1519 Timeline from 10 February (leaving Cuba to Yucatan) to 16 August (leaving Veracruz to Tenochtitlan)

10 February 1519

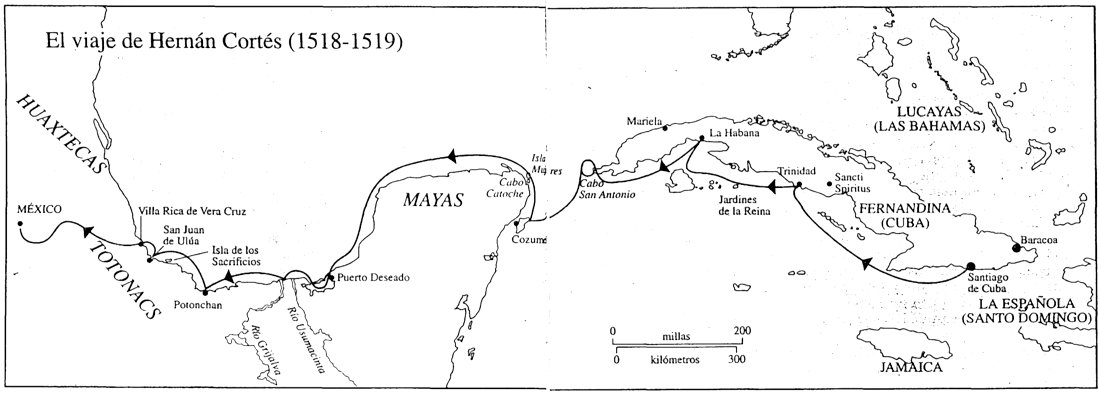

Hernan Cortes sails for Mexico with 11 ships, 508 soldiers, about 100 sailors, six cannons, and 16 horses. The expedition set out from Santiago, Cuba, on 18 November 1518. He finished fitting out at Trinidad and S. Cristobal de la Habana

Women were prohibited from embarking. However, mulatto Fabiana was an exception, and some soldiers traveled with their spouses, and five more women, who used to live amongst soldiers

Hernan Cortes was 34 years old in 1519. In the expedition to Mexico there were 300 indigenous antillean, and two blacks, Tadeo and Roberto, Juan Sedeño‘s servant. Many were massacred by acolhuas in Zultépec in 1520

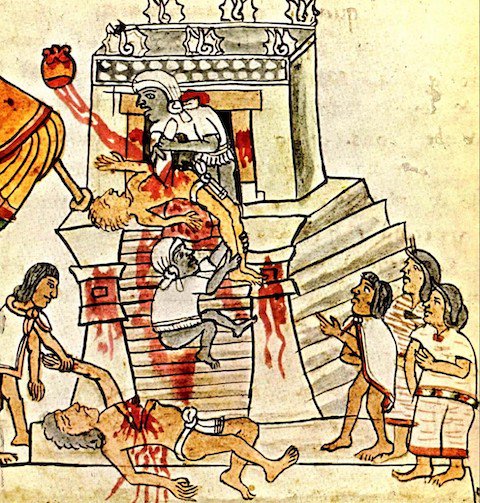

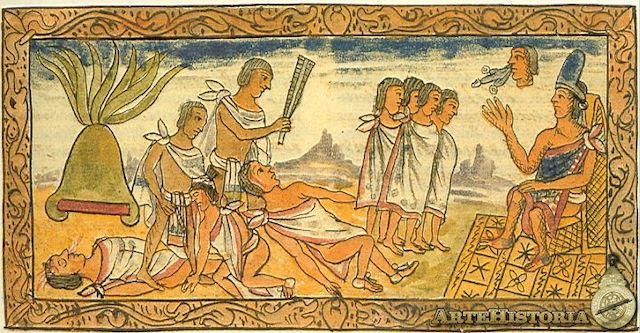

Months later, Gonzalo de Sandoval with 15 horsemen and 200 infantry arrived to Zultépec when about 550 expedition members had already been massacred in one by one sacrifices. After destruction, a new place was built: Tecoaque ‘the place where lords were devoured’

Watch video Aztec Massacre. History Documentary hosted by Jay Sanders, published by PBS broadcasted as part of PBS Secrets of the Dead series in 2016 (See program transcript)

11 captains: Alonso de Ávila, Diego de Ordás, Francisco de Morla, Francisco de Montejo, Francisco de Saucedo, Juan de Escalante, Juan Velázquez de León, Cristóbal de Olid, Pedro de Alvarado, Alonso Hernández de Portocarrero, and Gonzalo de Sandoval. And Francisco de Orozco captain of artillery and Antón de Alaminos main pilot

15 February 1519

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés was born in Avilés, Spain. He was a Spanish admiral and explorer who is remembered for planning the first regular trans-oceanic convoys and for founding St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565. This was the first successful Spanish settlement in La Florida and the most significant city in the region for nearly three centuries. St. Augustine is the oldest continuously-inhabited, European-established settlement in the continental United States. Menéndez de Avilés was also the first governor of Florida (1565–74)

17 February 1519

Hernan Cortes expedition arrived on the island of Cozumel. Earlier Spanish expeditions had talked of some Christians stranded there, so saving those Christians was one of the orders Cortes had received from Cuban governor Diego Velazquez

First ship to arrive was the San Sebastian, that had missed the starting meeting point in Cuba. Cortés arrived two days later. Upset, he imprisoned Camacho, pilot, for a short period of time and admonished Alvarado, captain, for stealing aliments and women

Having sail with big storms that dispersed the fleet, one ship did not arrived to Cozumel (Santa Cruz): it was the one with Alonso de Escobar as captain and pilot Juan Alvarez el Cojo, This ship was found some days later in Puerto Deseado, near Cabo Catoche

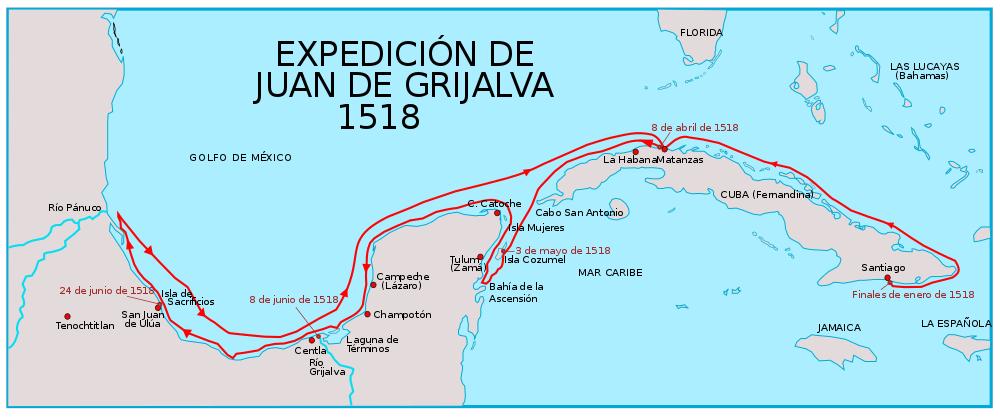

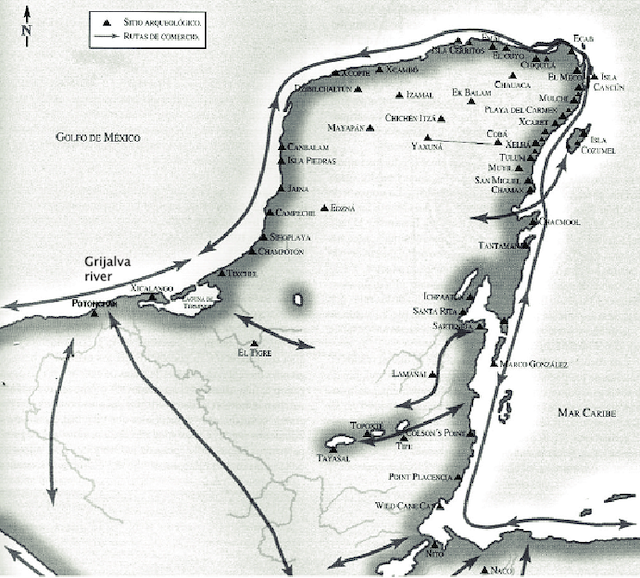

The pilots and about one third of expedition members knew Yucatan coast from previous trips, mainly the one with Grijalva in April 1518, in which the pilot was also Antón de Alaminos. Grijalva was killed by natives in Honduras on 21 January 1527

Alaminos story is also very sad: on July 26th, 1519 Cortés sent him back to Spain piloting Nuestra Señora de la Concepción with the first relation letter and presents to emperor Charles V. Arriving to Sanlúcar in October 1519. the ship was captured in Seville

Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba whom Cortés had desobeyed, had successfully manoeuvred to get the ship, Alaminos and two procurers (Francisco de Montejo and Alonso Hernández Portocarrero) captured: Portocarrero died in prison and Alaminos some time later

18 February 1519

Cozumel inhabitants had fled inland. They were Mayan subjugated by the Aztec Triple Alliance. Cortés found a temple dedicated to the goddess of rainbow, Ix Chel, in ancient Maya culture the name of the aged jaguar goddess of midwifery & medicine

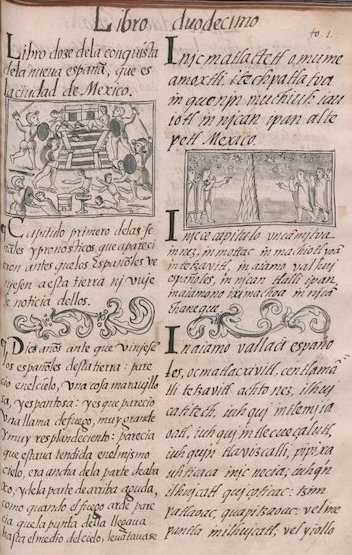

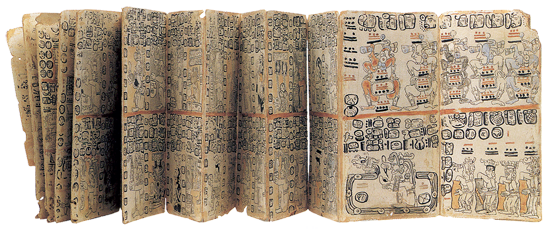

Cortés also found another surprise: tons of ‘books’. They were beautiful drawings on the inner bark of some trees (specially fig trees), smeared with bitumen and stretched to form papyrus several meters long (amatl https://bit.ly/2tqtw74 )

Cortés found a woman with her children and servants. He asked her to get people back, promising to be well treated. After that, he ordered Alvarado to give them back everything robbed from their houses. In exchange, the chief gave Spaniards fish, bread and honey

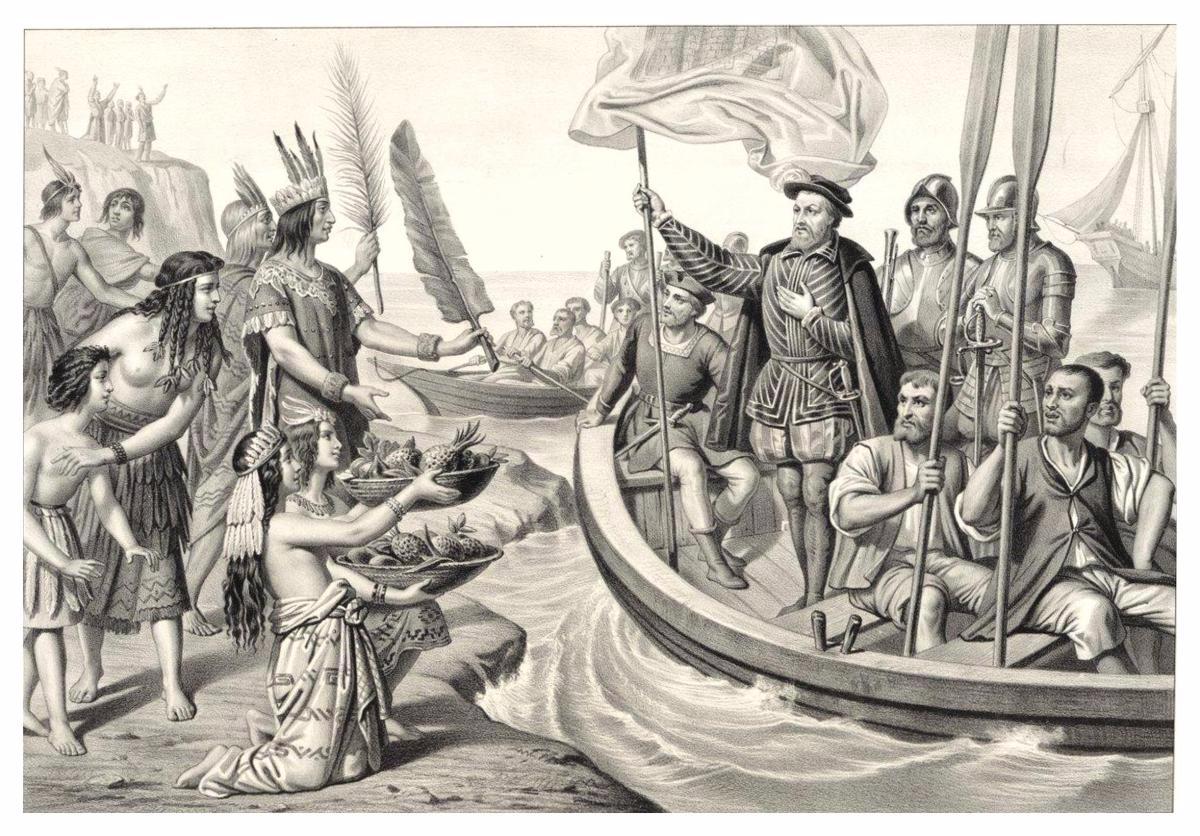

This encounter between two worlds had started and from now on everything changed for Aztecs and for Spain. Events could have continued with a withdrawal of Cortés or the founding of factories near the coast, but Spaniards were not only seeking for riches and fame

19 February 1519

For the first time, Cortés addressed locals to tell them that human sacrifices were hateful and when they asked what law to obey he told them that there was a God who created heaven and earth, the giver of all things

20 February 1519

Mayans informed Cortés that beyond the island, in Yucatan, there were two Christian captives for several years. Cortés sent 50 men in two brigantines. A man brought a message hidden in his hair with news of Cortés arrival with 550 spaniards.

“Dear Sirs and Brothers, Here, on the island of Cozumel, I received information that you are detained prisoners by a cazique. I beg of you to come here to me on the island of Cozumel. To this end I have sent out an armed ship, and ransom-money, should it be required by the Indians. I have ordered the vessel to remain stationary off the promontory of Cotoche for eight days, to wait for you. Come as speedily as possible; you may depend upon being honorably treated by me. I am here with eleven vessels armed with 500 soldiers, and intend, with the aid of the Almighty and your assistance, to proceed to a place called Tabasco, or Potonchon; etc.”

21 February 1519

Cortés is waiting for Juan de Escalante and Diego de Ordás return with Spaniards prisoners: two men living there for years would be of great help as interpreters, since Melchorejo (or Julianillo) had limited knowledge of Spanish

Melchorejo was one of the Aztec interpreters of Cortés until he was replaced by Aguilar and Malintzin. He ended up on the side of the Aztecs whom he incited to fight against the Spaniards. Later he was sacrificed to the gods, following one defeat of the Aztecs

22 February 1519

The name of prisoners were Jeronimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero. Eight years before they were shipwrecked near Yucatan, arrived to the coast with other 12 survivors, were captured by the local Maya and scheduled to be sacrificed to Maya gods

Aguilar was a Franciscan friar born in Écija, Guerrero a sailor from Palos de la Frontera both in Spain. Both managed to escape, later to be taken as slaves by another Maya chief named Xamanzana who was hostile to the first tribe. They learned the Maya language

Aguilar lived as a slave. His continued fidelity to his religious vows led him to refuse the offers of women made to him. Guerrero became a war chief for Nachan Kaan, lord of Chektumal, married a rich Maya woman and fathered the first mestizo children of Mexico

Following Bernal Diaz, when Aguilar met Guerrero to tell him about the Cortés’ offer to join him, Guerrero refused saying: ‘Brother Aguilar, I am married and have three children, and they look on me as a cacique (lord) here, and captain in time of war. My face is tattooed and my ears are pierced. What would the Spaniards say about me if they saw me like this? Go and God’s blessing be with you, for you have seen how handsome these children of mine are. Please give me some of those beads you have brought to give to them and I will tell them that my brothers have sent them from my own country’

23 February 1519

Cortés urged Mayan in Cozumel to renounce human sacrifice and replace their idols with images of the Virgin Mary. The Spanish revulsion at human sacrifice was not a justification: this attitude is typical of many Catholics in this period

(Five hundred years later)

One of the worst epidemics in human history, a sixteenth-century pestilence that devastated Mexico’s native population, may have been caused by a deadly form of salmonella from Europe, a pair of studies suggest https://go.nature.com/2NogO1W

24 February 1519

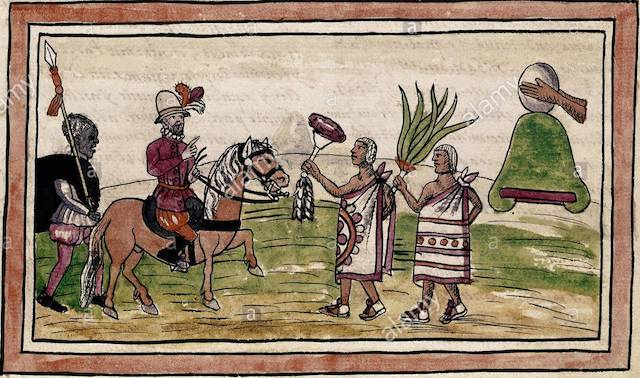

Mayans and Spaniards relations were good. Cortés spoke often about the convenience of accepting Carlos V as sovereign. The Mayans were impressed by the beards and the skin of the Spaniards, They did not show them their horses, that being secret arms, remained on the ships

25 February 1519

Cortes’ expedition had a complex legal status in Spain. Limited orders from Governor Velazquez, who had himself many restrictions to explore, as lieutenant of Diego Colon in Cuba, the son of Columbus, and the only rights’ owner to populate land

In fact, in the same days, Velazquez was expecting a royal privilege from Spain to populate, and Cortes could not do anything against royal orders if they arrived before his departure or knew about it. Cortes transformed this situation into his great opportunity

26 February 1519

Seeing that the captive Spaniards did not come, nor the Mayans who had come to look for them, it was agreed to return with the two brigantines to island of Cozumel (Santa Cruz); and arrived at the island and news was received with great sorrow

27 February 1519

Cortes said to Diego de Ordas, with great vehemence, he expected he would have fulfilled his commission better than to return without the Spaniards, and even without bringing him any information respecting them

28 February 1519

The island of Cozumel, says Bernal Diaz del Castillo, ‘was a place to which the Indians made pilgrimages (…) in great numbers to sacrifice to some abominable idols, which stood in a temple there.’

‘One morning (…) that the place where these horrible images stood was crowded with Indians (…) They burnt a species of resin, which very much resembled our incense, and as such a sight was so novel to us we paid particular attention to all that went forward’

‘Upon this an old man, who had on a wide cloak and was a priest, mounted to the very top of the temple, and began preaching something to the Indians. We were all very curious to know what the purport of this sermon was (…)’

‘(…) Cortes ordered the caziques, with the principal men among them and the priest, into his presence, giving them to understand (…) by means of our interpreter, that if they were desirous of becoming our brethren they must give up sacrificing to these idols’

‘which were no gods but evil beings, by which they were led into error and their souls sent to hell. He then presented them with the image of the Virgin Mary and a cross, which he desired them to put up instead’

‘These would prove a blessing to them at all times, make their seeds grow and preserve their souls from eternal perdition. This and many other things respecting our holy religion, Cortes explained to them in a very excellent manner’

‘The caziques and priests answered, that their forefathers had prayed to their idols before them, because they were good gods, and that they were determined to follow their example. Adding, that we should experience what power they

possessed’

‘(…) as soon as we had left them, we should certainly all of us go to the bottom of the sea. Cortes, however, took very little heed of their threats, but commanded the idols to be pulled down, and broken to pieces; which was done without any further ceremony’

‘He then ordered a quantity of lime to be collected, which is here in abundance, and with the assistance of the Indian masons a very pretty altar was constructed, on which we placed the image of the holy Virgin’

‘(…) Alonso Yañez and Alvaro Lopez made a cross of new wood (…) set up in a kind of chapel behind the altar. After all this was completed, father Juan Diaz said mass in front of the new altar, the caziques and priests looking on with the greatest attention’

1 March 1519

A soldier, called Berrio, had accused some sailors from Gibraleon (Spain) of having stolen from him a couple of sides of bacon. There were seven sailors involved in the robbery. Cortes ordered them to be severely whipped

2 March 1519

In Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Aztec Empire, messengers from the coast are reporting that strangers have arrived at Cozumel. Messengers from the coast are reporting that strangers have arrived at Cozumel. This is the third time in as many years that unusual people have visited from an unknown land. Who are they and what are they doing here?

3 March 1519

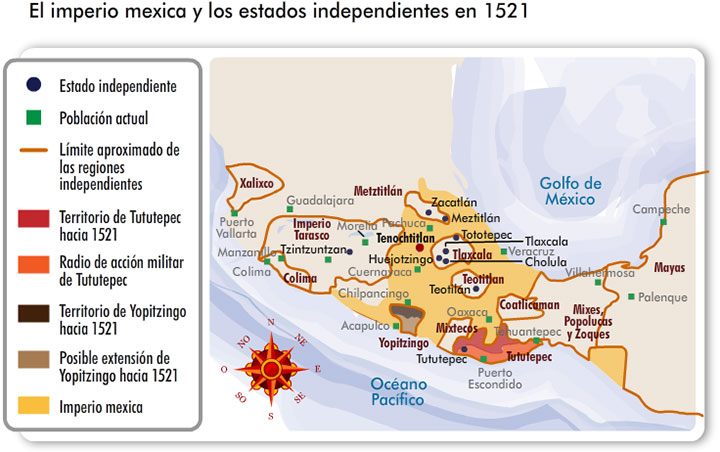

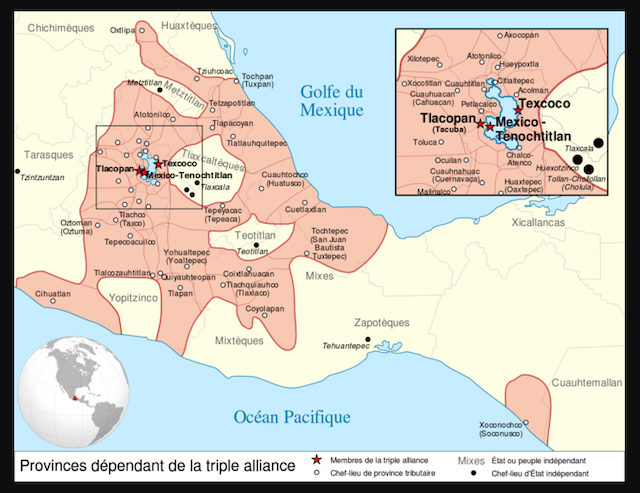

Two large powers near Tenochtitlan, the Tlaxcallan confederacy and the Tarascan empire, disputed the Triple Alliance rule, but both were being slowly encircled, and their days were numbered. The Aztecs were the greatest power in Mesoamerica

4 March 1519

Spaniard captives still missing. Cortés decides to set sails and leave Cozumel. Things start to get ready, one ship, one captain and one pilot. However, different circumstances prevent them to move forward

5 March 1519

Cortes took leave of the caziques and priests, commended them most emphatically to the image of the holy Virgin and to the cross, desiring them to pray before it, not to damage either but continually to decorate them with green boughs

He assured them that thereby they would derive great benefit. They promised to comply with all his wishes, presented him with four more fowls and two jars of honey, and then took leave of us under the most friendly embraces

6 March 1519

Cortes set sail from Cozumel and was pursuing his course with the most favorable of winds when on the very first day at ten o’clock in the morning, signals of distress were made on board one of the vessels, both by flags and the firing of guns

The ship commanded by Juan de Escalante was making straight again for the island of Cozumel. The vessel, laden with cassave-bread, was sinking fast. God forbid ! cried Cortes. Chief pilot, Alaminos, made signals for all the vessels to return to Cozumel

They unloaded the cassave-bread and found, to their great joy, that the image of the holy Virgin and cross were in the best condition, and that incense had been placed before them. It took them several days to repair the vessel

7 March 1519

When the Spaniard, who was in the power of the Indians got certain information that Cortés had again returned to the island Cozumel, he rejoiced exceedingly and thanked God with all his heart

Aguilar, the name of the captive, had unsuccessfully tried to convince Guerrero, the other captive, to join Cortés expedition. Finally only Aguilar decided to return with their comrades. Gonzalo Guerrero stayed with his new mestizo family and fighted for them

8 March 1519

Aguilar hired a canoe, with six capital rowers, for himself and the Indians who had brought him the glass beads to pay his lord for his freedom. The channel between the island and mainland, a distance of about twelve miles, was soon crossed

After they had arrived off the island and stepped on shore, some soldiers who were returning from the chase of musk swine, informed Cortes that a large canoe had just arrived from the promontory of Cotoche. Cortes despatched Andres de Tapia with a few men

As Tapia with his men approached the shore, the Indians, who had arrived with Aguilar, evinced great fear and ran back to their canoe in order to put off to sea again. Aguilar, however, told him in their language they need to have no fear

They took Aguilar also for an Indian. It was not until they had come up to them and heard the Spaniard pronounce the words God, Holy Virgin, Sevilla, in broken Spanish, and ran up to Tapia to embrace him, that they recognized this strange-looking fellow

9 March 1519

When Aguilar was introduced to Cortés, his countenance resembled that of an Indian. His complexion was naturally of a brownish cast, added to which his hair had been shorn like that of an Indian slave; he carried a paddle across his shoulder

Aguilar had one of his legs covered with an old tattered stocking; the other, which was not much better, being tied around his waist. An old ragged cloak hung over his shoulders. His prayerbook, which was very much torn, he had folded in the corner of his cloak

10 March 1519

He said, though still in broken Spanish, that his name was Jeronimo de Aguilar, and was a native of Ecija (Spain). About 8 years ago he had been shipwrecked with 15 men and 2 women, on a voyage between Darien (Panama) and the island of St. Domingo

They had undertaken that trip on account of a lawsuit between a certain Enciso and a certain Valdivia. They had 10,000 pesos on board, and papers relating to the lawsuit. The ship struck against a rock, and they had not been able to get her off again

The whole of the crew then got into the boat, in the hopes of making the island of Cuba or Jamaica, but were driven on shore by the strong currents, where the Mayan had taken them prisoners and distributed them among themselves

The most of his unfortunate companions had been sacrificed to their gods, and some had died of grief, of which also both the women pined away; being soon worn out by the hard labour of grinding, to which they had been forced by the Indians

Aguilar himself had also been doomed as a sacrifice to their idols, but made his escape during the night, and fled to the cazique with whom he had last been staying

Of all his companions, he and Gonzalo Guerrero, were only living. Aguilar had tried his best to induce him to leave, but in vain. Speaking both Maya and Spanish, Aguilar was a key value for Cortés

11 March 1519

The caziques of Cozumel showed Aguilar every possible friendship when they heard him speak in their Maya language. Aguilar advised them always to do honour to the image of the holy Virgin and cross, as they would prove a blessing to them

Aguilar was the first to send a shipment of cocoa to Europe with his recipe. The Mayas took it smoothie and mixed it with chili. He sent several bags to Antonio de Álvaro, abbot of the Monastery of Piedra in Zaragoza, where a chocolate was first made around 1534 (ver http://www.mexicolore.co.uk/maya/chocolate/cacao-use-among-the-prehispanic-maya)

Although Guerrero’s later fate is uncertain, it appears that for some years he continued to fight alongside the Maya forces against Spaniards, providing military counsel and encouraging resistance; it is speculated that he may have been killed in a later battle

12 March 1519

Cortés is eager to set sails and continue his journey to mainland, meet the Aztec civilization of which they speak since his arrival in Cozumel, and gain fame, glory, and fortune

Cortes is finishing his plans, based on his knowledge of the Spanish laws (Siete Partidas), and his extraordinary skill in exploiting it to justify and legalize his own very difficult position after breaking with the governor of Cuba, and setting out unauthorized

13 March 1519

The caziques of Cozumel, upon Aguilar advice, begged of Cortes to give them letters of recommendation to other Spaniards who might run into their harbor, in order that they might not be molested. Cortés readily complied with this request

14 March 1519

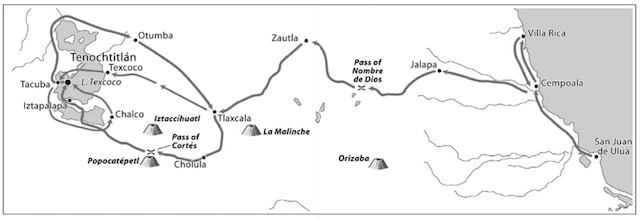

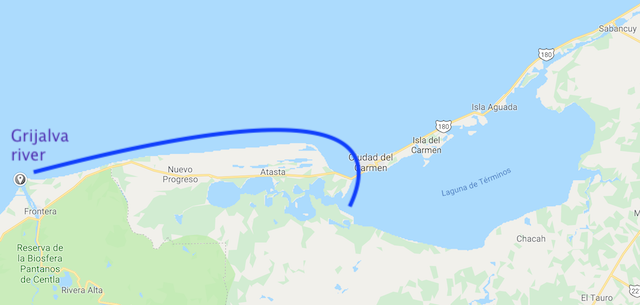

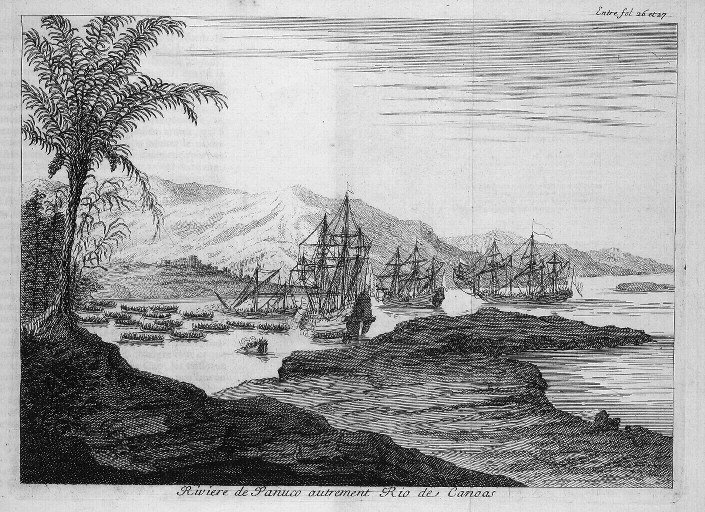

After mutual signs of friendship with the caziques of Cozumel, Cortés finally weighed anchor, and set sail for the river Grijalva, formerly known as Tabasco River, well known for pilots like Alaminos. Juan de Grijalva named this river in 1518

In 1518 Hernan Cortes stayed at Grijalva’s home in Trinidad, Cuba, at the start of his Mexican expedition. He recruited men there, including the five Alvarado brothers. Grijalva was killed by natives in Honduras on 21 January 1527

15 March 1519

Wind blowing violently last evening, towards midnight the wind abate and when daylight broke forth, all vessels again joined each other; Velazquez de Leon’s one was missing, which occasioned great anxiety, for they concluded she had been shipwrecked

Cortes told principal pilot Alaminos not to continue without gaining some certain knowledge as to her fate: signals were made for all the vessels to drop anchor, to give the missing ship time to join the fleet

Alaminos said to Cortes: You may be sure, sir, that she has run into some harbour or inlet along this coast, where she is now wind-bound; for her pilot Manquillo has twice before visited these seas, with H. de Cordoba and Grijalva, and is acquainted with this bay

Upon this, it was resolved that the whole squadron should return to the bay which Alaminos was speaking of, in search of the vessel: to their great joy they indeed found her riding there at anchor, and they all remained there for one day

16 March 1519

Alaminos went on shore in two boats. They saw several regular corn plantations and four cues or sanctuaries on high, with numerous figures, mostly in the shape of women of considerable height; whence this promontory was called Punta de las Mujeres

17 March 1519

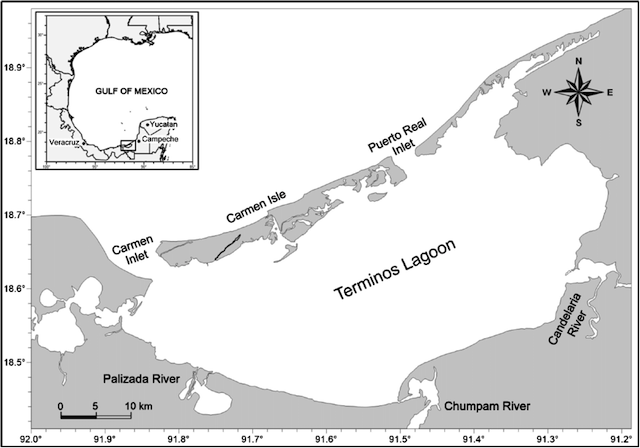

Cortés sent a captain Escobar with a fast-sailing vessel of small tonnage to explore the coast. Escobar arrived to Términos Bay (laguna de Términos, Campeche), where he found a lost greyhound in the previous trip of Grijalva

The greyhound was quite glossy and fat, and immediately knew the ship again as it entered the bay, wagging its tail, and jumping on board. Escobar intended to wait until the rest of the fleet should come up, but was driven way out to sea by a strong south wind

18 March 1519

Cortés arrived at the entrance of Términos Bay, and finally seeing Escobar, who was obliged to hold out to sea. They arrived in the waters off Potonchan, and Cortes ordered Alaminos to run into the inlet where Cordoba and Grijalva fought years ago

Cortes’s intention was to punish the inhabitants severely, and many soldiers who had participated in those fights begged of him to take revenge. But Alaminos said they should lose more than 3 days by running in, and if the weather became unfavorable, above eight

The wind was most favorable to reach the Tabasco river, which was their chief object. Accordingly they put out to sea, and reached the Tabasco river after three days’ sail

19 March 1519

Cortés plied Aguilar for information trying to determine the best approach to deal with the mainland Mayas, who had successfully repelled Córdoba in 1517 at Champoton, killing 20 of his force. Córdoba was also wounded and died in Cuba shortly after

20 March 1519

Hernán Cortés strode to the bow of his flagship Santa María de la Concepción, a one-hundred-ton vessel and the largest of his armada, and scanned the horizon, ready to land near Grijalva river (Tabasco river)

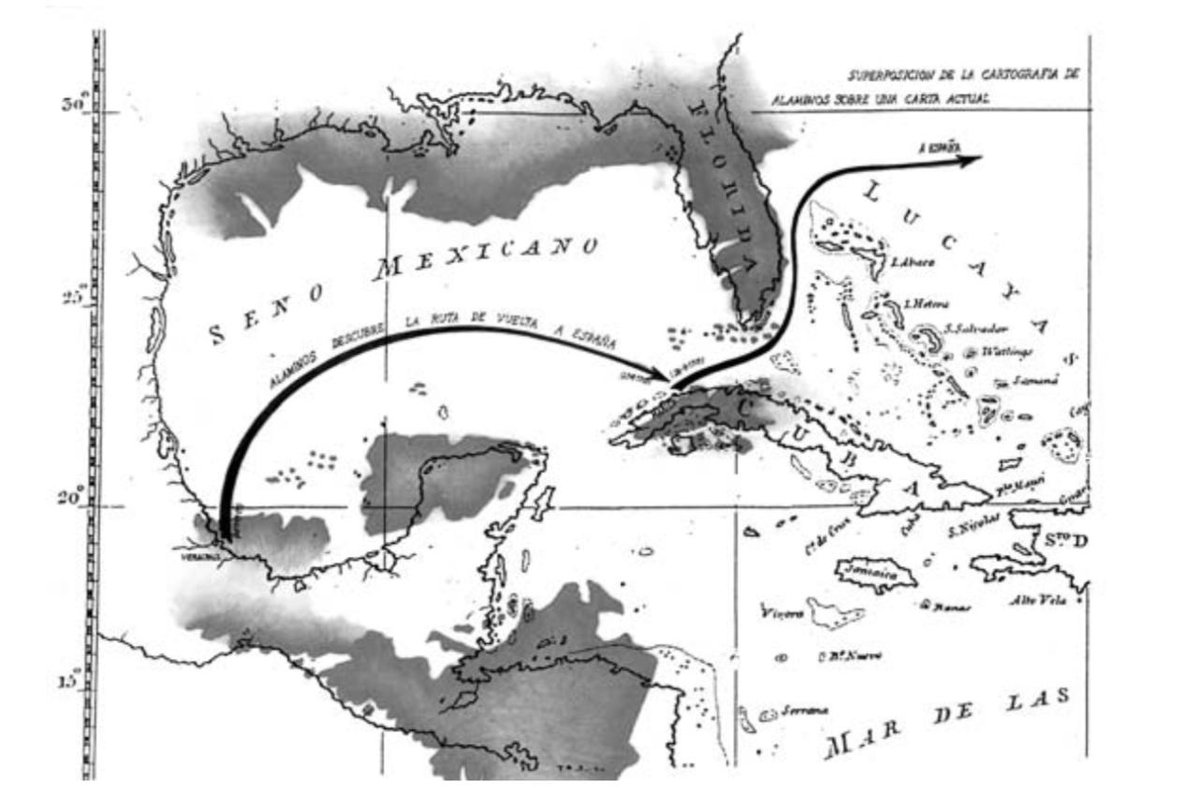

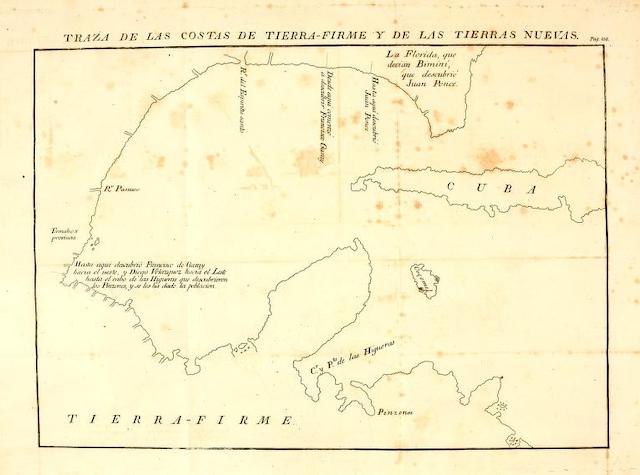

Meanwhile, around this date, Álvarez de Pineda in the name of Francisco de Garay, governor of Jamaica, with four ships, carrying 270 men, sailed from Jamaica to explore the Gulf coast

They aim to explore the coast between the discoveries of Ponce de León on the Florida peninsula and those made on behalf of Diego Velázquez along the southern Gulf, in hope of finding a strait to the Pacific Ocean

After clearing the Yucatán Channel, which separates Cuba and the mainland, the ships continued north until the Florida panhandle was sighted, then turned east, expecting to find the passage that was supposed to separate the “island of Florida” from the mainland

Álvarez de Pineda thus proved that Florida was not an island as it was reported in 1513. Contrary wind and strong current forced them to turn about, then sailed west and south along the coast until they found Cortés’s nascent settlement of Villa Rica, August 1519

When Alonso Álvarez de Pineda explored the Gulf Coast from peninsular Florida to Veracruz in 1519, the territory was named Amichel

21 March 1519

The armada moved together under full sail before favorable winds towards the Tabaco river entrance (renamed by the Spaniards the Rio de Grijalva) well know by Alaminos and other expeditionaries from previous trips

22 March 1519

The fleet anchored near a sandbar at the wide and tranquil mouth of the Grijalva river, near the native settlement of Potonchan

Because the water was too shallow for the bigger ships, Cortés assembled a force of two hundred soldiers and headed into the mouth of the river in brigantines and smaller vessels, the oar boats towed by the caravels

The boats slipped slowly upriver and into dank and briny mangrove swamps; the thick canopy overhead screamed and keened with shrill bird cries. The men found the place putrid-smelling

Cortés warned his pilot when he spied dugout canoes paddling toward them from upriver. Along the banks of the river, interspersed among the trees, stood hordes of Tabascan warriors armed with bows and spears, their bodies painted ochre and red, plumed in feathers

Cortés directed the bulk of his boats to a headland a safe distance away and had cannons and falconets unloaded while crossbowmen and harquebusiers stood ready. He hoped not to have to fight, but he would be ready, and his men remained at attention at all times

With Aguilar at his side, Cortés moved upriver and neared Pontonchan, a thriving commercial center, and met the first Tabascan warriors in their dugouts. Through Aguilar, he called out that he came in peace and wished only to trade goods for food and obtain water

(He had plenty of both—he was in fact nosing around for gold.) The Tabascans responded violently, shouting back at Cortés that the Spaniards should not attempt to land. The Tabascans warned that all would be killed if they advanced beyond a line of palm trees

The Spaniards named Punta de los Palmares (Point of Palm Trees).

Cortés pondered his next move as he scanned the scene, estimating the town to possess some twenty-five thousand inhabitants. The Spaniards were dramatically outnumbered

Cortés continued to negotiate, reiterating his desire for food and underscoring that he was perfectly happy to pay a fair price for whatever they might provide. As darkness fell, both sides stood at an impasse

The Tabascans said that they would report to their chiefs in town and determine whether they wished to trade. They told the Spaniards to meet them in the town square in the morning

That night, sleepless on the sandy beach and anticipating battle, Cortés sent a force of one hundred men to the outskirts of the village with orders to support him in a surprise attack from the flanks if a skirmish ensued

While the rest of the Spaniards lay swatting bugs and sweating in their heavy armor, the Tabascans evacuated the town of all women and children and hid them deep in the river delta forests

To thwart the Spaniards’ approach, Tabascan builders erected barricades and obstructions from tree trunks and branches around the town and along the river

23 March 1519

In the morning, the Tabascan representatives reiterated that they were unwilling to trade. Cortés and his men boarded their shallow-draft warships and proceeded upriver toward the town. A throng of war-painted Tabascans lined the river, chanting, shrieking, beating drums, and blowing weird siren-songs through conch shells.

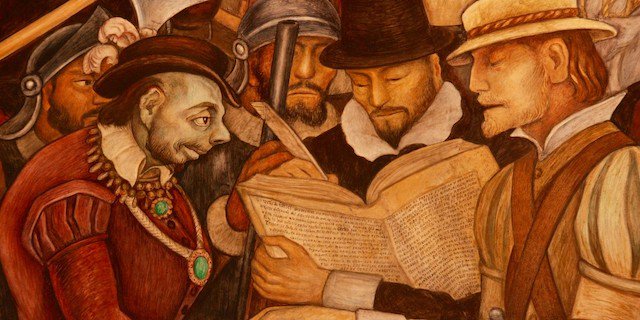

Standing at the prow of his boat with Aguilar interpreting and Diego de Godoy, the king’s notary, as witness, Cortés addressed the Tabascan chiefs with Spain’s legally required forewarning or requerimiento. This ironic, devious, and self-justifying speech called on the Indians to accept Christ in lieu of their own gods and the Spanish king as their sovereign. They must acquiesce to become vassals of Spain and agree to Christian preaching and education, for which they would receive untold rewards, including peace, prosperity, and everlasting life.

The Tabascan response to this slick Spanish diplomacy was a rain of arrows, spears, and stones, and the first battle of Cortés’s conquest was joined. Though he was a leader of men, until this moment in his career Cortés had never commanded men in battle.

Cortés was forced to think quickly. The Tabascans followed their onslaught with a full charge into the river, rushing to attack the boats and pouring forth in their own dugout canoes. Some Spanish soldiers disembarked and they fought hand to hand with the Tabascans in waist-deep water, war clubs and spears meeting for the first time the fire-hardened Toledo steel of Spanish swords. With great difficulty and severely outnumbered, Cortés and his men managed to slash their way to land, but the riverbanks were so mucky that Cortés lost a boot as he clambered ashore, one foot bare. The boot was retrieved. He then commanded from the densely foliaged bank. All the while men fought, and the Tabascan warriors cried out in their language to immediately “kill or capture the Captain.”

Surrounded, the Spaniards fell into tight ranks and fought as they had been trained, in well-organized and highly regimented squads, while their enemies came at them en masse in a series of surging and retreating waves. Their organization paid off, and soon the Spaniards were tearing down and breaking through the newly constructed timber barricades and pushing the Tabascans back, the harquebusiers firing deadly balls at close range.

Just then, having heard the battle joined, Alonso de Ávila and his men, whom Cortés had ordered hidden the night before, made it through the palm woods and marshes in time to support, and now the Tabascans felt two-front pressure, as well as the deafening and utterly foreign explosions of cannons and falconets. They fled, retreating beyond the town to dense mangrove swamps and jungle, even still firing arrows and hand-thrown darts. The Spaniards’ surprise tactic had worked perfectly, and as the last of the Tabascan warriors disappeared into the shadows, Cortés and his men convened in the village square, swords still brandished.

With his royal notary Godoy at his side, Cortés strode to a great ceiba tree that stood in the central square. Raising his sword, he slashed the massive trunk symbolically three times, exclaiming before his men that he now conquered and took possession of this land “in His Majesty’s name!” (This act would have had a profound effect on the native population, for the ceiba tree was sacred, believed to be the pillar holding up the heavens themselves.)

Bernal Díaz, nursing an arrow wound in his thigh, recalled that he and a group of soldiers deeply loyal to Cortés replied with vigorous shouts of “Hear, hear,” supporting Cortés’s taking possession in the name of “His Majesty the King.” Díaz added that he would “aid against any challengers.” But a small group of soldiers, followers of Diego Velázquez who were still loyal to him, grumbled that Cortés had conveniently forgotten to mention Velázquez, under whose sponsorship they were supposedly operating. In a brazen move that did not go unnoticed by the Velázquez camp, Cortés disregarded them, for the first time publicly ignoring his patron. His actions had placed him directly under the auspices of the king, and no one else. It was his first formal move to distance himself from Velázquez.

Cortés ordered his men to rest and made an assay of his forces, determining that though a few were wounded, no Spaniard had been lost. They slept that night in the temple square, numerous sentinels posted on the perimeter, and awoke the next morning to some ominous news.

This battle is known as the Battle of Potonchan, March 23, 1519

24 March 1519

Cortés gets news that during yesterday’s battle Melchior had fled, joining the Tabascans. He was a Maya taken prisoner two years ago during an earlier expedition, having been taught some Spanish by his captors, and converted into an interpreter

Cortés feared that Melchior might inform the Tabascans of the Spaniards’ numbers and details of their weaponry, but he could do nothing but scowl in disgust at the interpreter’s treason

Cortés sent two captains, Pedro de Alvarado and Francisco de Lugo, each with about a hundred men (including specialists, musketeers and crossbowmen), to scout the nearby countryside in search of provisions

They advanced in different directions into the interior. After only three miles Lugo met great companies of archers, and others with lances and shields, drums and standards, who immediately attacked them, surrounding Lago’s men on all sides

The situation grim, Lugo dispatched a brave Cuban runner to appeal to Cortés for reinforcement. In the meantime, Lugo organized his small force in tight ranks and had his crossbowmen, falconets, and harquebusiers fire volleys at the swarming Tabascans

Hearing Lugo’s musket fire, and the enemy’s war-whoops and the beating of drums, Alvarado and his company sped to the battlefield. They arrived just in time to support Lugo. The two divisions defended themselves and repelled the onslaught as they backed into camp

They captured three prisoners, from whom Cortés got some shocking news: all the able-bodied Tabascan warriors from the vicinity would converge at the town of Cintla the next morning to make war on the intruding Spaniards

Most disconcerting of all, prisoners claimed that these warriors numbered over 25,000, about fifty times Cortés’s fighting force. They intended to surround the Spaniards and kill every last one of them

Then, in a move that would become one of his diplomatic trademarks, Cortés released a prisoner with gifts of green beads with the message to his chiefs that he wished only to trade and that he came in peace. Once they were gone, he immediately prepared for war

Cortés ordered wounded men back to the ships; crossbowmen, harquebusiers, lancers, swordsmen, and light gunners, prepared for action. He called for more artillery, dry powder, and six of the heavy cannons to be removed from the ships and transported ashore

Then, sensing that the time was right, Cortés called upon his secret weapon: the entire cavalry of sixteen Spanish horses. The animals, stiff and sore from their long journey, were lowered by pulleys and led ashore

They were the first horses to set their hooves on the Mexican mainland since before the Ice Age, when the native animals became extinct in the northern hemisphere

As the sun went down, the horses were exercised and fed. The cavalrymen prepared for battle, donning heavy steel body armor, breast and back plates, plus metal tassets for their thighs and rerebraces and vambraces for their arms

These they would sleep in, sweating through the humid night. The horses were fitted with breastplates of their own, and small bells that jingled as they went, serving to further frighten the enemy and to alert the Spaniards to the cavalry’s location

25 March 1519

The day of annunciation to the holy Virgin, at daybreak Cortés attended the Mass of Fray Bartolomé de Olmedo, the expedition’s chaplain, then he led his force of five hundred men out of the village and onto the plain of Centla

Diego de Ordás was the captain of the infantry, artillery Mesa, and Cortés himself was commanding the cavalry of 14 horsemen. Some ten thousand Tabascan warriors poured into the open maize fields, and other ten thousand were behind in support

Some warriors were decorated in ornate feather crests, pounding drums and blowing trumpets to instill fear as they ran. Their screaming faces were streaked with white and black paints signifying rank, and they carried long bows and arrows, shields and spears

The Spanish infantry, foot soldiers and musketeers and crossbowmen, took the initial onslaught, and some seventy Spaniards were badly wounded in close hand-to-hand combat. One named Saldaña was struck by an arrow in the ear and instantly dropt down dead

Cortés and the cavalry had been separated from the infantry by swamps and marshes and deep irrigation ditches that the horses could not cross, and so they were slow to arrive in support of the infantry

The infantry battled wave after wave of brave warriors using skillful sword work to repel continuous and numerically superior assaults. They fired their matchlocks, falconets and cannons. As the smoke and dust cleared Cortés arrived from the rear with his cavalry

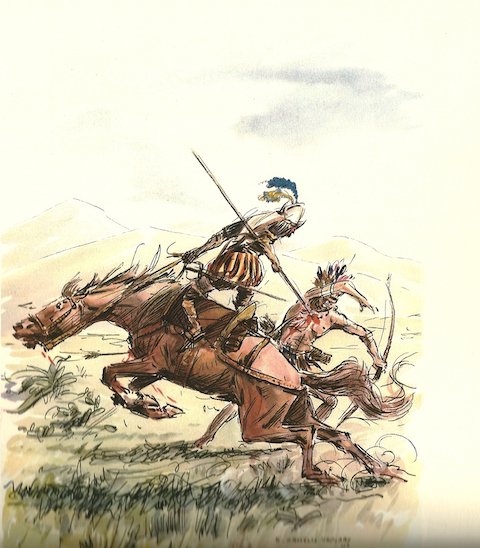

Cortés and his cavalry charged the field, the riders wielding spears in the first mounted combat in the New World. Horse and rider galloped into the fray at great speed, charging the crowd and impaling the warriors from elevated positions

Cortés and his men speared at will, then rode and wheeled and came again, skewering and trampling the confused Tabascans. Then they would retreat to the periphery, while cannon and gunfire boomed through the valley

The Indian warriors, having never before witnessed either horses or firearms, looked on in dismay as their compatriots were easily run down. They fought bravely but were no match for the killing efficiency of firearms or horses and expert riders

Tabascans fled in terror. Within a few hours smoke hung low in the Centla Valley, and more than eight hundred warriors lay dead in the fields. Cortés’ first major military engagement on mainland Mexico had been a rout

Cortés and his cavalrymen dismounted, unsaddled, and tethered their horses, treating some that were wounded. He ordered rest and medical attention for his wounded men, nearly a fifth of his fighting force, though many of the wounds were minor

That night more than a hundred additional Spaniards fell ill with fevers, cramps, and general malaise, likely from foul water drunk from the streams, coupled with the oppressive heat and humidity

Miraculously, only two of Cortés’s men died on the battle of Centla, one slashed through the throat, the other succumbing to an arrow in his ear. It was March 25, 1519, and the conquest of the Americas had begun in earnest

26 March 1519

Willing to start peace talks, Cortés sent 5 prisoners to communicate to their caziques telling them how Spaniards longed to become their friends. First, Tabascans sent some slaves with fowls, baked fish and corn-bread. Cortés asked for their lords

Cortés treated these peculiar emissaries very kindly, presenting them with blue beads in token of peace, and in order to gain their good wishes. Aguilar told them that If their lords were desirous of making peace, persons of rank should be sent, not slaves

27 March 1519

Tabascans sent above thirty of their principals, well dressed, bringing with them, fowls, fruits, and corn-bread, and begged permission of Cortes to burn and bury the bodies of their fallen countrymen

This being granted, they brought along with them a great number of people

to burn the bodies, and bury them according to their custom. Cortes himself went to watch their proceedings, when they assured him they had lost above 800 killed, no counting the wounded

They added that at present they did not dare to enter into any treaty, as the following day all the chiefs and principal personages of the district would assemble to take Cortés’s offers of peace into consideration

28 March 1519

Cortés noticed that the natives seemed terrified of the horses and cannons. Realizing that these men understood neither the horses nor the fire-bursting cannons and guns, he prepared a show

Cortés: “It appears to me, gentlemen, that the Indians stand in great awe of our horses, and imagine that these and our guns alone fight the battle. A thought has just struck me which will further confirm them in this notion…

… You must bring here the mare of Juan Sedeno which foaled on board a short time ago, and fasten her here where I am now standing. Then bring also the stallion of the musician Ortiz, which is a very fiery animal, and will quickly scent the mare…

… As soon as you find this to be the case, lead both the horses to separate places, that the caziques may neither see the horses, nor hear them neigh, until I shall be in conversation with them.”

A little after midday, forty caziques arrived in great state and richly clothed, bringing food and offerings, including various turquoise objects and, more important, intricate masks, sculptures, and diadems fashioned in gold

They saluted Cortes, begged forgiveness for what had happened, and promised to be friendly for the future. Cortés said he was vassal of the mighty king and lord the emperor Carlos, who had sent him to favour and assist those who should submit to his imperial sway

If not, the cannons would be fired off. Cortes, at this moment, ordered that a cannon be fired at dangerously close range. The thunderous report reverberated, and the hiss of the ball whistled past the Indians’ heads and exploded foliage a great distance away

The caziques who had never seen this before, appeared dismayed, and believed everything that Cortés had said, who, nevertheless, through Aguilar, the interpreter, wished to console them and assure them that he had given orders that they should not be harmed

At this time, the stallion was carried and tied a short distance from the place where Cortés and the caziques were celebrating the conference. The stallion caught the scent of the mare and reared, kicked and neighed, then pawed and stomped the ground

When Cortes found what effect this scene had made upon the Indians, he rose from his seat and walking to the horse took hold of the bridle, whispered something and calmed it down. Cortés said that, if they cooperated, they would not be harmed

While all this was going on, above thirty porters arrived with fowls, baked fish, and fruits. A lively discourse was now kept up between Cortes and the caziques, who in the end left him with the assurance that the following day they would return with a present

29 March 1519

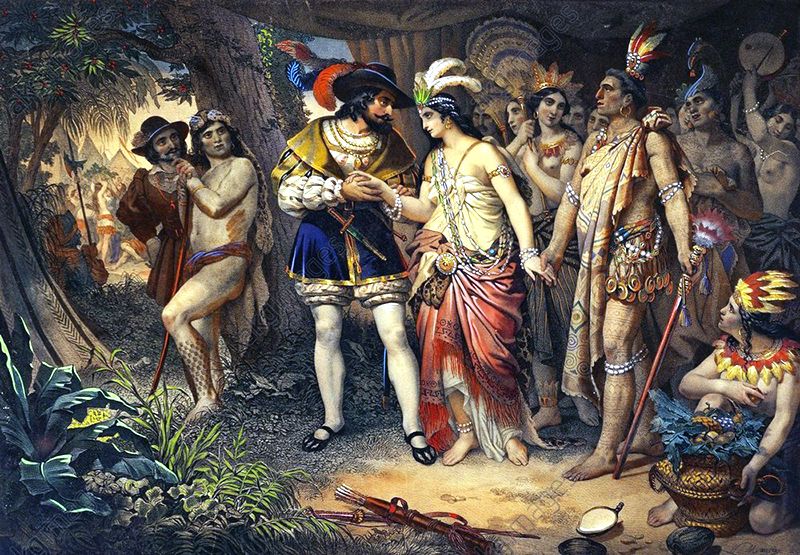

A number of Maya caziques arrived with more gifts, more gold, small figurines of dogs, ducks, and lizards, and twenty young slave women, who they said could be used for various tasks, although it was easy for them to become concubines as well

Pleased, Cortés inquired about the gold. Did they have more, and if not, where might he find more? Where were the mines? The Tabascans assured Cortés that they had no more gold, but they pointed to the northwest and said, “Culua, Mexico, Mexico.”

Before accepting the women, Cortés ordered that they be baptized the next morning to comply with the Castilian law that allowed to maintain relations of concubinage only between Christian and single people

Among these slaves one was a very fine woman, Malinalli, who became key for Cortés and the conquest of Tenochtitlan. She was born around 1500, possibly near Coatzacoalcos, former Olmec capital located at the southeast of the Aztec Empire, in what is now Veracruz

She belonged to a principal family: his father was the ruler of the city of Painala. But after her father died and her mother remarried a local man, the couple decided to get rid of the little Malinalli to secure their own heir

Taking advantage of the fact that a girl of the same age had died in the village, they made her look like her daughter and, sheltered in the darkness of the night, they gave Malinalli to some merchants

They sold her as a slave in the market of Xicalanco to other Maya merchants, who in turn ended up selling it to the lord of Potonchán, named Tabscoob. It was he who would finally deliver it to Cortés. Tabscoob also had led the Chontal Maya in the Battle of Centla

Malinalli Tenépatl spoke Nahuatl, that was a lingua franca for trade and rule during the apogee of the Aztec empire. With the lord of Potonchán, she learned to speak Mayan too. Then, she could converse with the Spaniards through Aguilar, who spoke Mayan

30 March 1519

A cross and altar were erected, and the figure of the holy Virgin being placed thereon. Father Bartolome de Olmedo read mass and, with the assistance of Aguilar, said to the twenty slave women:

“You all should abandon your belief in idols, and no longer bring them sacrifices, for they were not gods but evil spirits; you have up to this moment lived in gross error, and should now adore Jesus Christ”

After this address, the women were baptized, and Malinalli was named Marina. Being a lady of distinction, she was known as Doña Marina. Natives called her Malintzin, with -tzin as an honorific suffix. From here, in Spanish she was also know as Malinche

These were the first who were baptized in New Spain, and were distributed among Cortes’s chief officers. Doña Marina, who was the prettiest, the most active and lively of the group, was given to Puertocarrero, a stout cavalier and cousin to the earl of Medellin

Later, in July 1519, Cortés sent Puertocarrero to Spain, took Marina unto himself, and years later had a son by her: Martín Cortés, who was the firstborn male of Cortés. Born in 1523-4, he was recognized by his father and legitimized by Pope Clemente VII in 1528

Martín Cortés, the mestizo, was soon separated from his mother and given to a cousin of his father, Juan de Altamirano. Martín traveled with his father to Spain in 1529 and was pageboy of Felipe II of Spain (born in 1527) when this one was still prince

As for Malinalli, she died early, around 1530, after acting decisively as an interpreter, adviser, lover and intermediary of Cortés. Its reputation has changed over the years according to the perspectives of the time, especially after the Mexican Revolution

Cortés remained in this place until around Palm Sunday of 1519, April 17, some three weeks in total

31 March 1519

Cortes spent five days in this place, partly to heal the wounds of his men, partly for the sake of those who suffered pain in the groin, but who soon recovered. Cortés used these days in useful conversations with the caziques

He talked to them about the emperor, of his numerous lordly vassals, and the advantage they would gain by having subjected themselves to him; as, for the future, in all their difficulties they would only have to apply to him, and he would come to their assistance

The caziques thanked Cortés for this offer. They solemnly declared themselves to be vassals of the great emperor Carlos, and these were the first among the inhabitants of New Spain who subjected themselves to his majesty

Cortés remained in this place until around Palm Sunday of 1519, April 17, some three weeks in total

1 April 1519

The first Spanish city in Mexican territory was in all solemnity named Santa Maria de la Victoria. It was located in what is now the state of Tabasco, in Mexico. Now disappeared (see map of 1549)

It was in the place that occupied the Maya city of Potonchán, capital of Tabscoob, on the left bank of the river Grijalva (in front of the present port of Frontera) a few leagues from the mouth to the sea. It is believed that the city of Frontera is the same town

Once capital of Tabasco, it did not have a great development due to the inhospitable of this territory covered with jungles, water and large marshes. in 1528 Francisco de Montejo started the conquest of Yucatan from there (conquest finished in 1542)

In 1641, viceroy Diego López Pacheco moved administration from Santa María de la Victoria to San Juan Bautista (today Villahermosa) and the villa was definitively abandoned

2 April 1519

The caziques, being questioned as to where they got their gold and the trinkets, answered from the country towards the setting of the sun, and pronounced the words Culua and Mexico. At that time Cortés did not comprehend the meaning of these words

They told Cortes, partly by signs, that Culua lay at a great distance, at the same time continually mentioning the word Mexico, Mexico. Cortés was then still ignorant what they wished to convey to him

3 April 1519

The caziques explained to Cortés that the war was at the instigation of their brother, the cazique of Champoton, who had previously accused them of cowardice for not having attacked Grijalva expedition last year

The same advice was also given them by Melchior, the interpreter who had run away in the battle, telling them not to leave invaders any peace day or night, as they were but few in number. Cortés desired that he should be delivered up to him

But they declared they did not know what had become of him, as on the unfortunate termination of the battle he had immediately fled. This however was an untruth, as he had paid for his advice: as shortly after the battle he was seized and sacrificed to their gods

4 April 1519

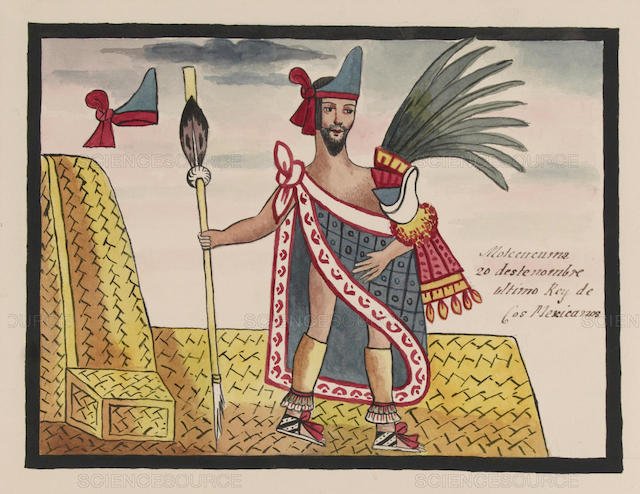

In Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztecs, rumours of the arrival of a powerful group of people had been confirmed by emissaries. When Moctezuma heard of Cortés’s arrival, he refused to meet with the Spaniards, instead sending gifts,

offering the tribute that frequently resolved disputes in Mesoamerican society. The Aztecs’ “superstitious” belief that Cortés was a god is a myth: they knew that other conquerors had been killed the year before, some offered to their gods as sacrificial victims

5 April 1519

When the Spaniards arrived, women were given to them as peace offerings along with food and supplies. The women had the agency to adapt to their new conditions, and some started to learn Spanish and to teach the Spaniards their own language

Malintzin had to adjust to the Spanish form of slavery after being enslaved with the Maya for several years. She had had to adjust to Maya slavery after living her youngest years as a free Nahua (Mexica is the Nahua tribe which predominated in the Aztec empire)

Her adaptation to the Spanish world was probably made easier because she could communicate with other slaves and Aguilar, who was already in Cortes’s expedition when Malintzin arrived. She showed her agency by being able to adapt to many difficult situations

During her time as a slave, Malintzin befriended Jerónimo de Aguilar (who spent eight years as a slave of the Mayas). Her ability to speak Spanish and her friendship with Aguilar quickly earned her their trust and a special place in the expedition

6 April 1519

Cortés is considering the founding of a town as soon as he finds a convenient place for it. The purpose is not to start building a village but to create a new basis of authority to replace the one given to Cortés by his patron, the governor of Cuba

It would also permit this group of conquistadors to turn themselves into a cabildo (town council) and thereby acquire standing sufficient to make certain kinds of resolutions, laws, and other legally valid decisions, under the direct authority of the crown

Spaniards placed great emphasis on city-dwelling, equating it with civilization, social status, and security. Cortés also needed the direct approval of the crown in order to claim governorship of whatever lands he was able to conquer

7 April 1519

Meanwhile in Tenochtitlan, Moctezuma gave orders to Pinotl of Cuetlaxtlan and to other officials: “Give out this order: a watch is to be kept along all the shores at Nauhtla, Tuztlan, Mictlancuauhtla, wherever the strangers appear.”

Then called his chiefs together; Tlilpotonque, the serpent woman, Cuappiatzin, the chief of the house of arrows, Quetzalaztatzin, the keeper of the chalk, and Hecateupatiltzin, the chief of the refugees from the south

Cortés arrived on the eastern shores of the Aztec empire in the year 1-Acatl. After the conquest, the xiuhpohualli (solar calendar) became tied to the Julian calendar, introducing a leap year to the Aztec calendar every four years. See: https://www.azteccalendar.com

8 April 1519

Charles I of Spain, after the death of his paternal grandfather, Maximilian (12 January 1519) inherited the Habsburg Monarchy. He was also the natural candidate to succeed his grandfather as Holy Roman Emperor. A critical election was underway

The resulting “election campaign” was unprecedented: Charles I of Spain, ‘German by blood and stock’, defeated the candidacies of Francis I of France, Henry VIII of England, and Frederick III, Elector of Saxony. The electors gave Charles the crown on 28 June 1519

Charles was the heir of three of Europe’s leading dynasties: Trastámara of Spain, Habsburg of Austria, and Valois of Burgundy. The personal union under Charles V was the closest Europe has come to a universal monarchy since Charlemagne in the 9th century

Because of widespread fears that his vast inheritance would lead to the realisation of a universal monarchy and that he was trying to create a European hegemony, Charles I of Spain was the object of hostility and prolonged conflicts and wars from many enemies

9 April 1519

Two messengers arrived to Tenochtitlan and went to the House of the Serpent. When Moctezuma appeared, two captives were then sacrificed before his eyes: their breasts were torn open, and the messengers were sprinkled with their blood

When the sacrifice was finished, the messengers reported to the king. They told him what they had seen, and what food the strangers ate. Moctezuma was astonished and terrified to learn how the cannon roared, the smoke that comes out, and the pestilent odor

The messengers also said: “Their trappings and arms are all made of iron. They dress in iron and wear iron casques on their heads. Their swords are iron. Their deer carry them on their backs wherever they wish to go. Their beards are long and yellow.”

When Moctezuma heard the messengers’ report, with its description of strange animals and other marvels, his thoughts were even more disturbed. Days of intense fear and uncertainties were coming to the Aztec empire

10 April 1519

It is Sunday, the Spaniards attend the mass read by Fray Bartolomé de Olmedo. The image of the holy Virgin presided over the mass in the courtyard, where they had erected an altar and a cross

11 April 1519

The invaders remain in occupation of Potonchán and the village renamed Santa María de la Victoria. High above, in the Valley of Mexico, Moctezuma had difficult decisions to make

12 April 1519

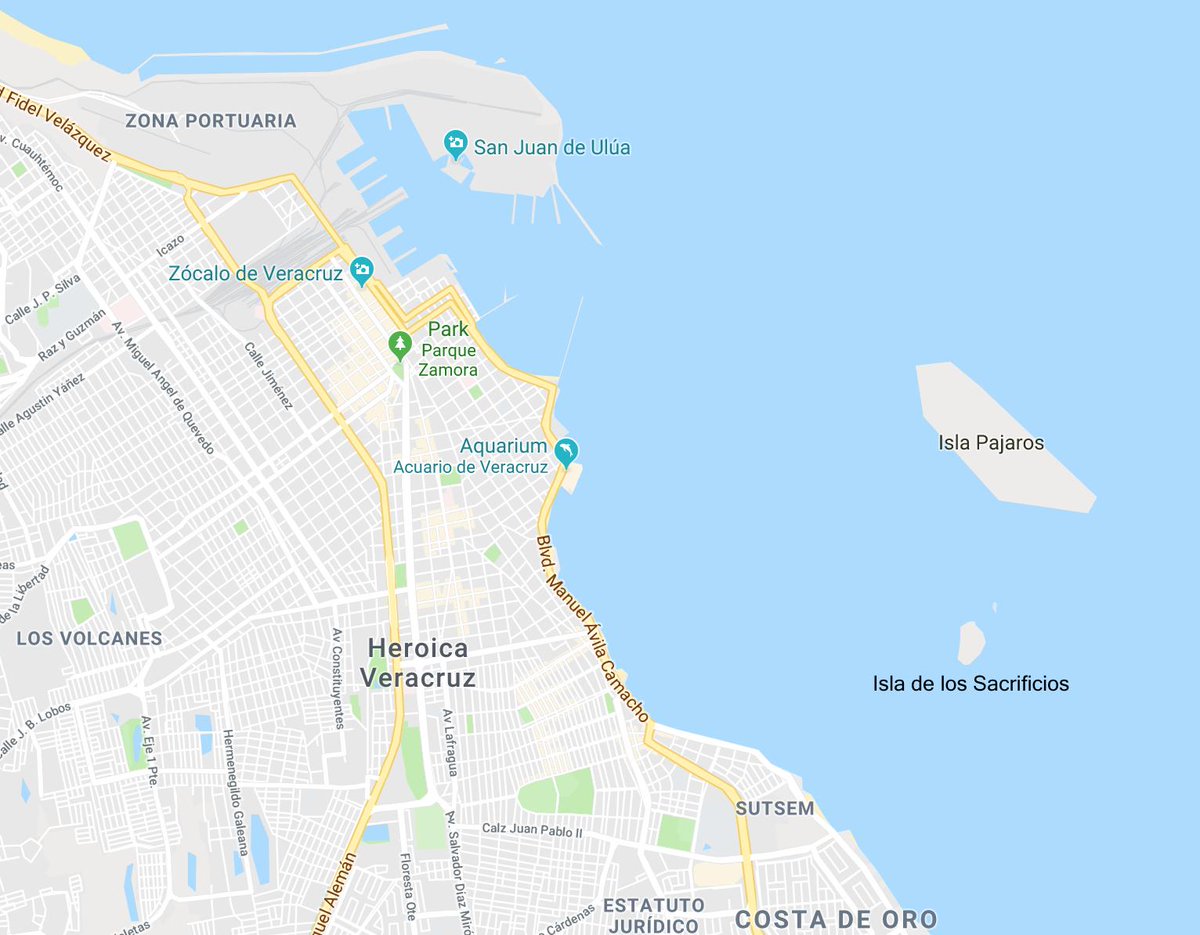

Cortés is waiting for fair winds to set a course to the northwest along the coast, laying tight to shore, heading toward the port that Grijalva, on his previous expedition, had named San Juan de Ulúa (first called the Isle of Sacrifices)

13 April 1519

The ruler of the Aztec empire, Moctezuma II, had succeeded Ahuitzotl in 1502. His power became absolute in the empire, and he soon began subjugating the unconquered peoples of the terrain

However, the Aztec rule over central and southern part of Mexico was not secure, since the domains of the Valley of Puebla and Tlaxcala challenged their authority. In addition, their establishment of rule had only been recently acquired, dating from 1504 to 1516

14 April 1519

From 1503-20, the Aztec Empire suffered a period of tumultuous upheavals; colonized territories struggled for independence and in most cases were brutally subdued. The towns of Quetzaltepec and Tototepec serve as an example of Moctezuma’s brutality

Moctezuma’s army of 400,000 men razed the two towns. The king formed several brigades of warriors, allowing all of his men time to eat and rest. While one brigade stormed Quetzaltepec and Tototepec, the other brigades rested

By the end of the first day of fighting, the cities had been breached. Other Aztec troops approached the Quetzalli River, quickly crossed it in canoes, and took control of the area. Moctezuma’s tactics assured the Aztec a quick and bloody victory

15 April 1519

Context in Spain circa 1519: Nebrija’s rhetoric of the period is an acknowledgement of the role that Spain’s humanist reform might perform in consolidating and complementing the military might of a kingdom destined for further territorial expansion

Nebrija (1444-1522) would celebrate his reforms as a holy war or crusade against intellectual backwardness (‘barbarism’). An emblematic example of this imagery is found in the introduction to the Vocabulario de Romance en Latín from 1516

Here Nebrija would describe his early attempts at Latinate reform in Castile as a crusade against ignorant pagans so as to draw an analogy between his task and that of the apostles Christianizing the ancient pagan world

The reform of Nebrija was followed by the Protestant Reformation, a movement that posed a religious and political challenge to the Roman Catholic church and papal authority in particular: the Ninety-five Theses by Martin Luther in 1517 and the 1521 Edict of Worms

This is an example of what we mean by saying with Elliott ‘we need to set Cortes very firmly into the context of the society from which he sprang, late medieval and early Renaissance Spain, for he at once mirrors the ideals and aspirations of that society’

16 April 1519

As the day following was Palm Sunday, Cortés desired the caziques to come early in the morning to pray before the holy mother of God. He also sent for six Indian carpenters to assist in making a cross on a high ceiba tree near the village of Centla

This cross was made in a manner so as to be very durable, for the bark of the tree, which always grows to again, was so cut as to form that figure. Lastly, Cortes desired the Indians to bring out all their canoes in order to assist us in reembarking

For Cortés was desirous of setting sail on that holy day, as, according to pilot Alaminos, their present station was not secure from the north winds.

17 April 1519

Palm Sunday. Early in the morning the caziques and the principal personages, all with their wives and children, made their appearance in the courtyard, where Cortés had erected the altar and cross, and collected the palm branches for the procession

Father Bartolome de Olmedo, belonging to the order of the charitable brethren, and Juan Diaz, were dressed in their full canonicals, and read mass. We prayed before the cross and kissed it, the caziques and Indians all the while looking on

The principal Indians brought ten fowls, baked fish, and all kinds of greens. Cortés recommended them to take care of the image of the holy Virgin and the cross, and to hold the chapel in due reverence, in order that salvation and blessings might come upon them

All expeditioners embarked in the evening. Cortés thanked the Tabascan chiefs, loaded the gifts of food, gold, and the slave girls, and readied to set sail for the north. They would search for and find this place called “Mexico.”

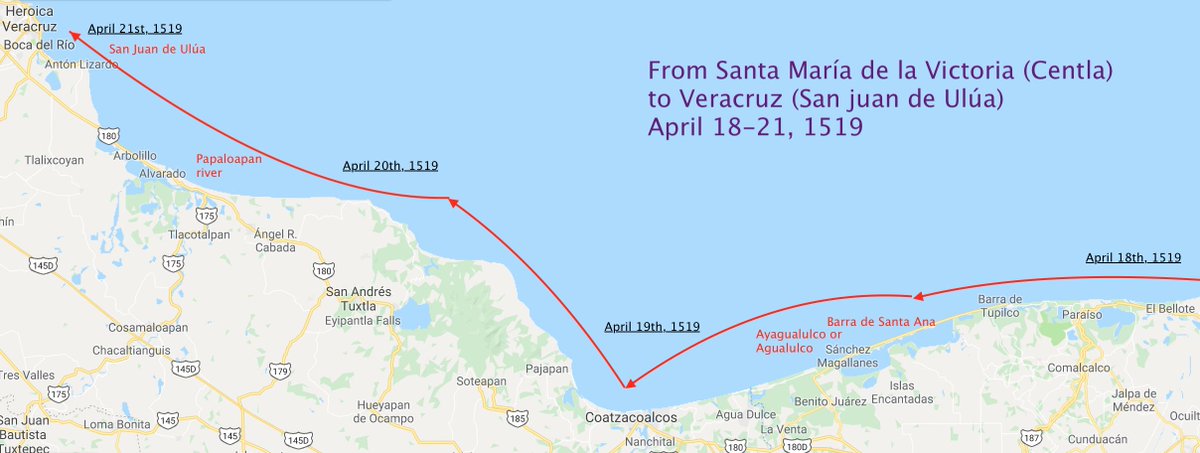

18 April 1519

On Easter Monday morning Cortés set sail with a good wind. They always kept close to the shore, and steered in the direction of San Juan de Ulúa. They coasted along for three days, the weather being most favorable

Bernal Diaz: “We who had been here with Grijalva, and were well acquainted with these parts, pointed out to Cortés La Rambla, which the Indians call Ayagualulco; the coast of Tonalá or San Antón, the great river Guazacualco (Coatzacoalcos), the snow mountains”

“And those of San Martin, the split rock forming two points, which stretch out into the sea, and somewhat resemble the figure of a chair. We then showed him the river Alvarado (now Papaloapan river), further on the river Banderas, where we made the 16000 pesos”

“The Isla Blanca and Isla Verde, also the Isla de Sacrificios, where, under Grijalva, we found the idols with the Indians who had been recently sacrificed” See geographical references in https://bit.ly/2VSVxkk

19 April 1519

Under fair winds, the entire fleet set a course to the northwest along the coast, laying tight to shore, watching the coast of Tonalá and the great Coatzacoalcos river. Cortés, on the Santa María de la Concepción, continued to scan the shoreline

20 April 1519

Cortés’ fleet progressed westward arriving to Rio de Alvarado, now Papaloapan river, on the border between the states of Veracruz and Oaxaca. Its name comes from the Nahuatl “papaloapan” meaning “river of the butterflies”

21 April 1519

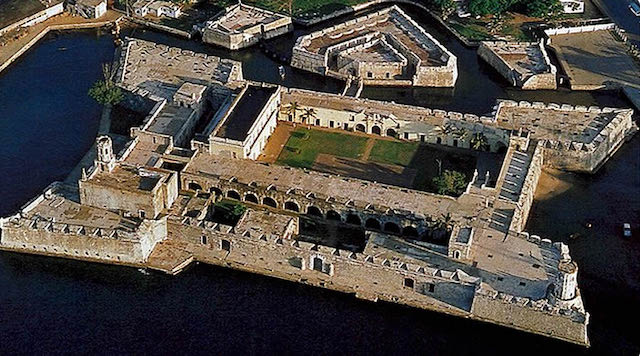

Holy Thursday. The fleet drops anchor in the harbor of San Juan de Ulúa, all anchored close by, protected from strong northerly winds. Cortés ordered Spanish pennants and royal flags raised on the Santa María de la Concepción

Shortly after, a boat bearing two subordinates of the regional Aztec administrator Teutliltzin (also rendered as Teudile or Teudilli) contacts the visitors inquiring as to their intentions

Bernal Díaz: “Alaminos brought our ships to anchor in a place where they were sheltered from the north wind. We had scarcely lain here half an hour when we saw two large canoes, which are called here pirogues…”

“filled with a number of Indians, making straight for Cortés’ s vessel which” from the large flag hanging from the mast-head, they recognized as our

commander’s ship. They climbed on board without any ceremony, and inquired for the Tlatoan, which means master.”

“Doña Marina understood their question, and pointed to Cortés; they, therefore, turned to him, paying him great reverence after the Indian fashion, and bid him welcome. Their master, they said, who was a servant of the great Moctezuma, had sent them”

“…in order to ascertain who we were and what we came to seek in his country. We had only to inform them of what we wanted for our ships, and they would see that it was provided. Cortes thanked them for their kindness, through Aguilar and Doña Marina”

“…presented them with some blue glass beads, and ordered some meat and drink to be placed before them. After they had taken some refreshment, he told them we were merely come here to make their acquaintance, and open a trade with them”

“…we had not the remotest intention of doing them any injury, nor need they apprehend anything from our arrival. The ambassadors now returned, well contented, to their homes”

22 April 1519

Good Friday. Cortés ferries his army ashore, complete with horses and cannon, and has his Cuban laborers swiftly fell trees and erect a fortified camp opposite San Juan de Ulúa. The Spaniards are given a friendly reception by the local Totonacs

Mesa, the captain of artillery, placed the cannon on a very advantageous spot, and they erected an altar where mass was immediately performed. For Cortés and the other chief officers huts were constructed of green boughs

23 April 1519

Holy Saturday. In the morning, emissaries began to arrive at the Spaniards’ makeshift camp. The first group claimed to have been sent by their leader Cuitlalpitoc (incidentally, the same man who had been sent to parlay with Grijalva)

Through Aguilar and Malintzin Cortés first heard utterance of the name Moctezuma. Aguilar spoke Mayan and Spanish. Malintzin spoke Mayan and Nahuatl. So, they translated Nahuatl <-> Mayan <-> Spanish. Through Aguilar Malintzin learnt Spanish with remarkable speed

This man Moctezuma was said to be the powerful ruler of the Mexica, a feared Triple Alliance of the city-states Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tacuba, who inhabited the Valley of Mexico. Cortés listened carefully, receiving Cuitlalpitoc with kindness and hospitality

More ambassadors arrived bringing elaborate gifts, including a crafted feather garment, a war shield inlaid with opalescent mother-of-pearl, and a lot of food. They said that Cortés should expect a visit soon from a very important governor of Moctezuma, then left

24 April 1519

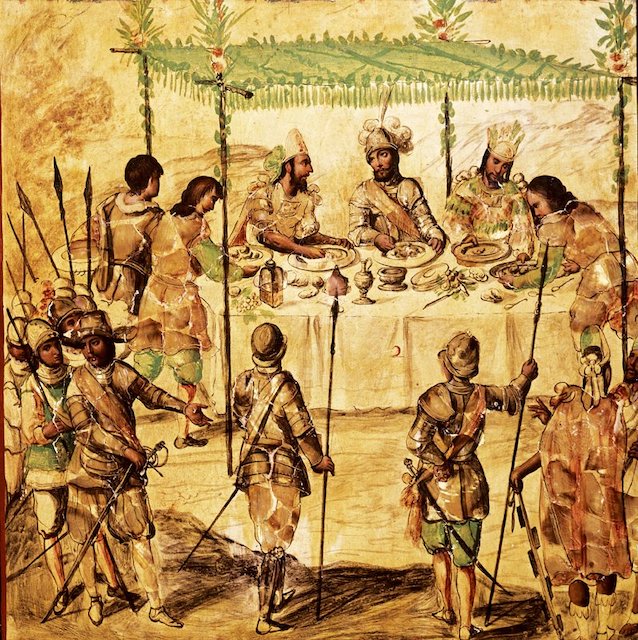

Easter Sunday. The ambassador Tendile (Teutliltzin) arrived as promised with a few thousand attendants in tow, all dressed in feathered finery and elaborately embroidered cloaks, nobles carrying gifts and provisions

Fray Olmedo read mass, which Tendile and his nobles listened to with great curiosity and interest. After that, Tendile followed with a ritual of his own, as he and some other noblemen performed a “dirt eating” ceremony

In the ceremony, they dampened their fingers, touched them to the earth, then placed the dirt-smudged fingers to their lips in a show of respect. They handed Cortés sticks of burning incense and reeds dipped in their blood

Tendile then brought forth bearers carrying great chests, from which he proffered gifts from the great Moctezuma, his emperor from high above and far away in the mountains, a deeply feared and sovereign leader who ruled from the capital city, called Tenochtitlán

Cortés told Tendile that he too served a most powerful king, one who lived across the vast seas to the east, and that his own king knew well of the great Moctezuma. Cortés added he had instructions to meet personally with Moctezuma and would expect nothing less

Cortés noticed the concerned expression on Tendile’s face when he learned of this ruler from the east, for there existed a myth proclaiming that very thing: the return of the god Quetzalcoatl coming from the east

For the moment, though, Tendile simply nodded and spoke to one of his attendants, who was sketching furiously on a large canvas made from the dried and stretched flesh of the maguey plant

Cortés inquired about it, and Tendile informed him that this was “picture writing,” and that his painters were recording all the proceedings, so that they could report accurately to Moctezuma what they had observed and learned

Bernal Díaz remembered that Tendile gave his painters instructions “to make realistic full-length portraits of Cortés and all his captains and soldiers, also to draw the ships, sails, and horses, Doña Marina [Malintzin] and Aguilar, and even two greyhounds.”

Cortés then ordered an impressive, awesome display of power that quite literally put the fear of god in Tendile and his men, for indeed the weapons and the animals possessed such power and novelty that Tendile wondered if these creatures might be teules—gods

Tendile then inquired about a particular helmet worn by one of the Spaniards who had been performing military exercises on the beach. He noted that this helmet possessed a resemblance to those worn by their war gods, including Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl

Cortés responded that Tendile could certainly take the helmet under the condition that it be returned filled with grains of Aztec gold, which he might compare with that of his homeland in Spain and give as a gift to his own great monarch across the eastern oceans

Of his desire and interest in Aztec gold, Cortés added that “I and my companions suffer from a disease of the heart which can be cured only with gold.”

(Cortés could have previously learned about Huitzilopochtli, the highest deity in the Aztec pantheon, and its insatiable hunger for blood and human hearts. Then he elaborated the story of the disease of the heart and the need for gold as a cure)

Tendile departed, assuring the captain that his people would supply the visiting Spaniards with food on the beach and that he would soon return with a response from his ruler in Tenochtitlán

As a generous parting gift, Tendile had left Cortés with some two thousand servants, workers instructed to construct hundreds more huts and shelters for the Spaniards. They also offered women to make maize cakes and cook fowl and fish, which they provided daily

25 April 1519

The report of the Spaniards coming to the shores was brought to Moctezuma, who immediately sent out messengers. It was as if he thought the new arrival was their prince Quetzalcoatl

This is what Moctezuma felt in his heart: He has appeared! He has come back! He will come here, to the place of his throne and canopy, for that is what he promised when he departed! (Codex Florentino)

Moctezuma sent five messengers to greet the strangers and to bring them gifts, led by the priest in charge of the sanctuary of Yohualichan. The second was from Tepoztlan; the third, from Tizatlan; the fourth, from Huehuetlan; and the fifth, from Mictlan the Great

Moctezuma said to them: “Come forward, my Jaguar Knights, come forward. It is said that our lord has returned to this land. Go to meet him. Go to hear him. Listen well to what he tells you; listen and remember.”

26 April 1519

Moctezuma gave the messengers his final orders to meet the strangers: “Go now, without delay. Do reverence to our lord the god: Say to him: Your deputy, Moctezuma, has sent us to you. Here are the presents with which he welcomes you home to Mexico”

(Interestingly, it seems Moctezuma and the founder of Spanish Guardia Civil, the Duke of Ahumada, are related: https://bit.ly/2FIDYxP . A family history that is an example of how the Mesoamerica elites were involved with the Spaniards’ ones for almost 300 years)

****************************

Comentarios y otros tweets que reflejan mi idea:

In addition to wars, epidemics and terrible crimes, the Spaniards brought with them civilization, universities, language, religion, laws, etc. It was like the Roman Empire for Western Europe. When did the United States or the British Empire behave like this?

Cortés changed the entire Aztec world, but he also created a new one, and for this he used more intelligence than a dragon. Spain destroyed, but it also invested men and resources to build a new civilized world for almost 300 years

Many complex civilizations have been replaced throughout history. In my opinion, what is unique in Mesoamerica is the joint development, driven by Spain, and the creation of a new world following Western standards, for better or for worse

****************************

27 April 1519

Learning that the visitors wish to meet the Emperor Moctezuma II at his capital of Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City), Teutliltzin sends a request and other reports inland by messenger, while assigning 2,000 native tributaries to wait upon the Spaniards

28 April 1519

Cortés and Malintzin were developing something more than just good rapport. She had been at Cortés’s side since the moment he discovered her linguistic prowess, and she would remain there for the duration of the expedition

29 April 1519

The symbol of the Fleur de Lis changed the course of New World History. A surprising confluence of religious ideas recognized in both the Old and New World and symbolized by the trefoil design we know as the Fleur de lis

In both hemispheres the Fleur de lis symbol is associated with divine rulership, linked to mythological deities in the guise of a serpent, feline, and bird, associated with a Tree of Life, it’s forbidden fruit and a trinity of creator gods

In Mesoamerica, as in the Old World, the royal line of the king was considered to be of divine origin, linked to the Tree of Life

Descendants of the Mesoamerican god-king Quetzalcoatl, and thus all Mesoamerican kings or rulers, were also identified with the trefoil, or Fleur de lis symbol. Read the article by Carl de Borhegyi

30 April 1519

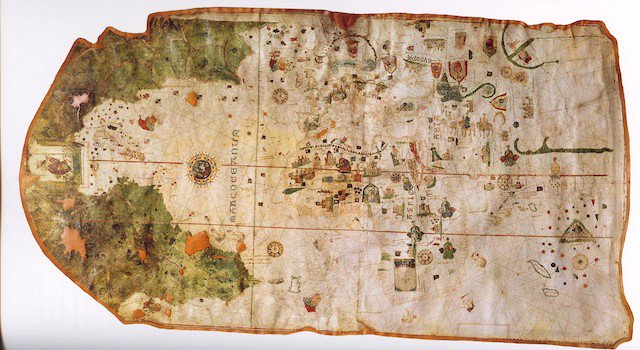

A trip around the world of 1500. The Universal Nautical Chart of the Spanish navigator and cartographer Juan de la Cosa (c. 1450 – 1510), the first cartography of the Americas (Image rotated to match modern map orientation) – see link

It constitutes the maximum expression of the knowledge of the world towards year 1500. Its political importance probably was worth the classification as Secret of State on the part of the Catholic Kings. See link to Spanish Naval Museum

1 May 1519

In the Crónica Mexicana, by Tezozomoc (1598), Moctezuma, believing that the men who’d embarked on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico were messengers from the god Quetzalcoatl – who, according to Mexican myth, would return to govern his people – sent…

… his own men to receive them, loaded with presents. Tezozomoc ofers a detailed list of the gifs sent for this frst interview: maize, chile, tamales and “all manner of food, very well-made tamales, sent still hot, ordinary tortillas and tamales with beans, …

.. round like thick rods, and all sorts of cooked and grilled fowl, quail, barbecued deer, rabbits, ground chile, many kinds of cooked quelites or greens, and fruits like plantains, custard apples, guavas and chayote squash” (Tezozomoc, see link)

Read Crónica Mexicana, edited by G. Díaz Migoyo, online in Spanish: see link to this book

2 May 1519

About eight days after their first encounter, Tendile returned from Tenochtitlan leading a retinue of over one hundred bearers, strung in a long line behind him, and accompanied by a person of distinction named Quintalbor, who greatly resembled Cortés

For this reason, Quintalbor had been selected by Moctezuma to accompany the deputation; for, when Tendile brought forth the picture representing Cortés, all the grandees who were present with Moctezuma, immediately observed that Cortés resembled Quintalbor

Arriving before Cortés, Tendile and Quintalbor kissed the earth and perfumed the Spaniard and the soldiers around him with smoke from incense burning in earthen braziers. Then Tendile’s attendants laid out numerous woven presentation mats called petates

Then, they spread generous gifts from Moctezuma himself: plates and sandals, all of pure gold, and a strung bow and a dozen arrows of solid gold. They set out two enormous plates of gold and silver which were according to Bernal Díaz “as large as carriage wheels”

3 May 1519

One of these impressive disks represented the sun, the heavy gold carved elaborately with depictions of plants and animals; the silver plate, slightly larger, symbolized the moon

Cortés marveled at the intricately woven and resplendently dyed cotton garments, cloaks of featherwork of inestimable beauty , created by highly skilled craftsmen. The jewelry—gold collars and necklaces and bracelets—was inlaid with shimmering precious stones

Also on the mats were laid golden deer and ducks and dogs, jaguars and monkeys and fish, golden rods and staffs. The Mexicans presented the helmet Tendile had taken, filled as requested with gold flakes and nuggets directly from the mines

Cortés stood amazed before the generous and wondrous artifacts, conscious for the first time that he was dealing with people of a highly civilized and established culture who could mine and then intricately fabricate precious metals

Tendile, seeing that Cortés was pleased, paused to let his pleasure sink in. Then he intimated Moctezuma’s wishes and his message: with great pleasure he offered these gifts to Spain’s king, and he was happy to have this direct communication

But Moctezuma would not come personally to see them, and under no circumstances could they visit him. Moctezuma’s instructions were polite but specific: the Spaniards were to take his gifts as gestures of good faith and evidence of his wealth and power— and leave

Moctezuma’s gifts had also piqued the greed and desire of the Spaniards. Seeing this imperial haul, Cortés had no intention of leaving. He remained calm in his dealings with Tendile, and decided to push him saying that his own king would be unhappy with him

He thanked Tendile profusely for the gifts but wished him to return once more to Moctezuma and express his deep desire for a meeting. He presented for Moctezuma several tokens of his great respect

These included a number of Dutch shirts woven of fine linen, a Florentine glass goblet engraved with scenes of hunting, and handfuls of glass beads. Cortés gave what he could and sent Tendile away, still hoping for a personal audience.

4 May 1519

Once Tendile left, Cortés assessed their situation on the dunes. It was untenable. The sands grew scorching hot during the day, and the area was surrounded by stagnant marshes that produced thick clouds of flies, gnats, and mosquitoes

Many of his men were racked with stomach cramps and bowel disorders, some even succumbing to tropical bilious fever. So far some thirty of his men had perished from battle wounds and diseases. What food they had was spoiling in the hot sun or in the ships’ holds

Perhaps even worse, there were grumblings of discord among his men; some suggested that they should take the gifts and return immediately to Cuba. Cortés dispatched two expeditions—one over land and one by sea—to discover a more suitable location for settlement

He sent two brigantines, one piloted by Alaminos and captained by his own loyal friend Rodrigo Álvarez, the other under the captaincy of a Velázquez supporter named Francisco de Montejo, manned by some fifty soldiers, nearly all devoted to the governor of Cuba

As it turned out, Cortés’s choice to send away the bulk of the Velázquez sympathizers appears not to have been accidental. Álvarez and Montejo were to seek a better harbor and a landing site that was not plagued by lowland marshes, swamps and the attendant swarms

Cortés assigned Juan Velázquez de León, a relative of Velázquez, to foray into the interior for three days, also in search of more favorable surroundings for settlement and fortification

5 May 1519

In the Valley of Mexico, Moctezuma had difficult decisions to make. Deeply spiritual, having been a high priest before becoming emperor, his priests suggested that the invading Spaniards be driven back to where they came from or, better yet, killed

He learned from his spies and emissaries that along his route Cortés and his men had been destroying temples and replacing native idols with their own. Moreover these Spaniards were strangely served by beasts and they carried fire and thunder in their hands

Tradition held, and Moctezuma fully believed, that the Aztec capital was the sacred center of the universe, and spiritual epicenter of his vast empire, but he feared also that the arrival of this Cortés was predestined

The myth of Quetzalcoatl told that the bearded royal ancestor would one day arrive to “shake the foundation of heaven” and conquer Tenochtitlán. Moctezuma listened to his priests and mused

6 May 1519

Cuitlalpitoc, who had remained to furnish Cortés and his men with provisions, soon ceased to do so altogether, which, of course, created a great scarcity of food: their cassave-bread had likewise become quite mouldy and swarmed with worms

Now they had to procure food by themselves. Indians no longer came in such great numbers as at first, and those who did come appeared quite shy and reserved. Cortés expedition, therefore, anxiously awaited the return of the two ambassadors from Tenochtitlan

7 May 1519

Moctezuma chose two of his trusted nephews and four of his priests (Tendile among them) and sent them again to the coast. They were to deploy spies to monitor all subsequent movements of the Spaniards and report back by means of their best “runners”

The painanis were runners, relays of men who ran with astonishing speed and stealth through the thin mountain air, able to travel and dispatch messages across distances up to two hundred miles per day