Volume II (1615)

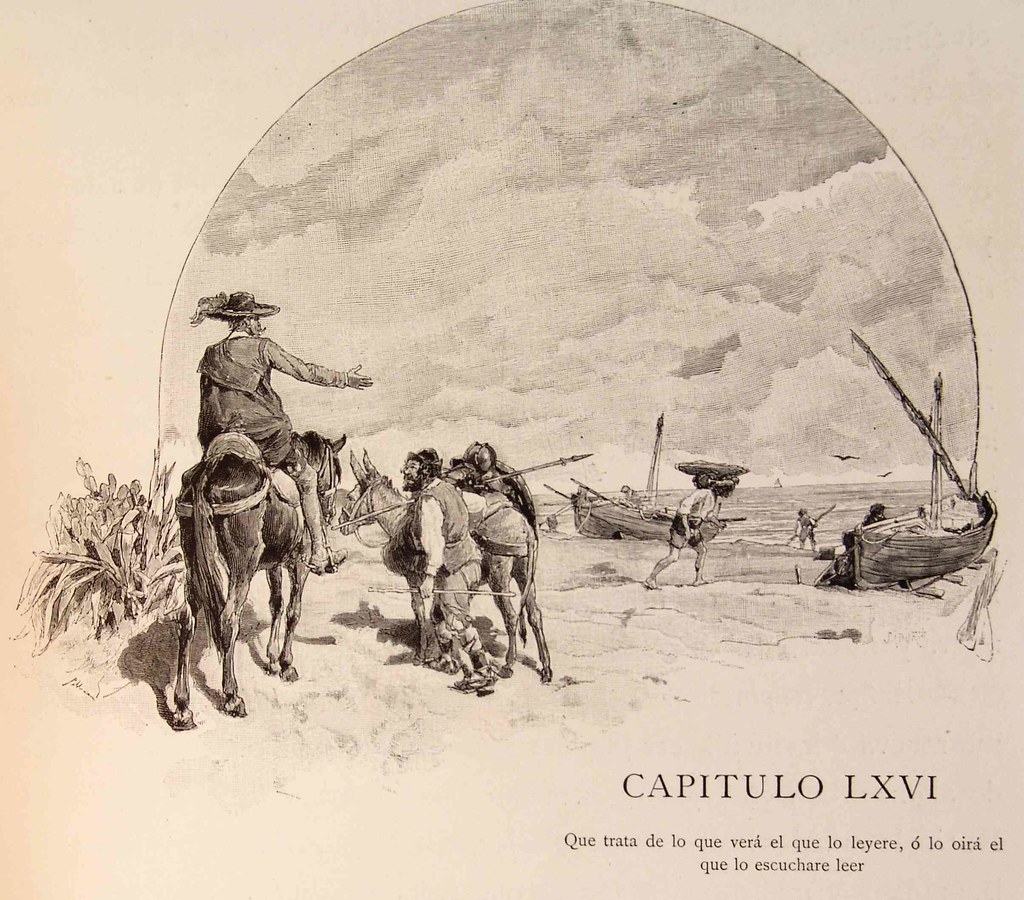

Which recounts what will be seen by whoever reads it, or heard by whoever listens to it being read

As he left Barcelona, Don Quixote turned to look at the place where he had fallen, saying:

“Here was Troy! Here my misfortune, not my cowardice, did away with the glories I had achieved; here Fortune turned her changes and reverses against me; here my deeds were obscured; here, in short, my happiness fell, never to rise again!”

When Sancho heard this, he said:

“Señor, it is as fitting for valiant hearts to endure misfortune as it is for them to rejoice in prosperity; and I judge this on the basis of my own experience, for if I was happy when I was governor, now that I’m a squire on foot, I’m not sad, because I’ve heard that the woman they call Fortune is drunken, and fickle, and most of all blind, so she doesn’t see what she’s doing and doesn’t know who she’s throwing down or raising up.”

“You sound very philosophical, Sancho,” responded Don Quixote, “and you speak very wisely; I do not know who taught that to you. What I can say is that there is no fortune in the world, and the things that happen in it, whether good or bad, do not happen by chance but by the particular providence of heaven, which is why people say that each man is the architect of his own fortune. I have done that with mine, but without the necessary prudence, and so my assumptions have turned out badly, for I should have realized that Rocinante’s weakness could not resist the power and size of the horse belonging to the Knight of the White Moon. In short, I took a risk, I did what I could, I was toppled, and although I lost my honor, I did not lose, nor can I lose, the virtue of keeping my word. When I was a knight errant, daring and brave, my acts and my hands brought credit to my deeds, and now, when I am an ordinary gentleman, I shall bring credit to my words by keeping the promise I made. Walk on, then, Sancho my friend, and let us go home to spend the year of our novitiate, and in that seclusion we shall gather new strength to return to the practice of arms, which will never be forgotten by me.”

“Señor,” responded Sancho, “traveling on foot is not so pleasant a thing that it leads or moves me to travel a great distance each day. Let’s leave this armor hanging from some tree instead of a hanged man, and if I can sit on my gray, with my feet off the ground, we’ll travel whatever distances your grace asks for and decides, but if you think I’ll walk great distances on foot, you’d better think again.”

“You have spoken well, Sancho,” responded Don Quixote. “Let my armor be hung as a trophy, and beneath it, or all around it, we shall carve on the trees what was written on the trophy of Roland’s arms:

Let no one move them

who cannot test his own against Roland.”628

“That all seems like pearls to me,” responded Sancho, “and if we weren’t going to need Rocinante on the road, it would be a good idea to leave him hanging, too.”

“Well,” replied Don Quixote, “I do not want either him or my arms hanged, so that no one can say this is a bad reward for good service!”

“Your grace is right,” responded Sancho, “because according to wise men, you shouldn’t blame the packsaddle for the donkey’s mistake, and since your grace is to blame for what happened, you should punish yourself and not turn your anger against your battered and bloody arms, or the gentle Rocinante, or my tender feet by wanting them to walk more than is fair.”

They spent all that day in this kind of talk and conversation, and another four as well, and nothing happened to interfere with their journey, but on the fifth day, at the entrance to a village, they discovered a crowd of people at the door of an inn, for it was a holiday and they were there enjoying themselves. When Don Quixote reached them, a peasant raised his voice, saying:

“One of these two gentlemen, who don’t know the parties, can decide our wager.”

“I shall, certainly,” responded Don Quixote, “and with complete rectitude, if I can understand it.”

“Well then, Señor,” said the peasant, “the fact is that a man from this village, so fat he weighs eleven arrobas, challenged a neighbor of his, who doesn’t weigh more than five, to a race. The condition was that they had to run a hundred paces carrying equal weight, and when the challenger was asked how they would equal the weight he said that the other man, who weighs five arrobas, should add another six arrobas of iron on his back, and in this way the thin man’s eleven arrobas would match the eleven of the fat man.”

“Oh no,” said Sancho before Don Quixote could respond. “Just a few days ago I stopped being a governor, and it’s up to the judge, as everybody knows, to decide questions and give an opinion in every case.”

“You are welcome to respond,” said Don Quixote, “Sancho my friend; I would not be competent to do so, my judgment is so shaken and confused.”

With this permission, Sancho said to the peasants, who stood around him with their mouths open, waiting for his verdict:

“Brothers, what the fat man asks for is not fair and doesn’t have a shred of justice in it, because if what they say is true, and the one who’s challenged can choose his weapons, it isn’t right for him to choose ones that would keep him or stop him from being victorious, and so it’s my opinion that the fat challenger should prune, trim, peel away, scrape, pare off, and lose six arrobas of his flesh, here and there on his body, wherever he thinks best, and in this way, when he weighs five arrobas, he’ll match and be equal to the five of his adversary, and so they’ll be able to run carrying equal weight.”629

“By my soul!” said a peasant who had listened to Sancho’s decision. “This gentleman has spoken like a saint and given a verdict like a canon! But I’ll bet the fat man won’t want to lose an ounce of his flesh, let alone six arrobas of it.”

“The best thing would be if they don’t run,” responded another, “because then the thin man won’t be worn out carrying that weight, and the fat man won’t have to lose any; let half the wager be in wine, and let’s take these gentlemen to the tavern that has the good wine, and let it be on me…and wear a cape when it rains.”

“Señores,” responded Don Quixote, “I thank you, but I cannot stop even for a moment; melancholy thoughts and events make me seem discourteous and oblige me to travel quickly.”

And so, spurring Rocinante, he rode forward, leaving them all amazed at having seen and observed both his strange figure and the intelligence of his servant, for that is what they judged Sancho to be. And another of the peasants said:

“If the servant is this intelligent, what must the master be like! I’ll bet if they went to study in Salamanca, in the wink of an eye they’d be magistrates; everything’s deceit except studying and more studying, and having favor and good luck; when a man least expects it, he finds himself with a staff in his hand or a mitre on his head.”

Master and servant spent that night in the middle of a field, in the open air; the next day, as they continued their journey, they saw a man walking toward them, with saddlebags around his neck and a pike or javelin in his hand, looking exactly like a courier on foot; as he approached Don Quixote, he quickened his pace until he was almost running, and he came up to him and embraced his right thigh, which was as high as he could reach, and said with displays of great joy:

“Oh, Señor Don Quixote of La Mancha, what happiness will fill the heart of my lord the duke when he knows that your grace is returning to his castle, for he is still there with my lady the duchess!”

“I do not recognize you, friend,” responded Don Quixote, “and I shall not know who you are if you do not tell me.”

“I, Señor Don Quixote,” responded the courier, “am Tosilos, the footman of my lord the duke who refused to fight with your grace over marrying the daughter of Doña Rodríguez.”

“God save me!” said Don Quixote. “Is it possible that you are the one whom the enchanters, my enemies, transformed into the footman you mention in order to cheat me of the honor of that combat?”

“Be quiet, Señor,” replied the letter carrier. “There was no enchantment at all, and no change in anybody’s face: I entered the field as much Tosilos the footman as I was when I left it. I wanted to marry without fighting, because I liked the girl’s looks, but things turned out just the opposite of my intention, because as soon as your grace left our castle, my lord the duke had me lashed a hundred times for going against the orders he had given me before I went into combat, and the upshot is that the girl is a nun, and Doña Rodríguez has gone back to Castilla, and I’m going now to Barcelona to bring a packet of letters to the viceroy that my master has sent him. If your grace would like a drink that’s pure, though warm, I have a gourd filled with good wine, and a few slices of Tronchón cheese that will call upon and wake your thirst if it happens to be sleeping.”

“I’ll see this bet,” said Sancho, “and stake it all on courtesy, and let good Tosilos pour in spite of and despite all the enchanters in the Indies.”

“Well, well,” said Don Quixote, “you are, Sancho, the greatest glutton in the world, and the most ignorant man on earth, for you cannot be persuaded that this courier is enchanted and this Tosilos a counterfeit. Stay with him, and drink your fill, and I shall go ahead slowly and wait for you until you come.”

The footman laughed, uncovered his gourd, and took his cheese and a small loaf of bread out of a saddlebag, and he and Sancho sat on the green grass and in companionable peace quickly dispatched and finished the contents of the saddlebags with so much spirit that they licked the packet of letters simply because it smelled of cheese. Tosilos said to Sancho:

“There’s no doubt that your master, Sancho my friend, must be a madman.”

“What do you mean, ‘must be’?” responded Sancho. “He doesn’t owe anybody anything;630 he pays for everything, and more, when madness is the coin. I see it clearly, and I tell him so clearly, but what good does it do? Especially now, when he’s really hopeless because he was defeated by the Knight of the White Moon.”

Tosilos begged him to tell him what had happened, but Sancho responded that it was discourteous to allow his master to wait for him, and on another day, if they were to meet, there would be time for that. And having stood after he had shaken his tunic and brushed the crumbs from his beard, he walked behind the gray, said goodbye, left Tosilos, and overtook his master, who was waiting for him in the shade of a tree.