Introduction

«In the whole world there is no deeper, no mightier literary work. This is, so far, the last and greatest expression of human thought; this is the bitterest irony which man was capable of conceiving. And if the world were to come to an end, and people were asked there, somewhere: “Did you understand your life on Earth, and what conclusion have you drawn from it?”—man could silently hand over Don Quixote: “Such is my inference from life.— Can you condemn me for it?” I am not asserting that man would be right in stating so, but … » – Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Diary of a Writer, 1876, (ed. New York, 1919, p. 281).

«No hay en todo el mundo una obra literaria más profunda y magnífica. Esta es, hasta ahora, la última y más grande expresión del pensamiento humano; esta es la ironía más acerba que el hombre ha sido capaz de concebir. Y si el mundo llegara a su fin, y si se preguntara entonces a la gente: ‘¿Habéis entendido vuestra vida en la Tierra, y a qué conclusiones habéis llegado? El hombre podría señalar, en silencio, el Quijote’». —Fiódor Dostoievski, Diario de un escritor, 1876 (citado por la edición en inglés de The Diary of a Writer, 1876, ed. New York, 1919, p. 281).

This introduction is an explanation of why a new effort to present a translation into English of the Spanish novel Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes.

My own experience, based on conversations with some English speakers, is that very few have even tried to read it because they think it is a very hard task. And after all, why to expend time with something old and irrelevant to nowadays?

Long considered the finest work in Spanish, Don Quixote was voted by 100 writers in 2002 as the world’s best work of fiction. Authors including Salman Rushdie, John le Carré, Milan Kundera, Nadine Gordimer, Carlos Fuentes and Norman Mailer put Don Quixote way ahead of Shakespeare’s plays and epics by Dostoyevsky or Homer. This is repeated every time a similar vote is proposed.

It is not exageration at all to say that Don Quixote is the greatest book of all time. Yes, it is very tough to love this book in a translation, specially bad English translations that abound for centuries. But if the translation not only keeps the narrative of the story but the core of Cervantes magic, then I think actual readers will learn why this is really the greatest.

Don Quixote is a book in two parts, the first published in 1605, and the second part in 1615. Interestingly, Miguel de Cervantes was 58 years old in 1605, and died just one year after the second part was published. So, his masterpiece is a work from an old man, who is living his late years.

Born in 1547 in Alcala de Henares near Madrid, Cervantes enlisted as a soldier and fought against the Turks at Lepanto in 1571 where he was injured and lost use of his left hand. On the voyage home, he was attacked by Berber pirates and enslaved in Algeria for five years, and after four failed attempts to escape, was freed only after his family paid a ransom.

After returning home, he tramped the badlands of Andalusia, exacting tributes of grain, olive oil and money from hostile farmers to supply the Spanish Armada (1588) in its campaign against Queen Elizabeth’s England. And he was jailed more than once, during a lifetime of bad luck and fruitless struggles. At one point, in desperation, Cervantes applied to the court for a posting in the Indies, widely regarded as a sure-fire source of fortune and glory. He received a curt refusal, one of history’s cruellest rejection slips: «Look around for something that suits you over here.» The document is preserved in Seville’s Indies Archive, repository of a state bureaucracy that spanned the world. By the time he came to write Don Quixote, Cervantes was battered by life. However, from 1605 to 1616, Cervantes published many plays, poetry, and novels.[1]

![]()

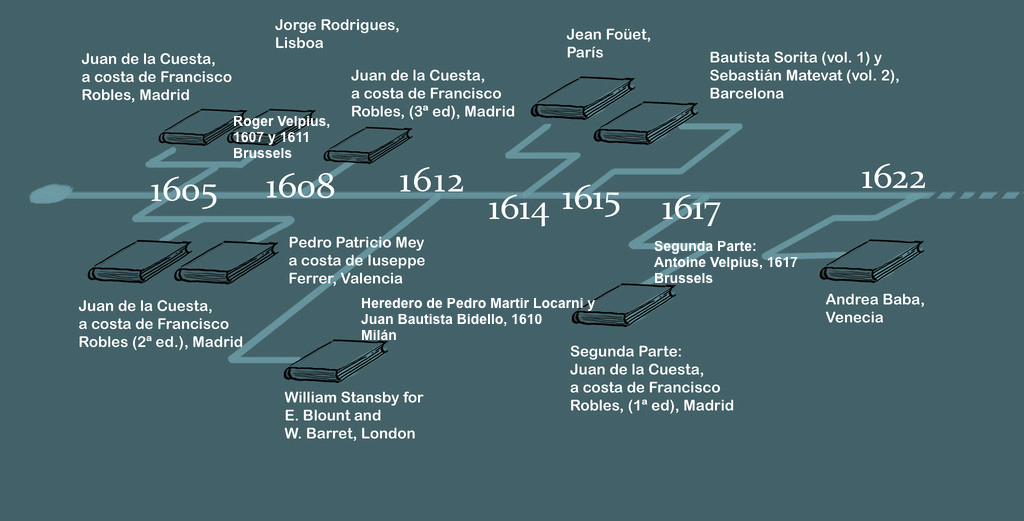

I invite readers to explore all about the very interesting story of the publication of Don Quixote. For instance, see La imprenta manual, by Jaime Moll, in Imprenta y crítica textual en el Siglo de Oro, edited by Francisco Rico. Regarding the first editions of Don Quixote, a great web page from Spanish BNE has an interactive one, and all main editions: first edition in Madrid in 1604 (signed 1605), second edition 1605 by same publisher, also printed in 1605 editions from Lisbon and Valence, editions in Brussels (1607 and 1611) and edition in Milan (1610), the third edition in Madrid (1608)… And the Second Part from 1615, with new edition in Lisbon and Brussels, and finally the printing of part I and II together for the first time in Barcelona en 1617.

Let’s start with the complete title of Don Quixote. Many essays and even entire books have been dedicated to interpret and analyze this title. In the Spanish first edition, 1605, is: ‘El INGENIOSO HIDALGO DON QVIXOTE DE LA MANCHA’ (The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of la Mancha). In Cervantes’ times the letters v and u were two versions of the same letter, and the x was pronounced much like the modern sh sound. Later, in the seventeenth century the pronunciation of the letter x shifted to something more like the way the consonant h sounds in English today. The actual letter h is silent in modern Spanish and the English h sound is best approximated by the letter j in Spanish. Therefore, Cervantes wrote QVIXOTE and pronounced it Key-sho-tay, and from here the English Quixote, the French Quichotte and Italian Quisciotte. In eighteen century the Royal Spanish Academy decided that QVI would henceforth be written QUI and all words previously written with an x would be written with a j, and so ‘QVIXOTE’ is in modern Spanish ‘QUIJOTE’ pronounced Key-ho-tay.

Furthermore, the first edition of the second part, published in 1615, says: ‘SEGUNDA PARTE DEL INGENIOSO CAVALLERO DON QVIXOTE DE LA MANCHA’ (Second Part of The Ingenious Knight Don Quixote of la Mancha).

In the second title, Don Quixote, a country nobleman (hidalgo), become a knight, that is, a knight-errant. Every reader of the first part already knew how Alonso Quijano (a member of the lesser Spanish nobility, a folkloric type, the object of deception in many plays since the end of XV century) decided to become a knight-errant and, assuming the name of Don Quixote de la Mancha, he mounted his nag, Rocinante, and headed out from his village, which name Cervantes did not care to remember, in the heart of Spain, to right wrongs and protect the oppressed. Don Quixote is a knight, but Alonso Quijano is not. So, combining hidalgo and Don Quixote in the same phrase can be the first play on words made by Cervantes or just a decision made by the editor. The way to proceed here is to explain the translator decision in a footnote.

Starting with his hero’s name, Don Quixote of la Mancha, Cervantes was making fun of the name, using a play on word: a «mancha» in Spanish is also a stain, as on one’s honor, and thus an inappropriately-named homeland for a knight. Cervantes here is playing with the word stain, translated into Spanish by mancha, and the Spanish region la Mancha. El caballero de la mancha in Spanish, can be translated as the stained knight or the knight of la Mancha, both. Translator John Ormsby, in 1885, believed that Cervantes chose it because it was the most ordinary, prosaic, anti-romantic, and therefore unlikely place from which a chivalrous, romantic hero could originate, making don Quixote seem even more absurd.

Now, let’s say a word about La Mancha, the homeland of Don Quixote. La Mancha is a natural and historical region located on an arid elevated plateau (610 m or 2000 ft.) of central Spain, south of Madrid and near Toledo. However, Cervantes’ title goes Don Quixote of la Mancha, and not La Mancha, with capital L. The name «La Mancha» is probably derived from an Arab word meaning «dry land».

![]()

In relation with the name la Mancha, it is also interesting to mention that the English Channel is known in Spanish as Canal de la Mancha. Nothing related with the Spanish region here. Canal de la Mancha is a ‘faux-amis’ translation error from French word le manche, meaning long and narrow into Spanish la Mancha. Instead of translating Canal de la Manga the translator into Spanish put Canal de la Mancha. For instance, the Catalan translation is correctly ‘Canal de la Mànega’ (Canal de la Manga).

![]()

Other interesting English word is ‘quixotic’ a word very well known by English speakers, so why not to find out the character behind it?

Three key aspects will help us to establish the context of Cervantes’ Don Quixote around 1605:

First of all, as mentioned earlier, Cervantes wrote his novel when he was almost 60 years old. In a time where life expectancy was around 50, this means Don Quixote is a book written from a life experience: Cervantes is writing at the end of his life, and even wrote the second part of his novel ten years later, just one year before his death. Moreover, his previous work, La Galatea, appeared in 1585 and the first part of Don Quixote in 1605; Cervantes published nothing in the intervening twenty years, though he had written many plays that were published after Don Quixote and not represented before being printed.

Secondly, at the time Cervantes wrote Don Quixote, at the beginning of XVII century, Spanish empire was already showing some signs of initial declining: 1588 the ‘Gran Armada’, 1596 the anglo-dutch suck of Cadiz… These national humiliations had to impact Cervantes soldier’s soul, as he had already shown it in two of the well-know Cervantes’ great sonnets: Pillip II’s tomb and the entry into Cadiz of Duke of Medina Sidonia (commander of the Armada, admiral of the ocean-sea and captain-general of Andalusia).

Thirdly, the end of the England-Spain war in 1604 was marked by England sending to Valladolid, then the capital city of Spain, in 1605, an embassy of over 500 men headed by the Lord Admiral Charles Howard, Earl of Nottingham. The coincidence of the English embassy with the 1605 publication of Cervantes’s Don Quixote was to make available with remarkable speed the most influential of Spanish texts, one that quickly made its way onto the London stage in many forms: oral report, copied manuscripts, textual fragments, unbound sheets, tentative translations. It is documented that a copy of the novel was registered in the Bodleian Library records as early as August 1605.

Don Quixote invites the reader to keep alert and active while reading, and to get humorously involved in its fiction to learn how to deceive social code of conduct which lead their lives.

How did Cervantes write? I find important to mention the kind of writer Cervantes is. It is well known that word plays abound extensively in every chapter. Let’s take an example. In a very well known adventure of Don Quixote, he descends to a cave that is very, very deep. Cervantes title for this adventure is: ‘Second part. Chapter XXII. Which recounts the great adventure of the Cave of Montesinos that lies in the heart of la Mancha, which the valiant Don Quixote of la Mancha gave happy pinnacle’. Cervantes is playing with words meaning top and down: pinnacle and cave, success and failure. This kind of jokes and word plays are in almost every paragraph of the novel. It is part of its beauty and Cervantes’ mastery as a writer.

But more important, Cervantes invents for the first time a number of literary resources: from excel dialogues to his own parody showing us a complete sample of all possible forms of narration.

Translating Don Quixote is quite difficult. John Ormsby, famous for his 1885 English translation of Don Quixote, wrote:

It is often said that we have no satisfactory translation of “Don Quixote.” To those who are familiar with the original, it savours of truism or platitude to say so, for in truth there can be no thoroughly satisfactory translation of “Don Quixote” into English or any other language. It is not that the Spanish idioms are so utterly unmanageable, or that the untranslatable words, numerous enough no doubt, are so superabundant, but rather that the sententious terseness to which the humour of the book owes its flavour is peculiar to Spanish, and can at best be only distantly imitated in any other tongue.

The number of play on words made by Cervantes throughout the book is countless, but translating the flavour of Spanish humour is the biggest task. The prospect of translating it is tremendous. However, I commend myself to Cervantes to not let me down.

Finally, some interesting articles on translating Don Quixote:

- Tilt, by Carlos Fuentes (2003) a review of Grossman’s translation of Don Quixote

- High plains drifter, by Terry Castle (2004) a review of Grossman’s translation of Don Quixote

- The Text of Don Quixote as Seen by its Modern English Translators, by Daniel Eisenberg (2008)

- Edith Grossman’s Translation of Don Quixote, by Tom Lathrop (2008)

- The challenge of translating Cervantes’s Don Quixote, by Jonathan Thacker (2016)

- Comparing Translations of Don Quixote de la Mancha compiled by Larry Lynch

- A Quixotic Endeavor: The Translator’s Role and Responsibility in Bridging Divides in the (Mis)handling of Translations by Cesar Osuna

Regarding digital editions, an excellent site is the Cervantes Project (2001-2009) housed at Texas A&M University-TAMU, a joint collaboration with professor Eduardo Urbina (project director from Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha), and Dr. Fred Jehle de Indiana-Purdue University. See Works of Miguel de Cervantes in old- and modern-Spanish spelling, based on the 18 volume edition published in 1928 by Rodolfo Schevill and Adolfo Bonilla prepared in digital form and edited by Fred F. Jehle.

I would also like to add this link to the articles of a highly respected American Hispanist, professor Daniel Eisenberg

In 2016, the US Library of Congress’ Hispanic Division presented a series of events to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the death of Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616). On December 2, the Poetry and Literature Center co-sponsored one of these events, which welcomed scholar and Johns Hopkins professor William Egginton to give a talk centered on his new book, The Man Who Invented Fiction: How Cervantes Ushered in the Modern World. Egginton’s book contextualizes and argues for Don Quixote as the first modern novel.

Madrid, 2018