Volume II (1615)

In which the adventure of the Knight of the Wood continues, along with perceptive, unprecedented, and amiable conversation between the two squires

Knights and squires were separated, the latter recounting their lives and the former their loves, but the history first relates the conversation of the servants and then goes on to that of their masters, and so it says that as they moved a short distance away, the Squire of the Wood said to Sancho:

“We have a difficult life, Señor, those of us who are squires to knights errant: the truth is we eat our bread by the sweat of our brow, which is one of God’s curses on our first parents.”

“You could also say,” added Sancho, “that we eat it in the icy cold of our bodies, because who suffers more heat and cold than the wretched squires of knight errantry? If we ate, it would be easier because sorrows fade with a little bread, but sometimes we can go a day or two with nothing for our breakfast but the wind that blows.”

“All of this is made bearable and tolerable,” said the Squire of the Wood, “by our hope of a reward, because if the knight errant is not too unfortunate, in a little while the squire who serves him will be rewarded with an attractive governorship of an ínsula or a fine countship.”

“I,” replied Sancho, “have already told my master that I’ll be content with the governorship of an ínsula, and he’s so noble and generous that he’s promised it to me on many different occasions.”

“I,” said the Squire of the Wood, “will be satisfied with a canonship as payment for my services, and my master has already set one aside for me, and what a nice canonship it is!”

“Your grace’s master,” said Sancho, “must be an ecclesiastical kind of knight who can do favors like that for his good squires, but mine is a lay knight, though I do remember when some very wise people, though I think they were malicious, too, advised him to become an archbishop, but he only wanted to be an emperor, and I was trembling at the thought that he’d decide to enter the Church, because I didn’t think I was qualified to hold any benefices, because I can tell your grace that even though I look like a man, I’m nothing but an animal when it comes to entering the Church.”

“Well, the truth is your grace is mistaken,” said the Squire of the Wood, “because not all insular governorships are good. Some are crooked, some are poor, and some are gloomy, and even the proudest and best of them bring a heavy burden of cares and troubles that has to be borne on the shoulders of the unlucky man who happens to be governor. It would be much better for those of us who perform this miserable service to return home and do some easier work, like hunting or fishing, for is there any squire in the world so poor he doesn’t have a horse, a couple of greyhounds, and a fishing pole to help him pass the time?”

“I have all those things,” responded Sancho. “Well, the truth is I don’t have a horse, but my donkey is worth twice as much as my master’s nag. May God send me evil days, starting tomorrow, if I’d ever trade with him, even if he threw in four bushelweights of barley. Your grace must think I’m joking about the value I put on my gray, for gray is the color of my donkey. And I wouldn’t need greyhounds because there are plenty of them in my village; besides, hunting is much nicer when you do it at somebody else’s expense.”

“The truth of the matter, Señor Squire,” responded the Squire of the Wood, “is that I’ve decided and resolved to leave the crazy goings-on of these knights and go back to my village and rear my children, for I have three as beautiful as Oriental pearls.”

“I have two,” said Sancho, “who could be presented to the pope himself, especially the girl, who I’m bringing up to be a countess, God willing, though her mother’s against it.”

“And how old is this lady who’s being brought up to be a countess?” asked the Squire of the Wood.

“Fifteen, give or take a couple of years,” responded Sancho, “but she’s as tall as a lance, and as fresh as a morning in April, and as strong as a laborer.”

“Those are qualities,” responded the Squire of the Wood, “for being not only a countess but a nymph of the greenwood. O whoreson, but that damned little whore must be strong!”

To which Sancho replied, rather crossly:

“She isn’t a whore, and neither was her mother, and neither of them will ever be one, God willing, as long as I’m alive. And speak more politely; for somebody who’s spent time with knights errant, who are courtesy itself, your grace isn’t very careful about your words.”

“Oh, Señor Squire, how little your grace understands,” replied the Squire of the Wood, “about paying a compliment! Can it be that you don’t know that when a knight gives the bull in the square a good thrust with the lance, or when anybody does anything well, commoners always say: ‘Oh whoreson, but that damned little whoreson did that well!’? And in that phrase, what seems to be an insult is a wonderful compliment, and you should disavow, Señor, any sons or daughters who do not perform deeds that bring their parents that kind of praise.”

“I do disavow them,” responded Sancho, “and in that sense and for that reason your grace could dump a whole whorehouse on me and my children and my wife, because everything they do and say deserves the best compliments, and I want to see them again so much that I pray God to deliver me from mortal sin, which would be the same as delivering me from this dangerous squirely work that I’ve fallen into for a second time, tempted and lured by a purse with a hundred ducados that I found one day in the heart of the Sierra Morena; and the devil places before my eyes, here, there, not here but over there, a sack filled with doblones, and at every step I take I seem to touch it with my hand, and put my arms around it, and take it to my house, and hold mortgages, and collect rents, and live like a prince, and when I’m thinking about that, all the trials I suffer with this simpleton of a master seem easy to bear, even though I know he’s more of a madman than a knight.”

“That,” responded the Squire of the Wood, “is why they say that it’s greed that tears the sack, and if we’re going to talk about madmen, there’s nobody in the world crazier than my master, because he’s one of those who say: ‘Other people’s troubles kill the donkey,’ and to help another knight find the wits he’s lost, he pretends to be crazy and goes around looking for something that I think will hit him right in the face when he finds it.”

“Is he in love, by any chance?”

“Yes,” said the Squire of the Wood, “with a certain Casildea of Vandalia, the cruelest lady in the world, and the hardest to stomach, but indigestibility isn’t her greatest fault; her other deceits are growling in his belly, and they’ll make themselves heard before too many hours have gone by.”

“There’s no road so smooth,” replied Sancho, “that it doesn’t have some obstacle or stumbling block; they cook beans everywhere, but in my house they do it by the potful; craziness must have more companions and friends than wisdom. But if what they say is true, that misery loves company, then I can find comfort with your grace, because you serve a master who’s as great a fool as mine.”

“A fool, but brave,” responded the Squire of the Wood, “and more of a scoundrel than foolish or brave.”

“Not mine,” responded Sancho. “I mean, there’s nothing of the scoundrel in him; mine’s as innocent as a baby; he doesn’t know how to harm anybody, he can only do good to everybody, and there’s no malice in him: a child could convince him it’s night in the middle of the day, and because he’s simple I love him with all my heart and couldn’t leave him no matter how many crazy things he does.”

“Even so, Señor,” said the Squire of the Wood, “if the blind man leads the blind man, they’re both in danger of falling into the ditch. Brother, we’d better leave soon and go back where we came from; people who look for adventures don’t always find good ones.”

Sancho had been spitting often, it seems, a certain kind of sticky, dry saliva, and the charitable woodish squire, seeing and noting this, said:

“I think we’ve talked so much our tongues are sticking to the roofs of our mouths, but I have an unsticker hanging from my saddlebow, and it’s a pretty good one.”

And he stood up and came back in a little while carrying a large wineskin and a meat pie half a meter long, and this is not an exaggeration, because it held a white rabbit so large that Sancho, when he touched it, thought it was a goat, and not a kid, either; and when Sancho saw this, he said:

“Señor, did you bring this with you?”

“Well, what did you think?” responded the other man. “Am I by any chance a run-of-the-mill squire? I carry better provisions on my horse’s rump than a general does when he goes marching.”

Sancho ate without having to be asked twice, and in the dark he wolfed down mouthfuls the size of the knots that hobble a horse. And he said:

“Your grace is a faithful and true, right and proper, magnificent and great squire, as this feast shows, and if you haven’t come here by the arts of enchantment, at least it seems that way to me; but I’m so poor and unlucky that all I have in my saddlebags is a little cheese, so hard you could break a giant’s skull with it, and to keep it company some four dozen carob beans and the same number of hazelnuts and other kinds of nuts, thanks to the poverty of my master and the idea he has and the rule he keeps that knights errant should not live and survive on anything but dried fruits and the plants of the field.”

“By my faith, brother,” replied the Squire of the Wood, “my stomach isn’t made for thistles or wild pears or forest roots. Let our masters have their knightly opinions and rules and eat what their laws command. I have my baskets of food, and this wineskin hanging from the saddlebow, just in case, and I’m so devoted to it and love it so much that I can’t let too much time pass without giving it a thousand kisses and a thousand embraces.”

And saying this, he placed the wineskin in Sancho’s hands, who tilted it back and put it to his mouth and looked at the stars for a quarter of an hour, and when he had finished drinking, he leaned his head to one side, heaved a great sigh, and said:

“O whoreson, you damned rascal, but that’s good!”

“Do you see?” said the Squire of the Wood when he heard Sancho’s “whoreson.” “You complimented the wine by calling it whoreson.”

“And I say,” responded Sancho, “that I confess to knowing it’s no dishonor to call anybody a whoreson when your intention is to compliment him. But tell me, Señor, by the thing you love most: is this wine from Ciudad Real?”

“Bravo! What a winetaster!” responded the Squire of the Wood. “It’s from there and no place else, and it’s aged a few years.”

“You can’t fool me!” said Sancho. “You shouldn’t think it was beyond me to know about this wine. Does it surprise you, Señor Squire, that I have so great and natural an instinct for knowing wines that if I just smell one I know where it comes from, its lineage, its taste, its age, and how it will change, and everything else that has anything to do with it? But it’s no wonder, because in my family, on my father’s side, were the two best winetasters that La Mancha had in many years, and to prove it I’ll tell you a story about them. The two of them were asked to taste some wine from a cask and say what they thought about its condition and quality, and whether it was a good or bad wine. One tasted it with the tip of his tongue; the other only brought it up to his nose. The first said that the wine tasted of iron, the second that it tasted more of tanned leather. The owner said the cask was clean and the wine had not been fortified in a way that could have given it the taste of iron or leather. Even so, the two famous winetasters insisted that what they said was true. Time passed, the wine was sold, and when the cask was cleaned, inside it they found a small key on a leather strap. So your grace can see that a man who comes from that kind of family can give his opinion about matters like these.”

“That’s why I say,” said the Squire of the Wood, “that we should stop looking for adventures, and if we have loaves of bread, we shouldn’t go around looking for cakes, and we ought to go back home: God will find us there, if He wants to.”

“I’ll serve my master until he gets to Zaragoza; after that, we’ll work out something.”

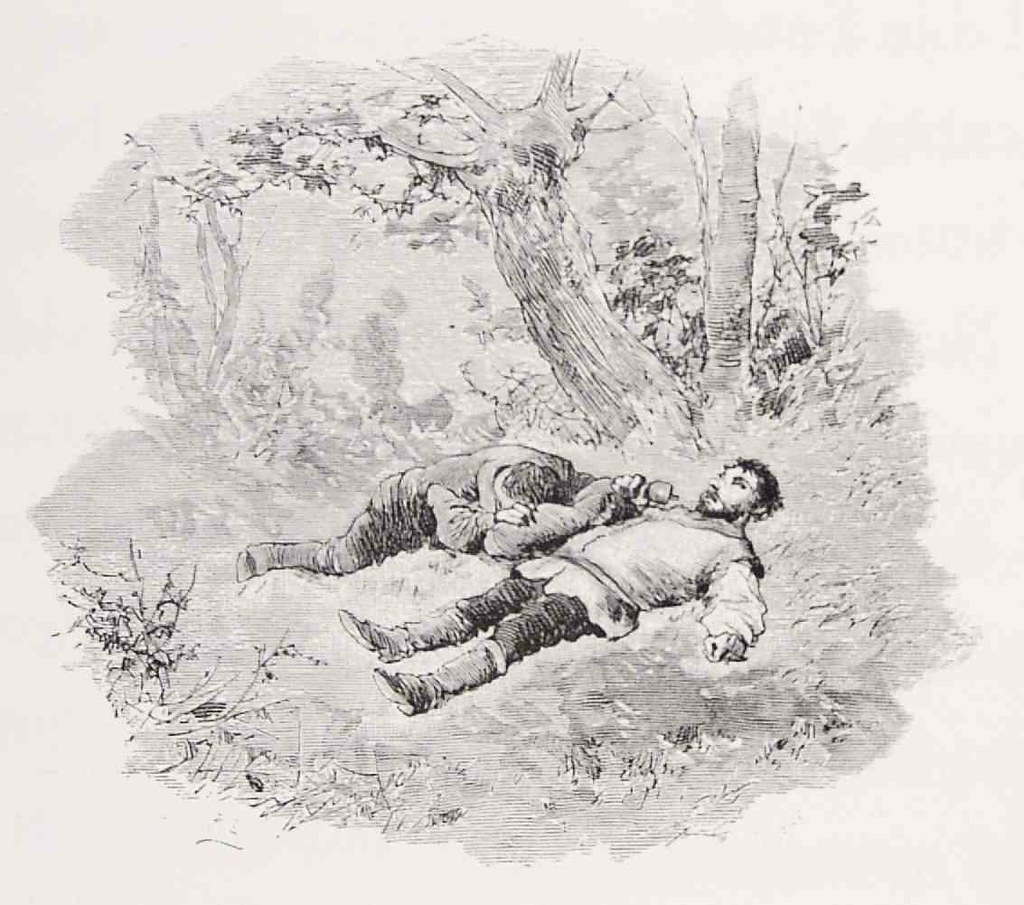

In short, the two good squires spoke so much and drank so much that only sleep could stop their tongues and allay their thirst, for it would have been impossible to take it away altogether; and so, with both of them holding on to the almost empty wineskin, and with mouthfuls of food half-chewed in their mouths, they fell asleep, which is where we shall leave them now in order to recount what befell the Knight of the Wood and the Knight of the Sorrowful Face.