Volume II (1615)

Regarding what befell Don Quixote with a beautiful huntress

Knight and squire returned to their animals feeling rather melancholy and out of sorts, especially Sancho, for whom touching their store of money touched his very soul, since it seemed to him that taking anything away from it meant taking away the apple of his eye. Finally, without saying a word, they mounted and rode away from the famous river, Don Quixote sunk deep in thoughts of love, and Sancho in those of his increased revenues, which at the moment he seemed very far from obtaining; although he was a fool, he understood very well that all or most of his master’s actions were mad, and he was looking for an opportunity to tear himself away and go home without engaging his master in explanations or leavetakings, but Fortune ordained that matters should take a turn contrary to his fears.

It so happened, then, that the next day, as the sun was setting and they were riding out of a wood, Don Quixote cast his eye upon a green meadow, and at the far end he saw people, and as he drew near he realized that they were falconers.444 He came closer, and among them he saw a graceful lady on a snow white palfrey or pony adorned with a green harness and a silver sidesaddle. The lady was also dressed in green, so elegantly and richly that she seemed the very embodiment of elegance. On her left hand she carried a goshawk, which indicated to Don Quixote that she was a great lady and probably the mistress of all the other hunters, which was true, and so he said to Sancho:

“Run, Sancho my friend, and tell the lady with the goshawk, who is on the palfrey, that I, the Knight of the Lions, kiss the hands of her great beauty, and if her highness gives me permission to do so, I shall kiss her hands myself and serve her to the best of my ability and to the extent her highness commands. And be careful, Sancho, how you speak, and be careful not to inject any of your proverbs into the message.”

“You take me for an injecter!” responded Sancho. “You say that to me! This isn’t the first time in my life, you know, that I’ve carried messages to high and mighty ladies!”

“Except for the one you carried to the lady Dulcinea,” replied Don Quixote, “I do not know that you have ever carried another, at least not in my service.”

“That is true,” responded Sancho, “but if you pay your debts, you don’t worry about guaranties, and in a prosperous house supper’s soon on the stove; I mean that nobody has to tell me things or give me any advice: I’m prepared for anything, and I know something about everything.”

“I believe you, Sancho,” said Don Quixote. “Go, then, and may God go with you.”

Sancho left at a trot, urging his donkey on to a faster pace than usual, and when he reached the beautiful huntress he dismounted, kneeled before her, and said:

“Beautiful lady, that knight over there, called The Knight of the Lions, is my master, and I’m his squire, called Sancho Panza at home. This Knight of the Lions, who not long ago was called The Knight of the Sorrowful Face, has sent me to ask your highness to have the goodness to give permission for him, with your agreement, approval, and consent, to put his desire into effect, which is, as he says and I believe, none other than to serve your lofty highness and beauty, and by giving it, your ladyship will do something that redounds to your benefit, and from it he’ll receive a most notable favor and happiness.”

“Indeed, good squire,” responded the lady, “you have delivered your message with all the pomp and circumstance that such messages demand. Rise up from the ground; it is not right for the squire of so great a knight as the Knight of the Sorrowful Face, about whom we have heard so much, to remain on his knees: arise, friend, and tell your master that he is very welcome to serve me and my husband, the duke, on a country estate we have nearby.”

Sancho stood, amazed by the beauty of the good lady and by her great breeding and courtesy, and especially by her saying that she had heard of his master, the Knight of the Sorrowful Face, and if she did not call him the Knight of the Lions, it must have been because he had taken the name so recently. The duchess, whose title was still unknown, asked him:

“Tell me, my dear squire: this master of yours, isn’t he the one who has a history published about him called The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, and isn’t the mistress of his heart a lady named Dulcinea of Toboso?”

“He’s the very one, Señora,” responded Sancho, “and that squire of his who is, or ought to be, in that history, the one named Sancho Panza, is me, unless I was changed for another in the cradle, I mean the printing press.”

“All of this makes me very happy,” said the duchess. “Go, my dear Panza, and tell your master that he is a most welcome visitor to my estates, and that nothing could give me greater joy than to receive him.”

Sancho, with this extremely amiable reply, returned to his master with great pleasure and recounted everything that the great lady had said, praising to the skies, in his rustic way, her great beauty, charm, and courtesy. Don Quixote arranged himself in the saddle, set his feet firmly in the stirrups, adjusted his visor, spurred on Rocinante, and with a gallant bearing went to kiss the hands of the duchess, who, sending for the duke, her husband, told him, as Don Quixote was approaching, about his message; and the two of them, because they had read the first part of this history and consequently had learned of Don Quixote’s absurd turn of mind, waited for him with great pleasure and a desire to know him, intending to follow that turn of mind and acquiesce to everything he said, and, for as long as he stayed with them, treat him like a knight errant with all the customary ceremonies found in the books of chivalry, which they had read and of which they were very fond.

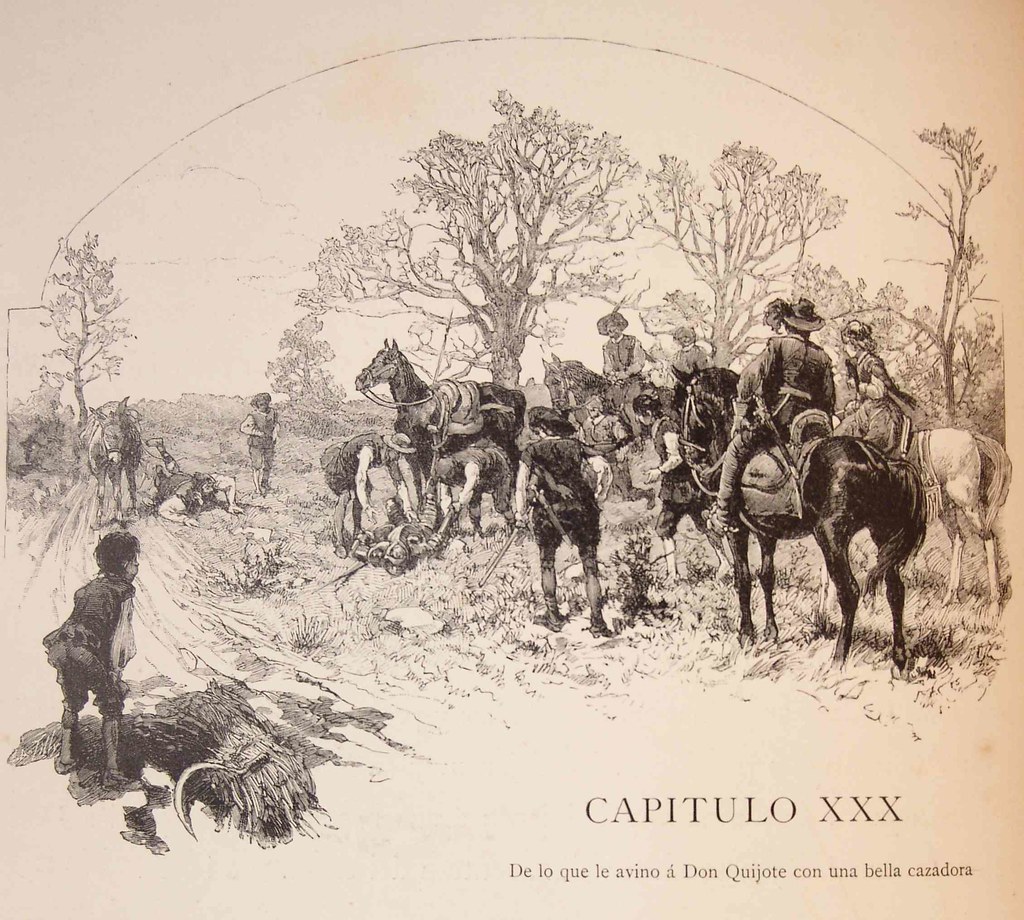

At this point Don Quixote reached them, with his visor raised, and as he gave signs of dismounting, Sancho hurried to hold the stirrup for him but was so unfortunate that when he dismounted from the donkey he caught his foot in a cord on the packsaddle and could not get free; instead, he was left dangling, with his face and chest on the ground. Don Quixote, who was not in the habit of dismounting without someone to hold the stirrup for him, and thinking that Sancho had already come to do that, went flying off Rocinante and pulled the saddle after him, for its cinches must have been loose, and he and the saddle both fell to the ground, not without great embarrassment to him and a good number of curses that he muttered between his teeth against the luckless Sancho, whose foot was still trammeled.

The duke ordered his hunters to assist the knight and the squire, and they helped up Don Quixote, who was badly bruised from his fall and, limping and hobbling, attempted to kneel before the two nobles, but the duke would not permit it; instead, after dismounting his horse, he went to embrace Don Quixote, saying:

“It grieves me, Señor Knight of the Sorrowful Face, that the first step your grace has taken on my land has turned out so badly, but the carelessness of squires is often the cause of unforeseen events that are even worse.”

“The one I experienced when I saw you, most valiant prince,” responded Don Quixote, “could not possibly be bad, even if my fall had been to the bottom of the abyss, for the glory of having seen you would lift me and raise me even from the depths. My squire, may God curse him, loosens his tongue to speak mischief better than he fastens the cinches to secure a saddle; but however I may be, fallen or upright, on foot or mounted, I shall always be in your service and in that of my lady the duchess, your most esteemed consort, and most worthy mistress of beauty, and universal princess of courtesy.”

“Softly, Señor Don Quixote of La Mancha,” said the duke, “for when Señora Doña Dulcinea of Toboso is present, no other beauty should be praised.”

By this time Sancho Panza was free of his bonds, and finding himself close by, before his master could respond he said:

“It can’t be denied but must be affirmed that my lady Dulcinea of Toboso is very beautiful, but the hare leaps up when you least expect it;445 I’ve heard that this thing they call nature is like a potter who makes clay bowls, and if he makes a beautiful bowl, he can also make two, or three, or a hundred: I say this because, by my faith, my lady the duchess is as good-looking as my mistress the lady Dulcinea of Toboso.”

Don Quixote turned to the duchess and said:

“Your highness can imagine that no knight errant in the world ever had a squire more talkative or comical than the one I have, and he will prove me truthful if your magnificence should wish to have me serve you for a few days.”

To which the duchess responded:

“That our good Sancho is comical is something I esteem greatly, because it is a sign of his cleverness; for wit and humor, Señor Don Quixote, as your grace well knows, do not reside in slow minds, and since our good Sancho is comical and witty, from this moment on I declare him a clever man.”

“And a talkative one,” added Don Quixote.

“So much the better,” said the duke, “for there are many witticisms that cannot be said in only a few words. And in order not to waste time in merely speaking them, let the great Knight of the Sorrowful Face come—”

“Of the Lions is what your highness should say,” said Sancho, “because there’s no more Sorrowful Face, or Figure: let it be of the Lions.”446

The duke continued:

“I say that Señor Knight of the Lions should come to a castle of mine that is nearby, and there he will receive the welcome that so distinguished a personage deserves, the kind that the duchess and I are accustomed to offering to all the knights errant who come there.”

By this time, Sancho had adjusted Rocinante’s saddle and carefully fastened the cinches; Don Quixote mounted, and the duke mounted his beautiful horse, and they rode with the duchess between them and set out for the castle. The duchess told Sancho to ride near her because she took infinite pleasure in hearing the clever things he said. Sancho did not have to be asked twice, and he wove his way in among the three of them and made a fourth in the conversation, to the delight of the duchess and the duke, who considered it their great good fortune to welcome to their castle such a knight errant and so erring a squire.