, my good man, for you have not fallen into the hands of some cruel Osiris,599 but into those of Roque Guinart,600 and his are more compassionate than severe.”

“My sadness,” responded Don Quixote, “is not that I have fallen into your hands, O valorous Roque, whose fame reaches far beyond the borders of your land, but because my negligence was so great that your soldiers found me unprepared, when I am obliged, according to the order of knight errantry which I profess, to be constantly on the alert, and at all hours to serve as my own sentinel; because I assure you, O great Roque, that if they had found me on my horse, with my lance and shield, it would not have been very easy for them to defeat me, for I am Don Quixote of La Mancha, he whose exploits are known all over the world.”

Then Roque Guinart realized that Don Quixote’s infirmity was closer to madness than to valor, and although he had heard about him on occasion, he never had considered his deeds to be true, for he could not convince himself that this kind of humor could control the heart of a man; he was extremely pleased to have encountered him and therefore touch in proximity what he had heard about at a distance, and so he said:

“Valorous knight, do not be indignant or consider the circumstance in which you find yourself sinister; it may be that by means of these difficulties your tortuous fortunes will be set straight, for heaven, by strange, inconceivable turnings which men cannot imagine, tends to raise the fallen and enrich the poor.”

Don Quixote was about to thank him when at their backs they heard a noise that sounded like a troop of horses, but it was only one, ridden in a fury by a young man who seemed to be about twenty years old and was dressed in green damask breeches and coat, both trimmed in gold, a plumed hat worn at an angle, close-fitting waxed boots, spurs, a golden dagger and a sword, a small flintlock in his hand, and two pistols at his sides. At the sound Roque turned his head and saw this beautiful figure, who rode up to him and said:

“I have come looking for you, O valorous Roque, to find in you if not a remedy, at least relief for my misfortune; and so as not to keep you in suspense, because I know you have not recognized me, I want to tell you who I am: I am Claudia Jerónima, daughter of Simón Forte, your dear friend and the particular enemy of Clauquel Torrellas, who is also your enemy because he belongs to the faction that opposes you;601 and you already know that this Torrellas has a son named Don Vicente Torrellas, or, at least, that was his name two hours ago. To make the story of my misfortune short, I shall tell you briefly the grief he has caused me. He saw me and flattered me, I listened to him and fell in love, behind my father’s back, because there is no woman, no matter how secluded her life and no matter how modest her nature, who does not have more than enough time to execute and put into effect her transgressive desires. In short, he promised to be my husband, and I gave him my word that I would be his wife, though we did not pass beyond that into actions. I learned yesterday that he had forgotten what he owed me and was marrying another; the wedding was to take place this morning, a piece of news that troubled my judgment and put an end to my patience; since my father was away, I put on these clothes that you see, and rode this horse at a gallop until I overtook Don Vicente about a league from here, and not bothering to complain, or to listen to excuses, I fired this flint-lock at him, and these two pistols as well, and I believe I must have put more than two bullets in his body, opening doors through which my honor, mixed with his blood, could pour out. I left him there with his servants, who did not dare to, or could not, defend him. I have come to find you so that you can get me across the border into France, where I have kinfolk with whom to live, and also to implore you to defend my father so that Don Vicente’s many supporters will not dare wreak a terrible vengeance on him.”

Roque, marveling at the lovely Claudia’s gallantry, courage, beautiful appearance, and remarkable story, said:

“Come, Señora, and let us see if your enemy is dead, and then we shall see what it is best for you to do.”

Don Quixote, who had been listening attentively to what Claudia said and how Roque Guinart responded, said:

“No one need bother to defend this lady, for I take that responsibility as mine; give me my horse and my arms, and wait for me here, and I shall find this knight and, whether he is dead or alive, I shall oblige him to keep the promise he made to such great beauty.”

“Nobody should doubt that,” said Sancho, “because my master is a very good hand at matchmaking: not many days ago he obliged another man to marry who had also denied his promise to another maiden, and if it wasn’t because the enchanters who pursue him changed that man’s real face into a footman’s, by now that maiden would no longer be one.”

Roque, who was more concerned with thinking about what had happened to the beautiful Claudia than with the words of master and servant, did not hear them, and after ordering his squires to return to Sancho everything they had taken from the gray, he also ordered them to withdraw to the place where they had spent the night, and then he galloped away with Claudia to find the wounded or dead Don Vicente. They reached the place where Claudia had met him and found nothing there except recently spilled blood, but they looked all around and saw some people climbing a hill, and they assumed, which was the truth, that it must be Don Vicente, dead or alive, carried by his servants to be healed or buried; they hurried to reach them, and since they were climbing slowly, this was an easy matter.

They found Don Vicente in the arms of his servants, imploring in a faint and feeble voice that they leave him there to die, because the pain of his wounds would not permit him to go any farther.

Claudia and Roque leaped from their horses and approached him; the servants were frightened at the presence of Roque, and Claudia was disquieted at the sight of Don Vicente, and with a mixture of compassion and harshness she went up to him, grasped his hands, and said:

“If you had given me these and abided by our agreement, this never would have happened to you.”

The wounded gentleman opened his half-closed eyes, and recognizing Claudia, he said:

“I see clearly, beautiful and deceived lady, that you were the one who killed me, a punishment I did not deserve or merit, for neither with my desires nor my actions did I ever wish or intend to offend you.”

“Then, isn’t it true,” said Claudia, “that this morning you were going to marry Leonora, the daughter of the wealthy Balvastro?”

“No, certainly not,” responded Don Vicente. “My ill fortune must have brought you that news so that you, in jealousy, would take my life, but since I leave it in your hands and arms, I consider my luck to be good. And in order to assure yourself that this is true, press my hand and accept me as your husband, if you like, for I have no greater satisfaction to give you for the injury you think you have received from me.”

Claudia pressed his hand, and her own heart felt pressed, causing her to faint onto the bloody bosom of Don Vicente, who was shaken by a mortal paroxysm. Roque was bewildered and did not know what to do. The servants hurried to find water to sprinkle on the lovers’ faces, and they brought some and bathed their faces with it. Claudia recovered from her swoon, but not Don Vicente from his paroxysm, because his life had ended. Seeing this, Claudia realized that her sweet husband was no longer alive, and she pierced the air with sighs, wounded the heavens with lamentations, tore her hair and threw it into the wind, scratched her face with her own hands, and showed all the signs of sorrow and grief that could be imagined in a wounded heart.

“O cruel and thoughtless woman,” she said, “how easily you were moved to act upon so evil a thought! O raging power of jealousy, to what a desperate end you led one who sheltered you in her bosom! O husband of mine, because you were loved by me, your unfortunate fate has brought you from the nuptial bed to the grave!”

Claudia’s lamentations were so sad that they brought tears to Roque’s eyes, which were not accustomed to shed them under any circumstances. The servants wept, Claudia fainted over and over again, and the area around them seemed to be a field of sorrow and a place of misfortune. Finally Roque Guinart ordered the servants to carry Don Vicente’s body to his father’s house, which was nearby, for burial. Claudia told Roque that she wanted to go to a convent where an aunt of hers was abbess, and there she intended to end her days in the company of a better, and an eternal, husband. Roque praised her good intention and offered to accompany her wherever she wished and to defend her father against Don Vicente’s kin, and anyone else, if they tried to injure him. On no account did Claudia wish his company, and after thanking him for his offers with the best words she knew, she took her leave of him in tears. Don Vicente’s servants carried away his body, and Roque returned to his people, and so ended the love story of Claudia Jerónima. But what other ending could it have if the threads of her pitiable tale were woven by the invincible and cruel forces of jealousy?

Roque Guinart found his squires in the place where he had ordered them to wait; Don Quixote was with them, mounted on Rocinante and speaking to them in an attempt to persuade them to abandon a mode of life so dangerous for both the soul and the body, but since most of them were Gascons,602 a crude and unruly people, they were not particularly influenced by Don Quixote’s discourse. When Roque arrived, he asked Sancho Panza if his men had returned and restored to him the gems and jewels they had taken from the gray. Sancho responded that they had, but he was missing three nightcaps that were worth three cities.

“Man, what are you saying?” said one of the outlaws. “I have them, and they’re not worth three reales.”

“That is true,” said Don Quixote, “but my squire values them in the manner he has said because of the person who gave them to me.”

Roque Guinart commanded that they be returned immediately, and after ordering his men into a line, he said that all the clothing, jewels, and money, everything they had stolen since the last distribution, should be placed in front of them; and after quickly making an estimate and setting aside what could not be divided and reducing it to money,603 he distributed goods to his entire company with so much equity and prudence that he adhered absolutely to distributive justice and gave no one too much or too little. When this had been concluded, and everyone was content, satisfied, and well-paid, Roque said to Don Quixote:

“If one were not scrupulous with these men, there would be no way to live with them.”

To which Sancho said:

“According to what I’ve seen here, justice is so great a good that it’s necessary to use it even among thieves.”

One of the squires heard this, and he raised the butt of a harquebus and undoubtedly would have used it to crack open Sancho’s skull if Roque Guinart had not shouted at him to stop. Sancho was terrified, and he resolved not to open his mouth again for as long as he was among those people.

Just then, one or some of the squires who had been posted as sentinels along the roads to watch the travelers and to inform their leader about everything that happened, came up to Roque and said:

“Señor, not far from here there’s a large group of people traveling along the Barcelona road.”

To which Roque responded:

“Could you see if they’re the kind who come looking for us, or the kind we go looking for?”

“They’re the kind we go looking for,” responded the squire.

“Then all of you go,” replied Roque, “and bring them here to me, and don’t let a single one escape.”

They did as he said, and Don Quixote, Sancho, and Roque were left alone, waiting to see what the squires would bring back; and while they were waiting, Roque said to Don Quixote:

“Our manner of life must seem unprecedented to Señor Don Quixote: singular adventures, singular events, and all of them dangerous; I don’t wonder that it seems this way to you, because really, I confess there is no mode of life more unsettling and surprising than ours. Certain desires for revenge brought me to it, and they have the power to trouble the most serene heart; by nature I am compassionate and well-intentioned, but, as I have said, my wish to take revenge for an injury that was done to me threw all my good inclinations to the ground, and I continue in this state in spite of and despite my understanding; as one abyss calls to another abyss, and one sin to another sin, vengeance has linked with vengeance so that I bear responsibility not only for mine but for those of others, but it is God’s will that although I find myself in the midst of a labyrinth of my own confusions, I do not lose the hope of coming out of it and into a safe harbor.”

Don Quixote was amazed to hear Roque speak so well and so reasonably, because he had thought that among those whose profession it was to rob, kill, and steal, there could be no one who was well-spoken, and he responded:

“Señor Roque, the beginning of health lies in knowing the disease, and in the patient’s willingness to take the medicines the doctor prescribes; your grace is ill, you know your ailment, and heaven, or I should say God, who is our physician, will treat you with the medicines that will cure you, and which tend to cure gradually, not suddenly and miraculously; furthermore, intelligent sinners are closer to reforming than simpleminded ones, and since your grace has demonstrated prudence in your speech, you need only be brave and wait for the illness of your conscience to be healed; if your grace wishes to save time and put yourself without difficulty on the road to salvation, come with me, and I shall teach you how to be a knight errant, a profession in which one undergoes so many trials and misfortunes that, if deemed to be penance, they would bring you to heaven in the wink of an eye.”

Roque laughed at the advice of Don Quixote and then, changing the subject, recounted the tragic story of Claudia Jerónima, which caused Sancho great sorrow, for he had liked the girl’s beauty, confidence, and spirit.

Then the squires arrived with their prey, bringing with them two gentlemen on horseback, and two pilgrims on foot, and a carriage of women with six servants who accompanied them, mounted and on foot, and two muledrivers who were with the gentlemen. The squires kept them surrounded, and both the vanquished and the victors maintained a deep silence, waiting for the great Roque Guinart to speak, and he asked the gentlemen who they were and where they were going and how much money they were carrying. One of them responded:

“Señor, we are two captains of the Spanish infantry: our companies are in Naples and we are going to embark on four galleys that, we are told, are in Barcelona under orders to sail to Sicily; we are carrying two or three hundred escudos, which, in our opinion, makes us rich and content, for the ordinary poverty of soldiers does not allow greater treasure.”

Roque asked the pilgrims the same questions he had asked the captains; they responded that they were going to embark for Rome and that between the two of them they might have some sixty reales. He also wanted to know who was riding in the carriage, and where they were going, and how much money they were carrying, and one of the men on horseback said:

“My lady Doña Guiomar de Quiñones, the wife of the chief magistrate of the vicariate of Naples, with her little daughter, a maid, and a duenna, are riding in the carriage; we are six servants who are accompanying her, and the money amounts to six hundred escudos.”

“That means,” said Roque Guinart, “that we have here nine hundred escudos and sixty reales; my soldiers number about sixty; see how much is owed to each of them, because I don’t count very well.”

When they heard this, the robbers raised their voices, shouting:

“Long live Roque Guinart in spite of the lladres 604 who are trying to ruin him!”

The captains showed their grief, the magistrate’s wife grew sad, and the pilgrims were not at all happy at the confiscation of their goods. Roque kept them in suspense for a while, but he did not want their sorrow to continue, for by now it could be seen a harquebus’s shot away, and turning to the captains, he said:

“Señores, would your graces please be so kind as to lend me sixty escudos, and the lady eighty, to keep this squadron of mine happy, for the abbot eats if the tithes are paid, and then you can go on your way free and unimpeded, and with a safe conduct that I’ll give you, and if you happen to meet other squadrons of mine in the vicinity, no harm will be done to you, for it is not my intention to injure soldiers or women, especially those who are highborn.”

Infinite and well-spoken words were used by the captains to thank Roque for his courtesy and liberality, for that is what they considered his leaving them their money. Señora Doña Guiomar de Quiñones wanted to leap out of her carriage to kiss the feet and hands of the great Roque, but he would not consent on any account; instead, he begged her pardon for the injury he had done to her, forced on him by the strict obligations of his evil profession. The chief magistrate’s wife ordered one of her servants to immediately give him the eighty escudos that were her share, and the captains had already taken their sixty out of the purse. The pilgrims were about to offer all of their paltry wealth, but Roque told them to be still, and turning to his men, he said:

“Of these escudos, two go to each man, and that leaves twenty; ten should go to these pilgrims, and the other ten to this good squire so that he can speak well of this adventure.”

His men brought him the writing materials that he always carried with him, and Roque wrote out a safe conduct addressed to the chiefs of his squadrons, and then he said goodbye to the travelers and let them go, and they were astonished at his nobility, his gallant disposition, and unusual behavior, thinking of him more as an Alexander the Great than as a well-known thief. One of his squires said in his Gascon and Catalan language:

“This captain of ours is more of a frade 605 than a bandit: if he wants to be generous from now on, let it be with his goods, not ours.”

The unfortunate man did not speak quietly enough, and Roque heard him, drew his sword, and split his head almost in two, saying:

“This is how I punish insolent men who talk too much.”

Everyone was terrified, and no one dared say a word: that was the obedience they showed him.

Roque moved to one side and wrote a letter to a friend of his in Barcelona, informing him that the famous Don Quixote of La Mancha, the knight errant about whom so many things had been said, was with him, and telling his friend that the knight was the most amusing and best-informed man in the world, and that in four days’ time, which was the feast of St. John the Baptist,606 he would present himself along the shore of the city, armed with all his armor and weapons, mounted on his horse, Rocinante, with his squire, Sancho, riding a donkey; Roque asked his friend to inform his friends the Niarros so that they could derive pleasure from this, but he wished to deprive his enemies the Cadells607 of this amusement; it was impossible, however, because the madness and intelligence of Don Quixote, and the wit of his squire, Sancho Panza, could not help but give pleasure to everyone. He dispatched the letter with one of his squires, who changed his bandit’s clothes for those of a peasant, and entered Barcelona, and delivered it to the person to whom it was addressed.