Volume II (1615)

Regarding matters that Benengeli says will be known to the reader if he reads with attention

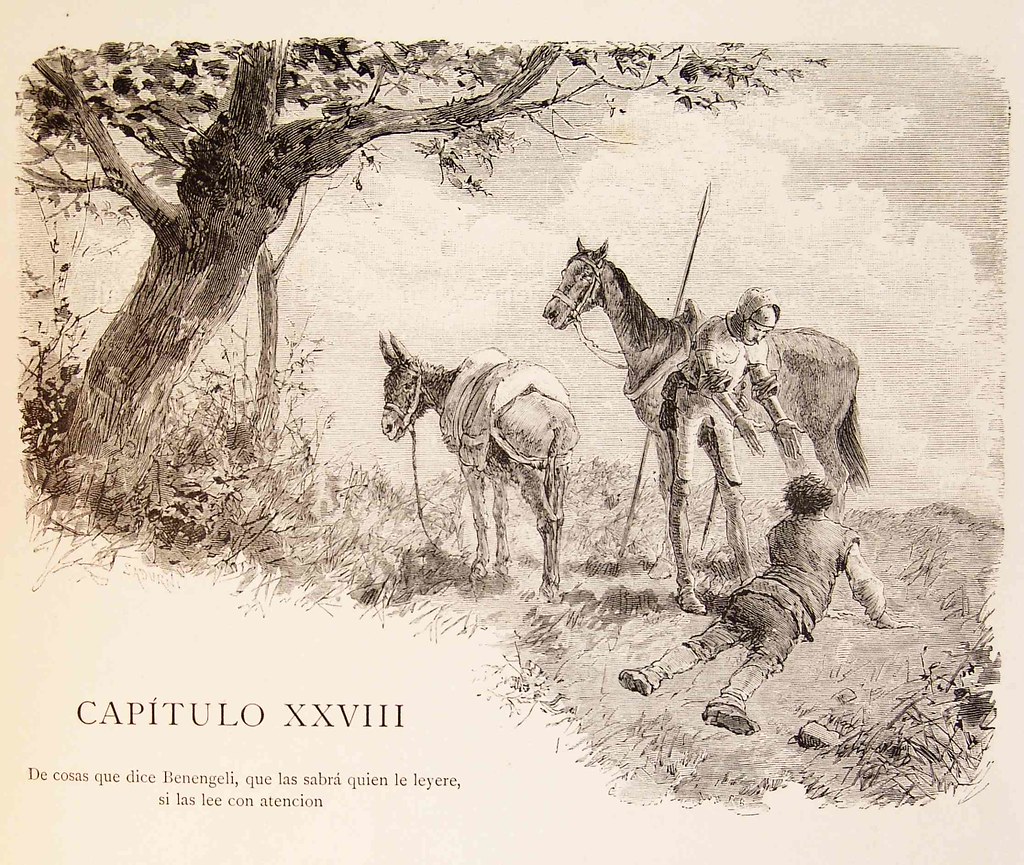

When the brave man flees, trickery is revealed, and the prudent man waits for a better opportunity. This truth was proved in Don Quixote, who yielded to the fury of the village and the evil intent of the enraged squadron and fled, not thinking of Sancho or the danger in which he left him, and rode the distance he thought sufficient to ensure his safety. Sancho followed, lying across his donkey, as has been related. When he had regained consciousness he overtook Don Quixote, and when he did, Sancho dropped off the donkey at Rocinante’s feet, perturbed, bruised, and battered. Don Quixote dismounted to tend to the squire’s wounds, but since he found him sound from head to foot, with some anger he said:

“It was an evil hour when you learned how to bray, Sancho!437 And when did you decide it would be a good idea to mention rope in the house of the hanged man? When braying is the music, what counterpoint can there be except a beating? Give thanks to God, Sancho, that even though they made the sign of the cross over you with a stick, they did not cut a per signum crucis 438 on your face.”

“I’m not about to respond,” responded Sancho, “because it seems to me I’m talking with my back. Let’s mount and leave this place, and I’ll silence my braying, but I won’t stop saying that knights errant run away and leave their good squires beaten to a pulp or ground up like grain and in the power of their enemies.”

“Withdrawal is not flight,” responded Don Quixote, “because you should know, Sancho, that valor not founded on the base of prudence is called recklessness, and the deeds of the reckless are attributed more to good fortune than to courage. And so I confess that I withdrew, but not that I fled, and in this I have imitated many valiant men who have waited for a better moment; the histories are full of such cases, but since they would not be to your advantage or my taste, I shall not recount them to you now.”

By now Sancho had mounted his donkey, with the assistance of Don Quixote, who then mounted Rocinante, and slowly they rode toward a stand of poplars that appeared about a quarter of a league distant. From time to time Sancho heaved some very deep sighs and mournful groans, and when Don Quixote asked the cause of such bitter feeling, he responded that from the base of his spine to the back of his neck he was in so much pain that it was driving him mad.

“The cause of this pain no doubt must be,” said Don Quixote, “that since the staff they used to beat you was long and tall, it hit the length of your back, which is where the parts that pain you are located; if it had hit more of you, more of you would be in pain.”

“By God,” said Sancho, “your grace has cleared up a great doubt, and said it so nicely, too! Lord save us! Was the cause of my pain so hidden that you had to tell me I hurt where the staff hit me? If my ankles hurt, there might be a reason to try and guess why, but guessing that I hurt where I was beaten isn’t much of a guess. By my faith, Señor Master, other people’s troubles don’t matter very much, and every day I learn something else about how little I can expect from being in your grace’s company, because if you let them beat me this time, then a hundred more times we’ll be back to the old tossings in a blanket and other tricks like that, and if it was my back now, the next time it’ll be my eyes. I’d be much better off, but I’m an idiot and will never do anything right in my life, but I’d be much better off, and I’ll say it again, if I went back home to my wife and children and supported her and brought them up with whatever it pleased God to give me, instead of following after your grace on roads that have no destination, and byways and highways that lead nowhere, drinking badly and eating worse. And sleeping! Brother squire, you can count on seven feet of ground, and if you want more, take another seven, for it’s all up to you, and you can stretch out to your heart’s content; all I hope is that I can see the first man who put the finishing touches on knight errantry burned and ground into dust, or at least the first one who wanted to be squire to the great fools that all knights errant in the past must have been. I won’t say anything about those in the present; since your grace is one of them, I respect them, and I know that your grace knows a point or two more than the devil in all you say and think.”

“I would make a wager with you, Sancho,”439 said Don Quixote. “Now that you are speaking and no one is restraining you, you have no pains anywhere in your body. Speak, my friend, and say everything that comes to your mind and your mouth; in exchange for your not having any pains, I shall consider the irritation your impertinence causes me as pleasure. And if you so fervently desire to return to your house and wife and children, God forbid that I do anything to stop you; you have my money; calculate how long it has been since we left our village this third time, and calculate what you can and should earn each month, and pay yourself a salary.”

“When I served Tomé Carrasco,” responded Sancho, “the father of Bachelor Sansón Carrasco, and your grace knows him very well, I earned two ducados a month, and food besides; with your grace I don’t know what I should earn, though I know that the squire of a knight errant has more work than a man who serves a farmer, because when we serve farmers, no matter how much we work during the day, and no matter what bad things happen to us, at night we eat stew and sleep in beds, which I haven’t done since I started serving your grace. Except for the short time we were in Don Diego de Miranda’s house, and the outing I had with the skimmings I took from Camacho’s pots, and the way I ate and drank and slept in Basilio’s house, all the rest of the time I’ve slept on the hard ground, outside, exposed to what they call the inclemencies of heaven, eating crumbs of cheese and crusts of bread and drinking water from streams or springs or whatever we find in those out-of-the-way places where we travel.”

“I confess,” said Don Quixote, “that everything you say, Sancho, is true. In your opinion, how much more should I give you than Tomé Carrasco did?”

“In my opinion,” said Sancho, “if your grace added two reales more a month, I’d think I was well-paid. This is the salary for my work, but as far as satisfying your grace’s word and promise to make me governor of an ínsula, it would be fair to add another six reales, and that would be a total of thirty.”

“Very well,” replied Don Quixote, “and in accordance with the salary you have indicated, it has been twenty-five days since we left our village: calculate, Sancho, the rate times the amount, and see what I owe you, and pay yourself the money, as I have said.”

“Oh, Lord,” said Sancho, “your grace is very much mistaken in this count, because in the matter of the promise of the ínsula, you have to count from the day your grace promised it to me until this very moment.”

“Well, Sancho, how long ago did I promise it to you?” said Don Quixote.

“If I remember correctly,” responded Sancho, “it must be more than twenty years, give or take three days.”

Don Quixote gave himself a great slap on the forehead and began to laugh very heartily, and he said:

“My travels in the Sierra Morena or in the course of all our sallies took barely two months, and you say, Sancho, that I promised you the ínsula twenty years ago? Now I say that you want to use all my money for your salary, and if this is true, and it makes you happy, I shall give it all to you, and may it do you good; in exchange for finding myself without so bad a squire, I shall enjoy being poor and not having a blanca. But tell me, you corrupter of the squirely rules of knight errantry, where have you seen or read that any squire of a knight errant has engaged his master in ‘You have to give me this amount plus that amount every month for serving you’? Set sail, set sail, scoundrel, coward, monster, for you seem to be all three, set sail, I say, on the mare magnum 440 of their histories, and if you find that any squire has said, or even thought, what you have said here, I want you to fasten it to my forehead and then you can pinch my face four times. Turn the reins or halter of your donkey, and go back to your house, because you will not take another step with me. O bread unthanked! O promises misplaced! O man more animal than human! Now, when I intended to place you in a position where, despite your wife, you would be called Señor, now you take your leave? Now you go, when I had the firm and binding intention of making you lord of the best ínsula in the world? In short, as you have said on other occasions, there is no honey…441 You are a jackass, and must be a jackass, and will end your days as a jackass, for in my opinion, your life will run its course before you accept and realize that you are an animal.”

Sancho stared at Don Quixote as he was inveighing against him and felt so much remorse that tears came to his eyes, and in a weak and mournful voice he said:

“Señor, I confess that for me to be a complete jackass, all that’s missing is my tail; if your grace wants to put one on me, I’ll consider it well-placed, and I’ll serve you like a donkey for the rest of my days. Your grace should forgive me, and take pity on my lack of experience, and remember that I know very little, and if I talk too much, it comes more from weakness than from malice, and to err is human, to forgive, divine.”

“I would be amazed, Sancho, if you did not mix some little proverb into your talk. Well, then, I forgive you as long as you mend your ways and from now on do not show so much interest in your own gain, but attempt to take heart, and have the courage and valor to wait for my promises to be fulfilled, for although it may take some time, it is in no way impossible.”

Sancho responded that he would, although it would mean finding strength in weakness.

Saying this, they entered the stand of trees, and Don Quixote settled down at the foot of an elm, and Sancho at the foot of a beech, for these trees, and others like them, always have feet but not hands. Sancho spent a painful night, because he felt the beating more in the night air, and Don Quixote spent the night in his constant memories; even so, their eyes closed in sleep, and at daybreak they continued on their way, looking for the banks of the famous Ebro, where something occurred that will be recounted in the following chapter.