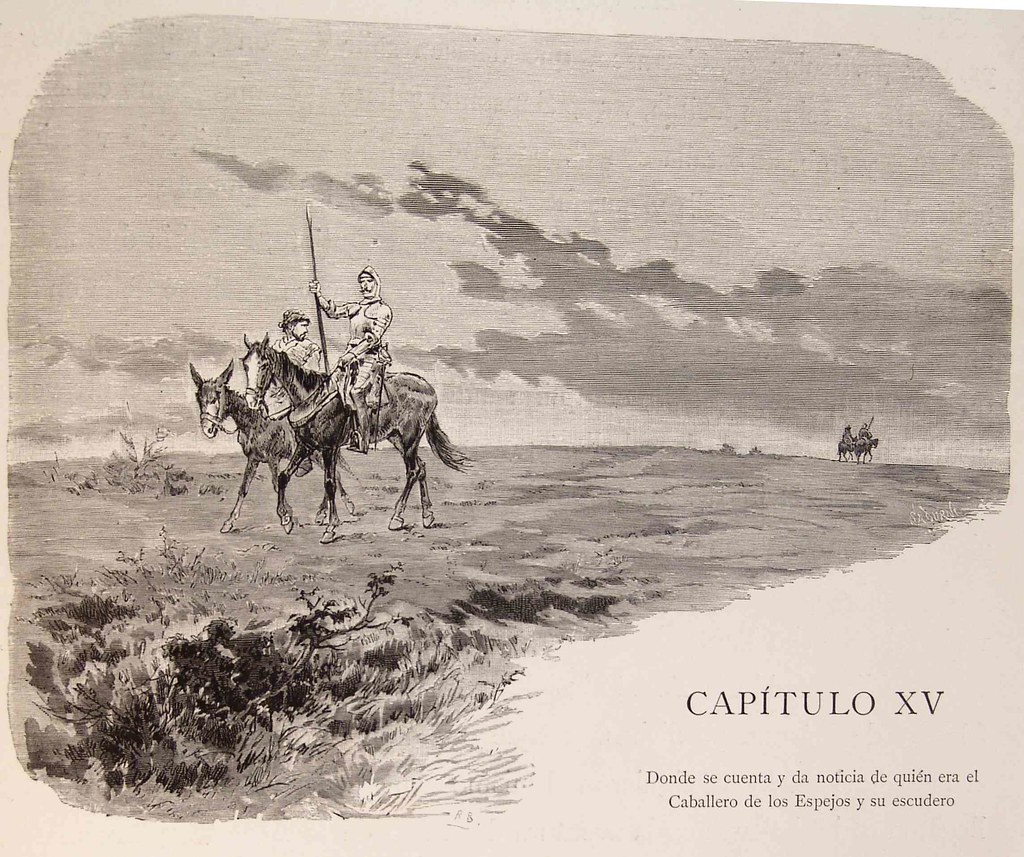

Volume II (1615)

Which recounts and relates the identity of the Knight of the Mirrors and his squire

Don Quixote was filled with contentment, pride, and vainglory at having achieved victory over so valiant a knight as he imagined the Knight of the Mirrors to be, and from his chivalric promise he hoped to learn if the enchantment of his lady was still in effect, since it was necessary for the conquered knight to return, under pain of no longer being a knight, to tell him what had transpired with her. But Don Quixote thought one thing and the Knight of the Mirrors thought another, for his only thought then was to find a place where he could apply a plaster, as has already been said.

And so, the history tells us that when Bachelor Sansón Carrasco advised Don Quixote to return to the chivalric undertakings he had abandoned, it was because he first had spoken privately with the priest and the barber regarding the steps that could be taken to prevail upon Don Quixote to remain quietly and peacefully at home and not be disturbed by ill-fated adventures; and the decision of this meeting was, by unanimous vote and the particular support of Carrasco, that they would allow Don Quixote to leave, since it seemed impossible to stop him, and that Sansón, as a knight errant, would meet him on the road and engage in combat with him, for there was no lack of reasons to fight, and he would vanquish him, on the assumption that this would be an easy thing to do, and it would be agreed and accepted that the vanquished would be at the mercy of the victor, and when Don Quixote had been vanquished, the bachelor-knight would order him to return to his village and his house and not leave again for two years, or until he had commanded otherwise; it was clear that the vanquished Don Quixote would undoubtedly obey in order not to contravene or disrespect the laws of chivalry, and it might be that in the time of his seclusion he would forget his illusions, or a worthwhile remedy would be found to cure his madness.

Carrasco agreed, and Tomé Cecial, Sancho Panza’s compadre and neighbor, and a cheerful, lighthearted man, volunteered to be his squire. Sansón armed himself in the manner described, and Tomé Cecial placed on his natural nose the false nose already referred to, so that his compadre would not recognize him when they met; they followed the same route taken by Don Quixote, and they almost arrived in time to take part in the adventure of the cart of Death. Finally, they met in the wood, where everything the prudent reader has just read happened to them, and if it had not been for Don Quixote’s extraordinary ideas that led him to believe the bachelor was not the bachelor, Señor Bachelor would have been forever incapable of receiving his licentiate’s degree, for he thought he would find birds and did not even find nests.

Tomé Cecial, who saw how badly their plans had turned out and how unfortunately their journey had ended, said to the bachelor:

“Certainly, Señor Sansón Carrasco, we’ve gotten what we deserved: it’s easy enough to think up and begin an enterprise, but most of the time it’s hard to end it. Don Quixote’s crazy, we’re sane, and he walks away healthy and laughing, while your grace is bruised and sad. So tell me now, who’s crazier: the man who’s crazy because he can’t help it or the man who chooses to be crazy?”

To which Sansón responded:

“The difference between those two madmen is that the one who can’t help it will always be mad, and the one who chooses can stop whenever he wants to.”

“Well, that’s true,” said Tomé Cecial. “I chose to be crazy when I decided to become your grace’s squire, and by the same token I want to stop now and go back home.”

“That may be convenient for you,” responded Sansón, “but if you think I’ll go back to mine before I’ve given Don Quixote a good beating, then you are sadly mistaken; I’m moved now not by the desire to help him recover his sanity, but by the desire for revenge; the terrible pain in my ribs does not allow me to speak more piously.”

The two men conversed in this manner until they reached a village where they happened to find a bonesetter[1] who cured the unfortunate Sansón. Tomé Cecial turned back and left him, and Sansón remained behind to imagine his revenge, and the history speaks of him again at the proper time, but it joyfully returns now to Don Quixote.

- Cervantes uses the word 'algebrist' for bonesetter because 'Algebra is the art of concerting disjointed and broken bones'. This Cervantine use of the word algebra has a nice story related to a mathematician by the name of Mohamed Ibn-Musa Al-Kowarizmi, who lived and worked under the protection of the caliphate of Al-Mamun (809-833), successor of the caliph Harun Al-Raschid, the latter made a character for posterity in The Thousand and One Nights. Al-Kowarizmi's name survived time by those strange twists of languages: Al-Kowarizmi derived in the word algorithm; this is what we understand as a set of rules for the solution of specific problems. Al-Kowarizmi's main work is, perhaps, the first great recipe book for solving equations of the type we learn in high school. It is precisely the title of this work, Al-jabr wa'l muqabalah that gives rise to the term algebra (al-jabr) and its meaning is implicit in the preface of the book: al-jabr is 'completion' or 'concertation' (we assume that of terms in an equation) and muqabalah is 'reduction or balancing' (in reference to the cancellation of equal terms on opposite sides of the equality). ↵