Volume II (1615)

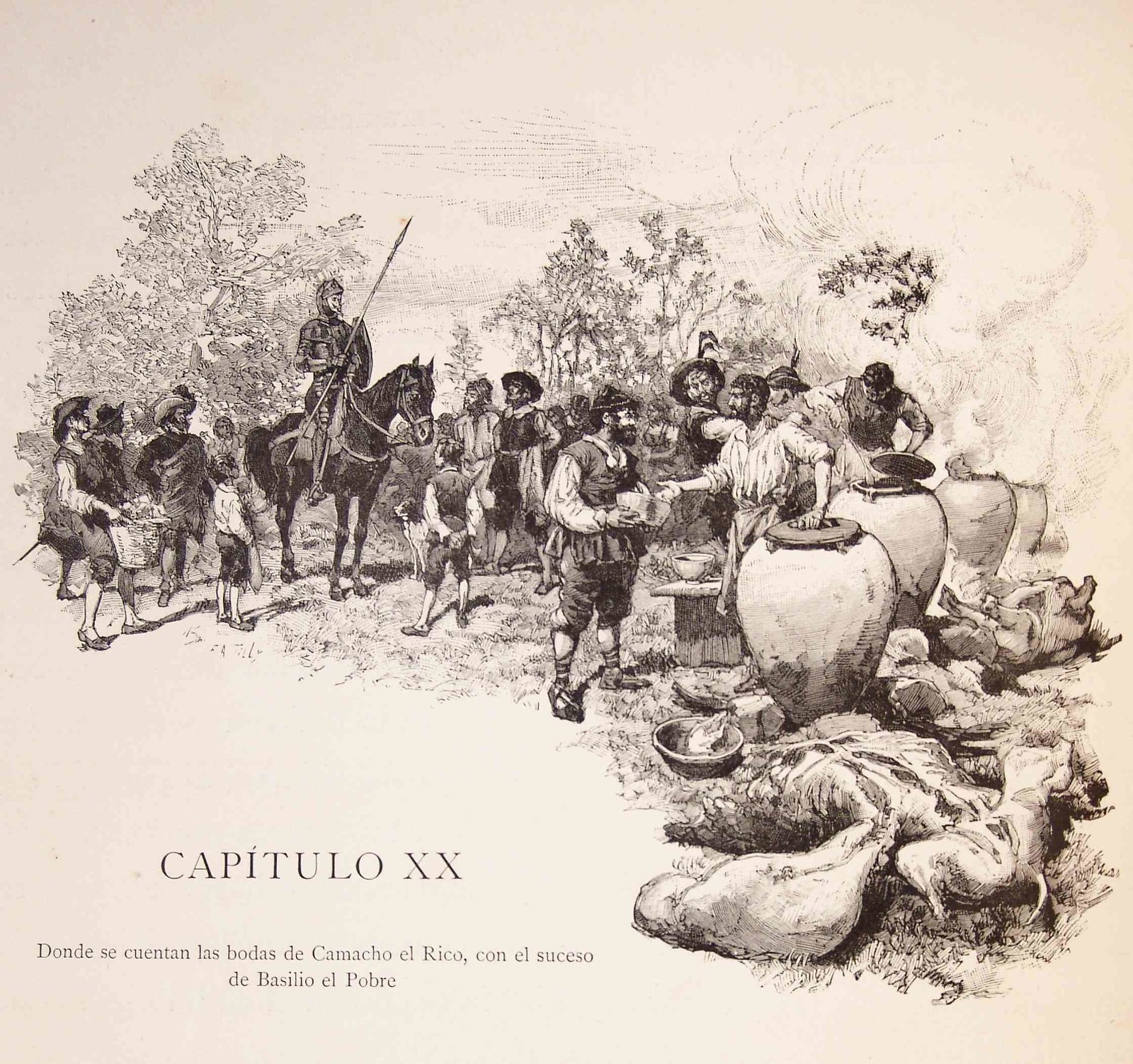

Which recounts the wedding of rich Camacho, as well as what befell poor Basilio

No sooner had fair-complexioned dawn allowed bright Phoebus, with the ardor of his burning rays, to dry the liquid pearls of her golden tresses, than Don Quixote, shaking idleness from his limbs, rose to his feet and called to his squire, Sancho, who was still snoring; and Don Quixote saw this, and before he woke him he said:

“O thou, more fortunate than all those who live on the face of the earth, for thou dost not envy nor art thou envied, and thou sleepest with a tranquil spirit, and thou art not pursued by enchanters, nor art thou alarmed by enchantments! Thou sleepest, I say it again and shall say it a hundred times more, without jealousy of thy lady keeping thee continually awake, nor thoughts of how to pay the debts thou owest, nor what thou must do to feed thyself and thy small, anguished family for another day. Ambition doth not disturb thee, nor doth the vain pomp of the world trouble thee, for the limits of thy desires extendeth not beyond caring for thy donkey; thou hast placed care for thine own person on my shoulders, a weight and a burden that nature and custom hath given to masters. The servant sleepeth, and the master standeth watch, thinking of how he may sustain him, and improve him, and grant him favors. The anguish of seeing the sky turning to bronze and not giving succor to the earth with needed dew doth not afflict the servant but the master, who must sustain in barrenness and hunger the one who served in fertility and plenty.”

Sancho did not respond to any of this because he was asleep, and he would not have awakened very quickly if Don Quixote, with the blunt end of his lance, had not brought him back to consciousness. He awoke, finally, sleepy and lazy, and turning his head in every direction, he said:

“Coming from the direction of that bower, if I’m not mistaken, there’s an aroma that smells much more like a roasted side of bacon than reeds and thyme: by my faith, weddings that begin with smells like this must be plentiful and generous.”

“Enough, you glutton,” said Don Quixote. “Come, we shall go to this ceremony to see what the scorned Basilio will do.”

“No matter what he does, what he’d like,” responded Sancho, “is not to be poor and to marry Quiteria. He doesn’t have a cuarto and he wants to rise up above the clouds? By my faith, Señor, I think a poor man should be content with whatever he finds and not go asking for the moon. I bet an arm that Camacho can bury Basilio in reales, and if that’s true, as it must be, Quiteria would be a fool to give up the fine gifts and jewels that Camacho must have given her already, and still can give her, for the way Basilio hurls the bar and fences. A good throw and some nice swordplay won’t get you a half-liter of wine at the tavern. Talents and skills that can’t be sold are fine for Count Dirlos,387 but when those talents fall to somebody who has good money, then that’s the life I’d like to have. With a good foundation you can build a good building, and the best foundation and groundwork in the world is money.”

“For the love of God, Sancho,” said Don Quixote, “that’s enough of your harangue. I really believe that if you were allowed to go on with the ones you are constantly beginning, you would not have time to eat or sleep: you would spend all of it talking.”

“If your grace had a good memory,” replied Sancho, “you’d remember the provisions of our agreement before we left home this last time: one of them was that you’d have to let me talk all I wanted as long as I didn’t say anything against my neighbor or your grace’s authority, and so far it seems to me I haven’t disobeyed that provision.”

“I do not remember, Sancho,” responded Don Quixote, “any such provision, and since that is so, I want you to be quiet and come along now; the instruments we heard last night again gladden the valleys, and no doubt the wedding will be celebrated in the coolness of the morning, not in the heat of the afternoon.”

Sancho did as his master commanded and placed the saddle on Rocinante and the packsaddle on the donkey; the two men mounted, and at an unhurried pace, they rode under the bower.

The first thing that appeared before Sancho’s eyes was an entire steer on a roasting spit made of an entire elm; and in the fire where it was to roast, a fair-size mountain of wood was burning, and six pots that were placed around the fire were not made in the common mold of other pots, because these were six huge cauldrons, each one large enough to hold the contents of an entire slaughterhouse: they contained and enclosed entire sheep, which sank out of view as if they were doves; the hares without their skins and the chickens without their feathers that were hanging from the trees, waiting to be buried in the cauldrons, were without number; the various kinds of fowl and game hanging from the trees to cool in the breeze were infinite.

Sancho counted more than sixty wineskins, each one holding more than two arrobas, 388 and all of them filled, as was subsequently proven, with excellent wines; there were also mounds of snowy white loaves of bread, heaped up like piles of wheat on the threshing floor; cheeses, crisscrossed like bricks, formed a wall; and two kettles of oil larger than a dyer’s vats were used to fry rounds of dough, which were then removed with two strong paddles and plunged into another kettle filled with honey that stood nearby.

The cooks, male and female, numbered more than fifty, all of them devoted, diligent, and contented. Twelve small, tender suckling pigs were sewn into the expanded belly of the steer to give it flavor and make it tender. The various spices seemed to have been bought not by the pound but by the arroba, and all of them were clearly visible in a large chest. In short, the provisions for the wedding were rustic, but so abundant they could have fed an army.

Sancho Panza observed everything, and contemplated everything, and felt affection for everything. First, his desire was captivated and conquered by the cauldrons, from which he gladly would have filled a medium-size pot; then his affections were won over by the wineskins; finally, the fruits of the skillet, if one could call the big-bellied kettles skillets; and so, when he could bear it no longer, and it was not in his power to do anything else, he approached one of the diligent cooks and in courteous and hungry terms asked to be allowed to dip a crust of bread into one of those cauldrons. To which the cook responded:

“Brother, thanks to rich Camacho, hunger has no jurisdiction today. Dismount and see if you can find a ladle, and skim off a chicken or two, and hearty appetite to you.”

“I don’t see one,” responded Sancho.

“Wait,” said the cook. “Lord save me, but what a squeamish, fussy fellow you must be!”

And having said this, he seized a pot and dipped it into one of the cauldrons, then took out three chickens and two geese and said to Sancho:

“Eat, my friend, and break your fast with these skimmings until it’s time to eat.”

“I don’t have anything to put them in,” responded Sancho.

“Then take everything, the pot and all,” said the cook, “for the riches and the happiness of Camacho will overlook that.”

While Sancho was engaged in these matters, Don Quixote watched as some twelve farmers, dressed in their best holiday clothes and mounted on twelve beautiful mares decked out in rich and colorful rustic trappings, with a good number of bells on the breast straps of their harnesses, rode under the bower; in an orderly troop they galloped not once but many times around the meadow, joyfully crying and shouting:

“Long live Camacho and Quiteria! He’s as rich as she’s fair, and she’s the fairest in the world!”

Hearing which, Don Quixote said to himself:

“It certainly seems that they have not seen my Dulcinea of Toboso, for if they had, they would restrain their praises of Quiteria.”

A short while later, many different groups of dancers began to come under the bower, among them one performing a sword dance with twenty-four young men of gallant and spirited appearance, all dressed in thin white linen and wearing head scarves of fine, multicolored silk; one of the men mounted on mares asked their leader, an agile youth, if any of the dancers had been hurt.

“So far, thank God, nobody’s been hurt: we’re all fine.”

And then he began to wind his way among his companions, twisting and turning with so much skill that although Don Quixote had seen many such dances, he had never seen one as good as this.

He also liked another group that came in, composed of beautiful young maidens, none younger than fourteen, none older than eighteen, all dressed in fine green cloth, their hair partly braided and partly hanging loose, and so blond it could compete with the rays of the sun; and in their hair they wore garlands made of jasmine, roses, amaranth, and honeysuckle. They were led by a venerable old man and an ancient matron, more agile and nimble than their years would lead one to expect. Their music was played by a Zamoran bagpipe, and the maidens, with modesty in their eyes and on their faces, and with agility in their feet, showed themselves to be the best dancers in the world.

Behind them came another troop in an ingenious dance, the kind that is called a spoken dance. It consisted of eight nymphs, divided into two lines: at the head of one line was the god Cupid, and at the head of the other, Interest, the former adorned with wings, a bow, and a quiver of arrows, the latter dressed in richly colored silks and gold. The nymphs who followed Love had their names, written on white parchment in large letters, on their backs. Poetry was the name of the first, Discretion the name of the second, the third was called Good Lineage, and the fourth Valor. Those who followed Interest were identified in the same fashion: Liberality was the name of the first, Gifts the name of the second, the third was called Treasure, and the fourth Peaceful Ownership. At the head of all of them came a wooden castle, drawn by four savages dressed in ivy and green-dyed hemp and looking so natural they almost frightened Sancho. On the main facade of the castle, and on all four of its sides, was written The Castle of Caution. Their music was played on the timbrel and flute by four skilled musicians.

Cupid began the dance, and having completed two figures, he raised his eyes and shot an arrow at a maiden standing on the parapets of the castle, saying:

I am a god most powerful

in the air and on the land

and the wide, wind-driven sea,

and in the fiery pit

and the fearful hell it contains.

Fear’s something I’ve never known;

whatever I wish I can do,

though it may well be impossible;

in the realm of the possible I rule,

and give and take away at will.

He finished the strophe, shot an arrow over the castle, and returned to his place. Then Interest came forward and executed another two figures; the timbrels fell silent, and he said:

I am mightier than Love,

though it is Love who guides me;

I am of the finest stock,

the best known and the noblest,

that heaven breeds on earth.

I am Interest, and for my sake

few men do the deeds they should,

though deeds sans me are miracles;

I swear my devotion to you

forever, world without end, amen.

Interest stepped back, Poetry came forward, and after performing her figures as the others had, she turned her eyes toward the maiden of the castle and said:

In conceits most sweet and high,

noble, solemn, and discreet,

gentle Poetry, my lady,

sends her soul to you in lines

found in a thousand new sonnets.

If my pleas and constant prayers

do not weary you, your fortune,

envied by so many damsels,

will be raised on high by me,

to the Circle of the Moon.

Poetry moved away, and from the side where Interest stood, Liberality stepped forward, performed her figures, and said:

Liberality is the name

of giving that shuns th’ extremes

of either prodigality

or its opposite, th’ unwilling

hand of a miserly soul.

But, in order to praise you,

today I shall be prodigal,

and though a vice, it is honored

from a heart that is enamored,

and in giving shows its love.

In this fashion all the dancers in the two bands came forward and then withdrew, and each one performed her figures and said her verses, some of them elegant and some ridiculous, but Don Quixote could retain in his memory—which was very good—only those that have been cited; then all the dancers mingled, forming pairs and then separating with gentle grace and ease, and when Love passed in front of the castle, he shot his arrows into the air, but Interest broke gilded money boxes against it.

Finally, after having danced for some time, Interest took out a large bag made of the skin of a big Roman cat,389 which seemed to be full of coins, and threw it at the castle, and at the impact the boards fell apart and collapsed, leaving the maiden exposed and without any defenses. Interest approached with the dancers in his group, put a long gold chain around her neck, and pretended to seize and subdue her and make her his prisoner; when Love and his companions saw this, they moved to free her, and all these displays were made to the sound of the timbrels as they danced and twirled in harmony. The savages imposed peace when they quickly set up and put together again the boards of the castle, and the maiden went back inside, concluding the dance that had been watched with great pleasure by the spectators.

Don Quixote asked one of the nymphs who had composed and directed it. She responded that it was a cleric, a beneficiary from the village who had a great talent for these kinds of inventions.

“I would wager,” said Don Quixote, “that this beneficiary or bachelor must be more of a friend to Camacho than to Basilio, and that he is more inclined to writing satires than to saying his prayers at vespers. How well he has incorporated into the dance Basilio’s skills and Camacho’s wealth!”

Sancho Panza, who heard everything, said:

“My cock’s king;390 I’m on Camacho’s side.”

“In short,” said Don Quixote, “it seems clear, Sancho, that you are a peasant, the kind who shouts, ‘Long live whoever wins!’”

“I don’t know what kind I am,” responded Sancho, “but I do know that I’d never get such fine skimmings from Basilio’s pots as I’ve gotten from Camacho’s.”

And he showed him the pot full of geese and chickens, and seizing one of them, he began to eat with great verve and enthusiasm, saying:

“To hell with Basilio’s talents! You’re worth what you have, and what you have is what you’re worth. There are only two lineages in the world, as my grandmother used to say, and that’s the haves and the have-nots, though she was on the side of having; nowadays, Señor Don Quixote, wealth is better than wisdom: an ass covered in gold seems better than a saddled horse. And so I say again that I’m on the side of Camacho, whose pots are overflowing with geese and chickens, hares and rabbits, while Basilio’s, if they ever show up, and even if they don’t, won’t hold anything but watered wine.”

“Have you finished your harangue, Sancho?” said Don Quixote.

“I must have,” responded Sancho, “because I see that your grace is bothered by it; if you hadn’t cut this one short, I could have gone on for another three days.”

“May it please God, Sancho,” replied Don Quixote, “that I see you mute before I die.”

“At the rate we’re going,” responded Sancho, “before your grace dies I’ll be chewing on mud, and then maybe I’ll be so mute I won’t say a word till the end of the world or, at least, until Judgment Day.”

“Oh, Sancho, even if that should happen,” responded Don Quixote, “your silence will never match all that you have said, are saying, and will say in your lifetime! Furthermore, it seems likely in the natural course of events that the day of my death will arrive before yours, and so I think I shall never see you mute, not even when you are drinking, or sleeping, which is what I earnestly desire.”

“By my faith, Señor,” responded Sancho, “you mustn’t trust in the fleshless woman, I mean Death, who devours lamb as well as mutton; I’ve heard our priest say that she tramples the high towers of kings as well as the humble huts of the poor. This lady is more powerful than finicky; nothing disgusts her, she eats everything, and she does everything, and she crams her pack with all kinds and ages and ranks of people. She’s not a reaper who takes naps; she reaps constantly and cuts the dry grass along with the green, and she doesn’t seem to chew her food but wolfs it down and swallows everything that’s put in front of her, because she’s as hungry as a dog and is never satisfied; and though she has no belly, it’s clear that she has dropsy and is always thirsty and ready to drink down the lives of everyone living, like somebody drinking a pitcher of cold water.”

“Enough, Sancho,” said Don Quixote at this point. “Stop now before you fall, for the truth is that what you have said about death, in your rustic terms, is what a good preacher might say. I tell you, Sancho, with your natural wit and intelligence, you could mount a pulpit and go around preaching some very nice things.”

“Being a good preacher means living a good life,” responded Sancho, “and I don’t know any other theologies.”

“You do not need them,” said Don Quixote, “but I cannot understand or comprehend how, since the beginning of wisdom is the fear of God, you, who fear a lizard more than you fear Him, can know so much.”

“Señor, your grace should pass judgment on your chivalries,” responded Sancho, “and not start judging other people’s fear or bravery, because I fear God as much as the next man. And your grace should let me eat up these skimmings; all the rest is idle words, and we’ll have to account for those in the next world.”

And saying this, he resumed the assault on his pot with so much gusto that he awoke the appetite of Don Quixote, who no doubt would have helped him if he had not been hindered by what must be recounted below.