Volume II (1615)

Regarding what transpired between Don Quixote and Doña Rodríguez, duenna to the duchess, as well as other events worthy of being recorded and remembered forever

A badly wounded Don Quixote, his face bandaged and marked not by the hand of God but by the claws of a cat, was far too dejected and melancholy at the misfortunes inherent in knight errantry. He did not go out in public for six days, and on one of those nights, when he was sleepless and awake, thinking about his misfortunes and his pursuit by Altisidora, he heard someone opening the door of his room with a key, and then he imagined that the enamored maiden was coming to assail his chastity and put him in a situation where he would fall short of the faith he was obliged to keep with his lady Dulcinea of Toboso.

“No,” he said in a voice that could be heard, believing what he had just imagined, “the greatest beauty on earth will not influence me to stop adoring the one I have engraved and impressed deep in my heart and at the very center of my being, no matter, my lady, if you are transformed into an uncouth peasant, or a nymph of the golden Tajo weaving cloth of gold and silk, or are being held by Merlin or Montesinos wherever they wish, for wherever you may be, you are mine, and wherever I go, I have been and shall be yours.”

The conclusion of these words and the opening of the door were all one. He stood on his bed, wrapped from head to toe in a yellow satin bedspread, a two-cornered beretta on his head, and his face and mustache bandaged: his face on account of the scratches, his mustache so that it would not droop and fall, and in this garb he seemed the most extraordinary phantom that anyone could imagine.

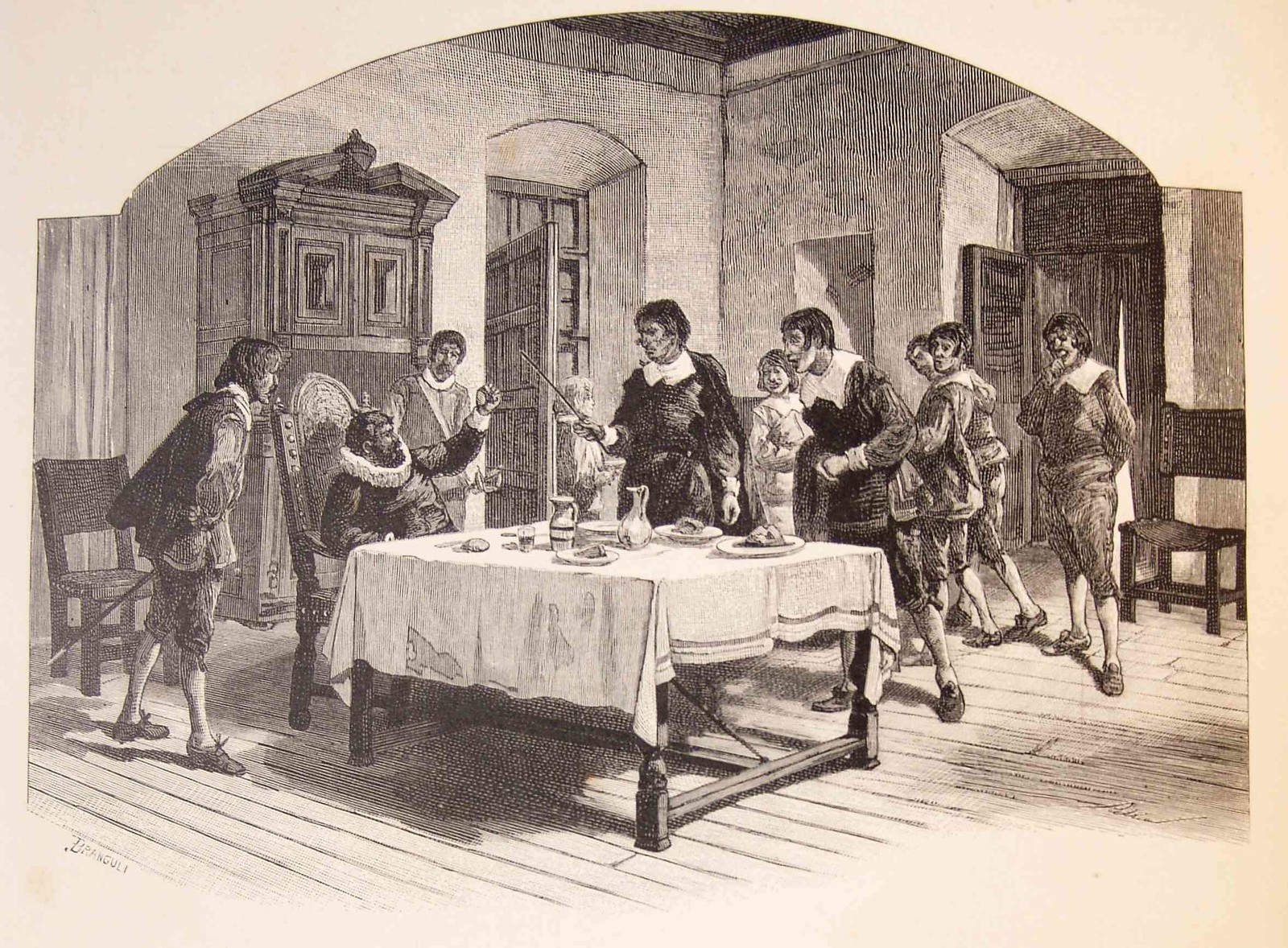

He fixed his eyes on the door, and where he expected to see the overwhelmed and lovesick Altisidora come in, he saw instead a most reverend duenna wearing white veils so long and intricate that they covered and enshrouded her from head to foot. In the fingers of her left hand she carried half a burning candle, and with her right hand she shadowed her face so that the light would not shine in her eyes, which were covered by very large spectacles. She stepped very softly and moved her feet very quietly.

Don Quixote looked down at her from his observation post, and when he saw her manner of dress and noticed her silence, he thought that a witch or a sorceress had come in that attire to commit some villainy against him, and he began very quickly to cross himself. The terrifying vision continued to approach, and when she reached the middle of the chamber, she raised her eyes and saw with what urgency Don Quixote was making the sign of the cross; and if he was fearful at the sight of her figure, she was terrified at seeing his, because as soon as she saw him, so high, and so yellow in the bedspread, and with the bandages that disfigured him, she screamed, saying:

“Jesus! What am I seeing?”

And she was so startled that she dropped the candle, and finding herself in the dark, she turned to leave, and in her fear she tripped on her skirts and fell with a great noise. A fearful Don Quixote began to say:

“I conjure thee, phantom, or whatever thou mayest be, to tell me what thou art and to tell me what it is that thou wantest of me. If thou art a soul in torment, tell me, and I shall do for thee all that is in my power, for I am a Catholic Christian and partial to doing good to everyone; for that reason I took on the order of knight errantry which I profess, whose exercise extends even to doing good to souls in purgatory.”

The dumbfounded duenna, who heard herself being conjured, associated Don Quixote’s fear with her own, and in a low and grieving voice she responded:

“Señor Don Quixote, if your grace happens to be Don Quixote, I am no phantom or vision or soul in purgatory, as your grace must have thought, but Doña Rodríguez, the duenna-of-honor to my lady the duchess, and I have come to your grace because I am in the sort of need your grace usually remedies.”

“Tell me, Señora Doña Rodríguez,” said Don Quixote, “by any chance has your grace come to act as a go-between? For I must tell you that I am not available to anyone, thanks to the peerless beauty of my lady Dulcinea of Toboso. In short, Señora Doña Rodríguez, I say that if your grace sets and puts aside all amorous messages, you may light your candle again, and come back, and we shall speak of anything you like and desire, except, as I have said, any invitation to the affections.”

“I, serve as anyone’s messenger, Señor?” responded the duenna. “Your grace does not know me very well; indeed, I have not yet reached so advanced an age that I resort to such foolishness, for, God be praised, I still have my soul in my body, and all my teeth and molars in my mouth except for a few that were taken by the catarrh, which is so common in this land of Aragón. But wait for me a moment, your grace, and I shall go out to light my candle and return in an instant to tell you of my cares, as if you were the one to remedy all the cares in the world.”

And without waiting for a reply, she left the room, where Don Quixote remained, calm and pensive, waiting for her; but then he had a thousand thoughts regarding this new adventure, and it seemed to him that he had behaved incorrectly and shown worse judgment by placing himself in danger of breaking the faith he had promised his lady, and he said to himself:

“Who knows if the devil, who is subtle and cunning, wants to deceive me now with a duenna when he has failed with empresses, queens, duchesses, marquises, and countesses? For I have often heard it said by many wise men that, if he can, he will give you a snub-nosed woman rather than one with an aquiline nose. And who knows whether this solitude, this opportunity, this silence, will awaken my sleeping desires and cause me, at this advanced age, to fall where I never have stumbled? In cases like this, it is better to flee than to wait for the battle. But I cannot be in my right mind, saying and thinking such nonsense, for it is not possible for a duenna in long white veils and spectacles to provoke or stimulate lascivious thoughts in the world’s most susceptible bosom. Can there be a duenna on earth whose flesh is chaste? Can there be a duenna on the planet who is not insolent, affected, and pretentious? Be gone, then, duennaesque horde, useless for any human pleasures! Oh, how wise the lady who, they say, had two figures of duennas with their spectacles and pincushions, as if they were doing needlework, at the end of her drawing room couch, and the statues did as much for the authority of the room as real duennas did!”

And saying this, he leaped out of bed, intending to close the door and not allow Señora Rodríguez to enter, but as he was about to close it, Señora Rodríguez returned, holding a lighted candle of white wax, and when she saw Don Quixote more closely, wrapped in the bedspread, with his bandages and his cap or beretta, she became afraid again, took two steps backward, and said:

“Is my safety assured, Señor Knight? Because I do not take it as a sign of modesty that your grace has gotten out of your bed.”

“I could very well ask the same question, Señora,” responded Don Quixote, “and so I ask if I shall be safe from assault and violation.”

“From whom or to whom, Señor Knight, do you ask for that assurance?” responded the duenna.

“From you and to you,” responded Don Quixote, “for I am not marble and you are not bronze, and it is not now ten in the morning but midnight, or even a little later, I imagine, and this is a chamber more hidden and secret than the cave where the traitorous and reckless Aeneas enjoyed the beautiful and compassionate Dido. But give me, Señora, your hand, for I wish no greater assurance than that of my own continence and modesty, and that offered by these most reverend veils.”

And having said this, he kissed her right hand and held it in his own, and she did the same, with the same ceremony.

Here Cide Hamete offers an aside and says that, by Mohammed, he would give the better cloak of two that he owns to see them holding and grasping each other as they walked from the door to the bed.

Don Quixote at last got into his bed, and Doña Rodríguez sat in a chair at some distance from the bed, not removing her spectacles or setting down the candle. Don Quixote concealed and hid himself completely, leaving only his face uncovered, and when the two had regained their composure, the first to break the silence was Don Quixote, saying:

“Now, Señora Doña Rodríguez, your grace can reveal and disclose all that is in your troubled heart and care-ridden soul, for it will be heard by my chaste ears and remedied by my compassionate deeds.”

“I do believe,” responded the duenna, “that from your grace’s gallant and pleasing presence one could expect only this Christian response. The fact, then, Señor Don Quixote, is that although your grace sees me sitting in this chair, in the middle of the kingdom of Aragón, and in the dress of an exhausted duenna in decline, I am a native of Asturias de Oviedo,530 and my lineage is crossed with many of the best in that province, but my bad luck, and the imprudence of my parents who became impoverished too soon, not knowing how or why, brought me to the court, in Madrid, and for their peace of mind and to avoid greater misfortunes, my parents arranged for me to do needlework in the service of a noblewoman; I want your grace to know that no one has ever outdone me in the hemstitch or needlepoint. My parents left me in service and returned home, and in a few years they left there and must have gone to heaven, because they were very good Catholic Christians. I was an orphan, and dependent on the miserable salary and grudging favors that maids like me receive at court; at this time, without any sort of encouragement from me, a squire of the house fell in love with me, a man somewhat advanced in years, bearded and imposing and, above all, as noble as the king because he was from the mountains.531 Our courtship was not so secret that it did not come to the attention of my lady, who, to avoid gossip and talk, married us with the approval and blessing of our Holy Mother Roman Catholic Church, and from our marriage a daughter was born, putting an end to what good fortune I had, not because I died in childbirth, for I delivered safely and on time, but because not long afterward my husband died of fright, and if I had time now to tell you about it, I know that your grace would be astounded.”

And at this she began to cry very piteously and said:

“Señor Don Quixote, your grace must forgive me, but I cannot help it, because every time I remember my poor husband my eyes fill with tears. Lord save me! With what authority did he carry my lady on the hindquarters of a powerful mule, as black as jet itself! For in those days they did not use coaches or saddles, as they do nowadays, and ladies rode behind their squires. This, at least, I must recount, so that you can see the breeding and manners of my good husband. Just as they were entering Calle Santiago in Madrid, which is rather narrow, a court magistrate, with two bailiffs riding in front of him, was coming out, and as soon as my good squire saw him, he turned the reins of the mule, indicating that he would turn back and accompany him.532 My lady, who was riding on the hindquarters of the mule, said in a low voice: ‘What are you doing, you miserable wretch? Have you forgotten that I am here?’ The magistrate, out of courtesy, pulled on the reins of his horse and said: ‘Señor, continue on your way: it is I who should accompany Señora Doña Casilda,’ for that was the name of my mistress.

My husband still persisted, with hat in hand, in trying to accompany the magistrate, seeing which my lady, full of anger and rage, took a thick needle, or it might have been a long hairpin, from its case, and stuck him in the back, so that my husband gave a great shout and twisted his body around, knocking my lady to the ground. Two of her lackeys hurried to pick her up, as did the magistrate and the bailiffs; the Guadalajara Gate, I mean the shiftless people loitering there, was in an uproar; my mistress left on foot, and my husband went to the house of a barber, saying that his innards had been pierced right through. My husband’s courtesy became the subject of so much talk that boys ran after him in the streets, and for that reason, and because he was somewhat shortsighted, my lady the duchess533 dismissed him, and I have no doubt that his grief over this is what caused his death. I was left a helpless widow, with a daughter to care for, whose beauty was growing like the ocean foam.

Finally, since I was known for fine needlework, my lady the duchess, who had recently married my lord the duke, offered to bring me, as well as my daughter, to this kingdom of Aragón, where the days passed, and my daughter grew and was endowed with all the graces in the world: she sings like a lark, dances court dances like a lightning flash and country dances like a whirlwind, reads and writes like a schoolmaster, and counts like a miser. I say nothing about her purity: running water is not purer, and now, if I remember correctly, she must be sixteen years, five months, and three days old, give or take a few.

In short, the son of a very rich farmer who lives in a village not very far from here, which belongs to my lord the duke, fell in love with my girl. The fact is that I don’t know how it happened, but they met, and promising to be her husband, he deceived my daughter, and now he refuses to keep his word; even though my lord the duke knows about it, because I myself have complained to him not once, but many times, and have asked him to order the farmer to marry my daughter, he ignores me and doesn’t want to listen to me, and the reason is that since the se-ducer’s father is so rich and lends him money, and sometimes stands as his guarantor when he gets into difficulties, he doesn’t want to anger or trouble him in any way.

And so, Señor, I would like your grace to take responsibility for righting this wrong, either by persuasion or by arms, for according to what everyone says, your grace was born into this world to redress grievances and right wrongs and come to the aid of those in need; your grace should keep in mind that my daughter is an orphan, and well-bred, and young, and possessed of all those gifts that I have mentioned to you, for by God and my conscience, of all the maidens that my mistress has, there is none that can even touch the sole of her shoe, and the one they call Altisidora, the one they consider the most elegant and spirited, can’t come within two leagues of my daughter. Because I want your grace to know, Señor, that all that glitters is not gold; this little Altisidora has more vanity than beauty, and more spirit than modesty, and besides, she’s not very healthy: she has breath so foul that you can’t bear to be near her even for a moment. And then, my lady the duchess…But I’d better be quiet, because they say that the walls have ears.”

“By my life, what is wrong with my lady the duchess, Señora Doña Rodríguez?” asked Don Quixote.

“With that oath,” responded the duenna, “I must respond truthfully to what I have been asked. Señor Don Quixote, has your grace seen the beauty of my lady the duchess, her complexion that resembles a smooth and burnished sword, her two cheeks of milk and carmine, the sun glowing on one and the moon on the other, and the elegance with which she treads, even scorns, the ground, so that it looks as if she were scattering health and well-being wherever she goes? Well, your grace should know that for this she can thank God, first of all, and then the two issues534 she has on her legs, which drain the bad humors that the doctors say fill her body.”

“Holy Mary!” said Don Quixote. “Is it possible that my lady the duchess has those drains? I would not believe it if discalced friars told me so, but since Señora Rodríguez says it, it must be true. But from such issues in such places there must flow not humors but liquid amber. Truly, now I believe that this incising of issues must be important for one’s health.”

As soon as Don Quixote had finished saying this, the doors of his room banged open, and Doña Rodríguez was so startled that the candle dropped from her hand, and the room was left like the inside of a wolf’s mouth, as the saying goes. Then the poor duenna felt her throat grasped so tightly by two hands that she could not cry out, and another person, with great speed, and without saying a word, raised her skirts, and with what appeared to be a slipper began to give her so many blows that it was pitiful; although Don Quixote was near her, he did not move from the bed, and he did not know what it could be, and he remained still and quiet, even fearing that the thrashing and the blows might be turned on him. And his was not an idle fear, for when they had left the duenna bruised and battered—she did not dare even to moan—the silent scourgers turned on Don Quixote and, stripping him of the sheet and bedspread, pinched him so hard and so often that he could not help but defend himself with his fists, all of this in the most remarkable silence. The battle lasted almost half an hour; the phantoms left, Doña Rodríguez picked up her skirts, and, groaning over her misfortune, went out the door without saying a word to Don Quixote, who, sorrowful and pinched, confused and thoughtful, was left alone, where we shall leave him, desiring to know which perverse enchanter had done this to him. But that will be told in due course, for Sancho Panza is calling us, and the harmonious order of the history requires that we respond.