1519 Timeline from 1 November (Paso de Cortés) to 8 November (Tenochtitlán)

Approximate route (version 1.1) followed by Hernán Cortés from Zempoala (16 August 1519) to Tenochtitlan (8 November 1519) #TheMeeting See in Google Maps: https://bit.ly/33WV7hp

1 November 1519

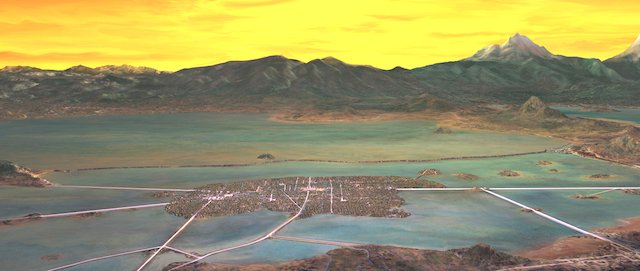

By morning snow covered the ground, but the storm had subsided and the skies cleared. Cortés mustered and marched, and soon the group arrived at the top of the descent into the other side, overlooking the Valley of Mexico

Mist lifted like steam from the valley floor and afforded them views that left them breathless: the connected lakes and waterways glinting in the sun like iridescent blue gemstones, and houses magically built on them, and white trails of wood smoke lofting up from the many whitewashed houses that stretched out for miles

Surrounding and outlying the cities on the lakes were manicured, cultivated jade-colored fields of beans and maize, and beyond them, Tenochtitlán itself—grander and higher and larger than the other cities—seemed to float upon Lake Texcoco

They took it all in, amazed and even reverent, for they had never seen anything of its kind before, and many were left to simply gape in awe and wonder as they descended the steep switchback trail down into the valley

2 November 1519

Cortés descended into the valley, passing through beautiful woods and small villages and eventually arriving at a town called Amecameca, home to nearly five thousand people

During their descent they were also visited by yet another embassy of Aztecs, this one special, for Moctezuma had included a handful of his best magicians and sorcerers who he hoped might be able to thwart the relentless approach of the Spaniards

The Aztecs reported that “Moctezuma sent the magicians to … see if they could work some charm against them, or do them some mischief… or to direct a harmful wind against them, or cause them to break out in sores, or injure them in some way.”

Moctezuma, running out of options and apparently becoming desperate, also sent an impersonator, a nobleman named Tziuacpopocatzin. He was to dress in regal finery, assume a kingly countenance and behavior, and claim to be Moctezuma

The idea being that they could hold their formal meeting and then, just maybe, the Spaniards would turn back. They came bearing a good deal of gold, which sent the captains into a sort of delirium apparently still giddy from their high-altitude trek

Sahagún recorded their response, saying they clung to the gold “like monkeys… they thirsted mightily for the gold, they stuffed themselves with it, and starved and lusted for it like pigs. They … showed it to one another, all the while babbling”

Initially the Spaniards believed that the nobleman Tziuacpopocatzin might be Moctezuma, for he claimed to be, but after consulting a number of the Tlaxcalans, Cortés determined that the man was of the wrong age and build, and the ruse was discovered

The magicians and wizards, too, failed in their attempts, and the embassy returned to Moctezuma with disconcerting news: all their witchcraft, spells, and conjurings were ineffective on these teules, these gods

Cortés, his cavalry and horses, and many thousand Tlaxcalans were still coming to Tenochtitlán. Moctezuma sought more counsel, both from his priests and from his gods

3 November 1519

Cortés remained in Amecameca for two full days, where he was well treated and given gold as well as forty slave girls. He developed good relations with the city’s chiefs assuring them that soon he could help them against the Aztecs.

4 November 1519

At noon the expedition arrived to Tlalmanalco, where they met with very kind and hospitable treatment. Several neighboring tribes made them a present in common, saying: “from this moment we hope you will look upon us as your friends!”

5 November 1519

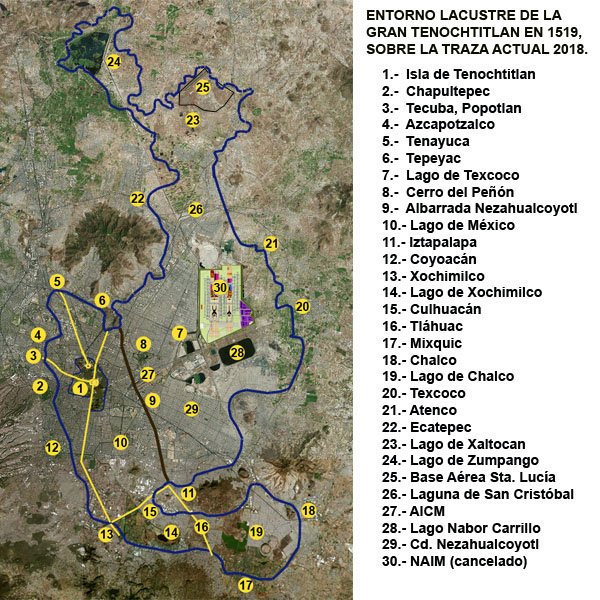

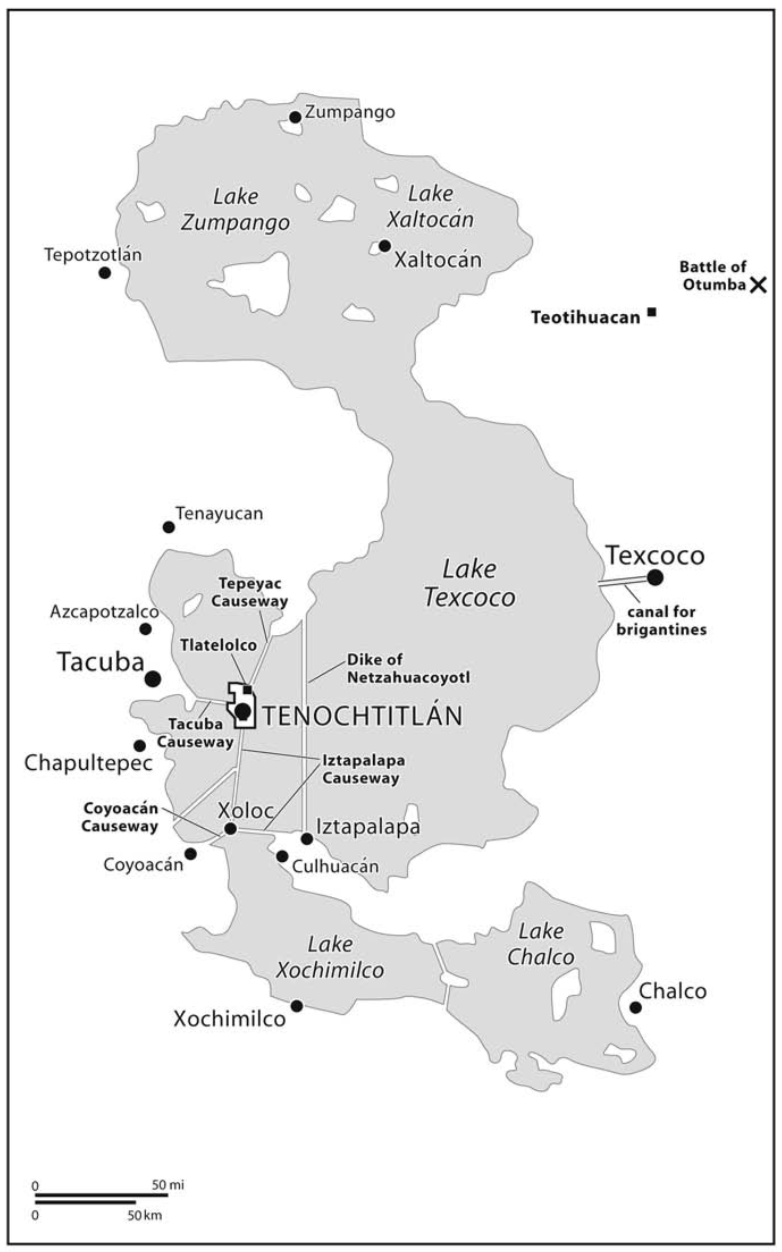

Cortés arrived at the banks of Lake Chalco, the southernmost body of water in the lacustrine chain. The Spaniards watched with interest the many canoes pouring into and out of the town on the calm waters

Soon a very formal and official contingent of Aztec nobles arrived bearing with them Cacama, Moctezuma’s nephew and king of Texcoco. Cacama faced Cortés and explained that he regretted the Huey Tatloani was unable to come himself but he felt ill

Cacama wished to extend every courtesy to Cortés and his men, who would have a personal audience with Moctezuma very soon. Until then, Cacama and his nobles and lords would escort the Spaniards to the city of Iztapalapa, and then into the capital

Hearing this message and overcome with emotion, Cortés embraced the prince in an awkward (but customarily Spanish) hug, then hung from him a necklace of cut glass. He gave colored beads to the other attendees standing by

6 November 1519

Cortés followed Cacama along the lakeshore. Soon they encountered the first of the marvelous causeways, a long straight road structure made of stone that ran some 5 miles across the water from Chalco to the adjoining Lake Xochimilco

They marched in growing awe and wonder as they neared the town of Cuitláhuac, which Cortés described as “the most beautiful we had seen, both in regard to the well-built houses and towers and in the skill of foundations, for it is raised on the water”

Bernal Diaz: “When we saw all those cities and villages built in the water . . . and that straight level causeway leading to Mexico, we were astounded. These great towns and temples had buildings rising from the water, all made of stone. It seemed like an enchanted vision… Indeed, some of our soldiers asked if this was not all a dream.”

Cortés himself would refer to Tenochtitlán as the City of Dreams, exclaiming that it was without question “the most beautiful thing in the world”

7 November 1519

When they arrived at Iztapalapa, Cortés was utterly impressed. The city was constructed next to a vast salt lake, half on land and the other half suspended on foundations and pylons seeming to hover over water (map from Buddy Levy)

It was the domain of Cuitláhuac himself, brother of Moctezuma and Cacama’s uncle. Cuitláhuac was an experienced warrior and warned Moctezuma not to allow the Spaniards to enter Tenochtitlan. Eventually he succeeded Moctezuma in 1520 for just 80 days

Cuitláhuac invited Cortés and his men to stay there for the night. They were shown about the nobles’ villas, many newly constructed, multistoried, and complete with kitchens and outdoor terraced gardens connected by stone corridors lined by trees

The courtyards and corridors were covered with awnings made of woven cotton, for shade and shelter. Cortés remarked that the craftsmanship and design surpassed anything in Europe. Next morning Cortés would finally meet Moctezuma

8 November 1519

Cortés gathered his troops and fitted them out in their most impressive battle regalia, determined to march into the city in impressive fashion, but also because they would be exposed along the five-mile causeway

Nine months after sailing from Cuba and after three months of forced marching and fighting since leaving Villa Rica, Cortés had arrived at the gates of the Aztec empire, alongside Malinche

The ride in brought Cortés at last to a fortress bordered by two great towers. Moctezuma’s welcoming ambassadors led Cortés over a drawbridge to the main island and the gates at the heart of the city of Tenochtitlán

The stage was set for a moment unprecedented in human history: a meeting between two civilizations, two completely autonomous worlds with no prior encounters or understanding of each other

Cortés shifted in his saddle and eyed the gates, the crenellated battlements, and the rooftops of the houses overflowing with onlookers; he realized that he was utterly exposed here, his military position less than tenuous

He could not believe, despite everything he had been told about Tenochtitlán, the size and scope and grandeur of the place. He and his company, against great odds and perhaps against good judgment, had ridden into the most powerful and most populated city in the Americas, perhaps even in the entire world, and they were now surrounded by water on all sides. All he had left to do now was wait for Moctezuma and see what would transpire

Cortés looked up to see two long processions of people approaching. They were elaborately dressed Aztec nobles bedecked in ornately feathered headdresses, their dyed cotton garments embroidered with gold

In the center four noble attendants bore a gold-plated litter, its awning adorned with brilliant quetzal feathers and lined with silver, gold, gemstones, and pearls

Cortés dismounted as the attendants came to a halt, and from the litter the great monarch Moctezuma emerged and stepped down onto cloaks laid at his feet so that they would not have to touch the ground

Cacama and Cuitláhuac walked next to Moctezuma, followed by other lords of local tributaries. Though the others were barefoot, Moctezuma wore gold-soled sandals, the jaguar-skinned thongs bejeweled with precious stones

As they came face to face for the first time, the two regarded each other. Cortés observed a man five years his senior, regal, perhaps softened from the indulgences of kingship, but lean and dark, his black hair cropped tight

He wore a brilliant green quetzal feather headdress and an embroidered cotton cloak studded with jewels. His lower lip was pierced with a blue stone hummingbird, his ears with turquoise, and his nose with deep green jadestone

In Cortés, Moctezuma beheld a bearded man hardened by recent toil and battle, his white face and limbs scarred, his eyes defiant. There was an awkward pause, during which Moctezuma leaned forward to smell Cortés

Cortés would later say of the exchange: “I stepped forward to embrace him, but the two lords who were with him stopped me with their hands so that I should not touch him.”

Cortés inquired directly to the emperor: “Are you Moctezuma?” With measured calm came the reply, “Yes, I am he.” The emperor said to Cortés: “You are weary. The journey has tired you. But now you have arrived… Rest now.”

Moctezuma then took his leave, climbing again into his litter to be borne back to his palace. Cacama led Cortés and his company to their accommodations. The Spaniard thanked the emperor saying: “Tell Moctezuma that we are his friends.”

Cortés lodged in the Palace of Axayacatl, Moctezuma’s father. Across the way, to the east, Cortés could see the city’s ball court, and beyond, the sacred precinct including the Great Temple (Templo Mayor)

Later in the afternoon, after Cortés and his men had supped on fowl and tortillas, Moctezuma summoned his visitor, his chosen captains, and Malinche and Aguilar into the great hall of the palace

The emperor took his seat on a throne and seated his guest next to him on another throne. There Cortés received a lengthy procession of gifts, constituting an immense display of Moctezuma’s wealth and power including more gold and silver

Moctezuma addressed Cortés with great formality and measured, even poetic language, conveying through Malinche a speech that will remain among the most perplexing, and intriguing in history, the subject of endless interpretation

The Nahuatl version, gleaned from oral histories, translated into English says: “O our lord, you have suffered fatigue, you have endured fatigue. You have come to reach the earth. You have come to govern your city of Mexico”

“You have come to descend on your mat, on your seat, which I have observed for a moment, which I have kept for you. Because your governors left: the Itzcoatl, Moctezuma the older, Axayacatl, Tizoc, Auitzotl rulers (…)”

“The rulers left maintaining that you would come to visit your city (…) now it has been fulfilled; You’ve come; You have endured fatigue. Peace be with you. Rest yourself. Visit your palace. Rest your body. May peace be with our lords”

Cortés would later interpret the great lord’s words literally rather than figuratively (as they likely were meant) and assume that Moctezuma believed the prophecy, that Cortés had returned to assume the mantle of his authority

Cortés’s response, through Malinche, was clipped and clever: “Let Moctezuma put his heart at ease. Let him not be frightened. We love him much. Now our hearts are indeed satisfied, for we know him, we hear him (…)”

Moctezuma closed the encounter by inviting Cortés and his men to roam the city freely, with Aztec guides, and behold its magnificence. Then he retired to his own quarters for prayer.

In 1992 Lorenzo Ferrero composed La ruta de Cortés, a symphonic poem which can be performed individually or as part of the suite La Nueva España.