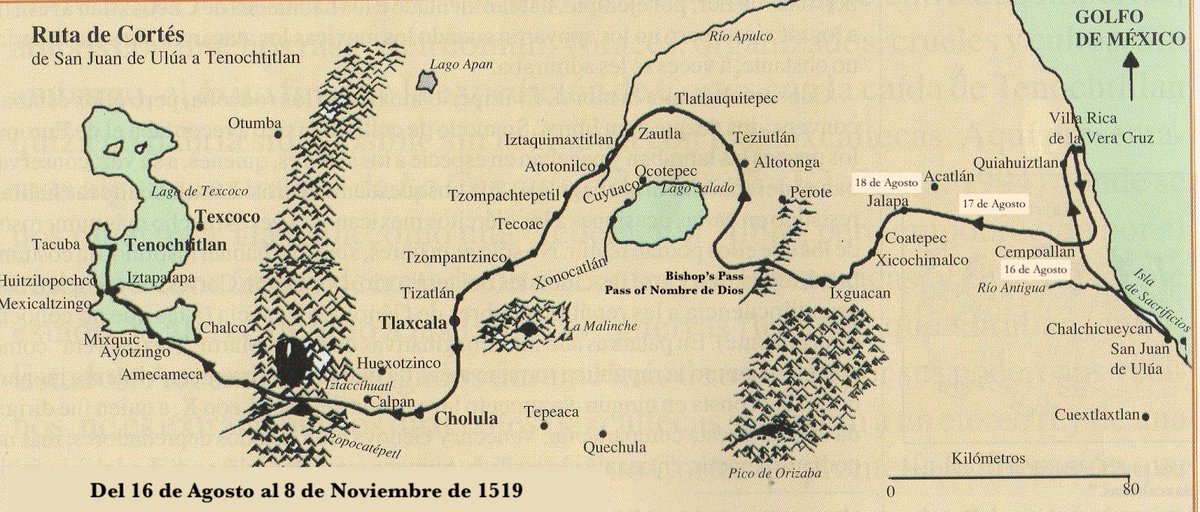

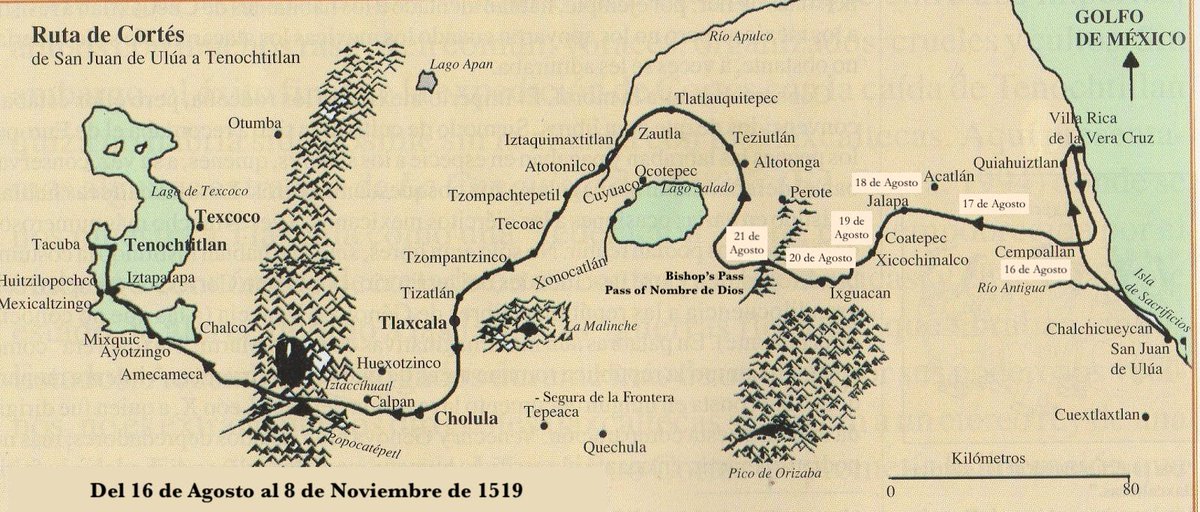

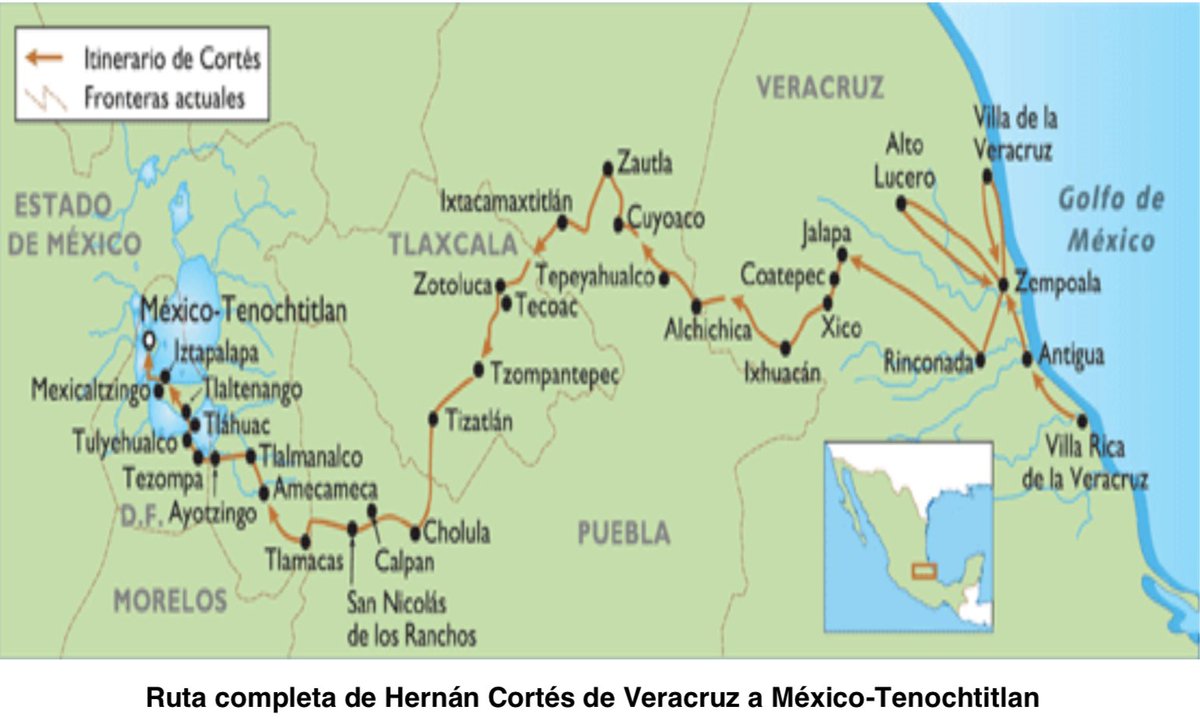

1519 Timeline from 16 August (leaving Veracruz) to 31 October (Paso de Cortés)

Approximate route (version 1.0) followed by Hernán Cortés from Zempoala (16 August 1519) to Tenochtitlan (8 November 1519) #TheMeeting See in Google Maps: https://bit.ly/33WV7hp

16 August 1519

During the first day, their road lay through the tierra caliente, the beautiful land where they had been so long lingering; the land of the vanilla, cochineal, and cacao

They marched westward, in the direction of Jalapa. Fit and knowledgeable Totonac scouts ran ahead on reconnaissance forays, returning periodically to report to Cortés the lay of the land and any hostile movements among the native populations

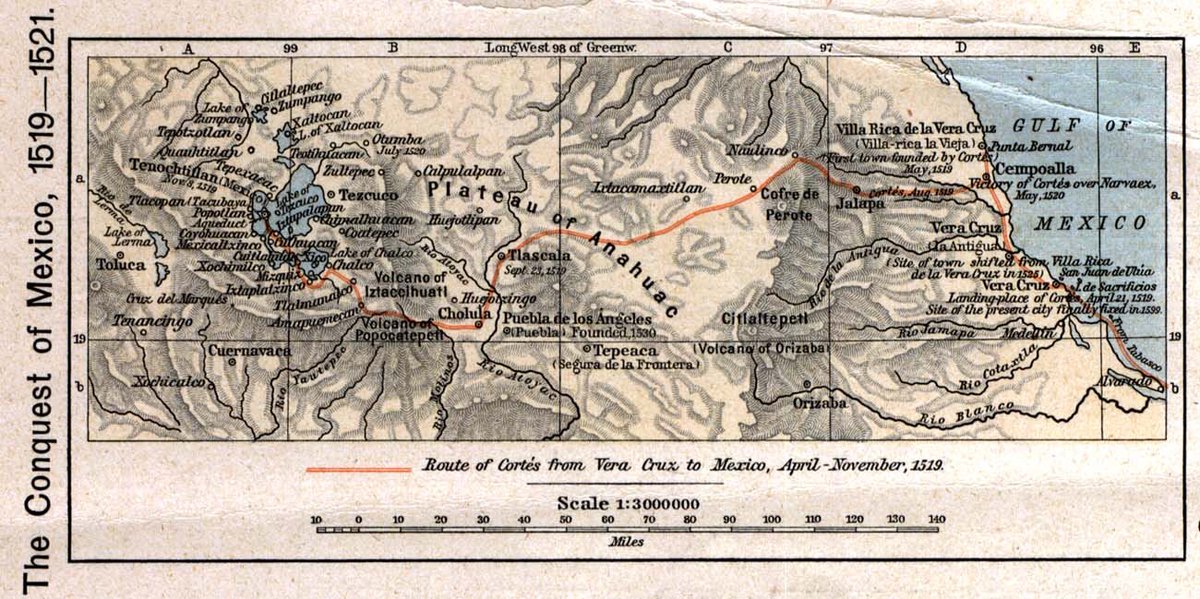

(One of the many maps showing an inexact route of Cortés to Tenochtitlán. This is from the XIX century)

17 August 1519

After some leagues of travel over roads made nearly impassable by the summer rains, the troops began the gradual ascent which leads up to the table-land of Mexico. The air thinned and cooled as they rose to 4000 feet

To the southwest Cortés and his men stared in wonder at the gigantic, snowcapped dome of Orizaba, soaring nearly 9000 feet above sea level, called “Star-Mountain” by the Mexicans (Citlaltépetl and also Iztactépetl, white mountain)

After two days of forced marching on trails choked with thorny vines and grandillas, or passion flowers, they reached the town of Xalapa, at the far reaches of the Totonac boundaries. There they rested for the night, being well treated, then kept on

18 August 1519

Still winding their way upward, amidst scenery as different as was the temperature from that of the regions below, Cortés’s army passed through settlements containing some hundreds of inhabitants each

Nuestra Señora de Asunción de Panamá (Panama Viejo), was founded by Pedro Arias de Ávila, gobernor of Castilla del Oro, on 15 august, 1519. Panama city was the starting point for expeditions that conquered the Inca Empire in Peru

It was a stopover point on one of the most important trade routes in the American continent, leading to the fairs of Nombre de Dios and Portobelo, through which passed most of the gold and silver that Spain took from the Americas

19 August 1519

On the fourth day Cortés reached a “strong town” standing on a rocky eminence. Here they were hospitably entertained by the inhabitants, who were friends of the Totonacs

Cortés endeavored, through father Olmedo, to impart to them some knowledge of Christian truths, which were kindly received, and the Spaniards were allowed to erect a cross in the place, for the future adoration of the natives

Indeed, Cortés’s route might be tracked by these crosses, raised wherever a willing population of Indians invited it, suggesting a very different idea from what the same memorials intimate to the traveller in these mountain solitudes these days

20 August 1519

The route climbed again, up and over six thousand feet, passing through Coatepec, then on to Xicochilmaco, a walled fortress village and Aztec settlement

21 August 1519

The Spaniards continued the long, cold slog, day and night, ascending to a steep and mountainous pass that Cortés named Puerto del Nombre de Dios (now called Bishop’s Pass). Harsh winds hurtled down the narrow canyon, followed by a severe mountain storm that pounded Cortés and his men with rain and sleet and biting pellets of hail, soaking them to the skin. Three of the Cuban porters perished from exposure in the high mountains of the Cofre de Perote.

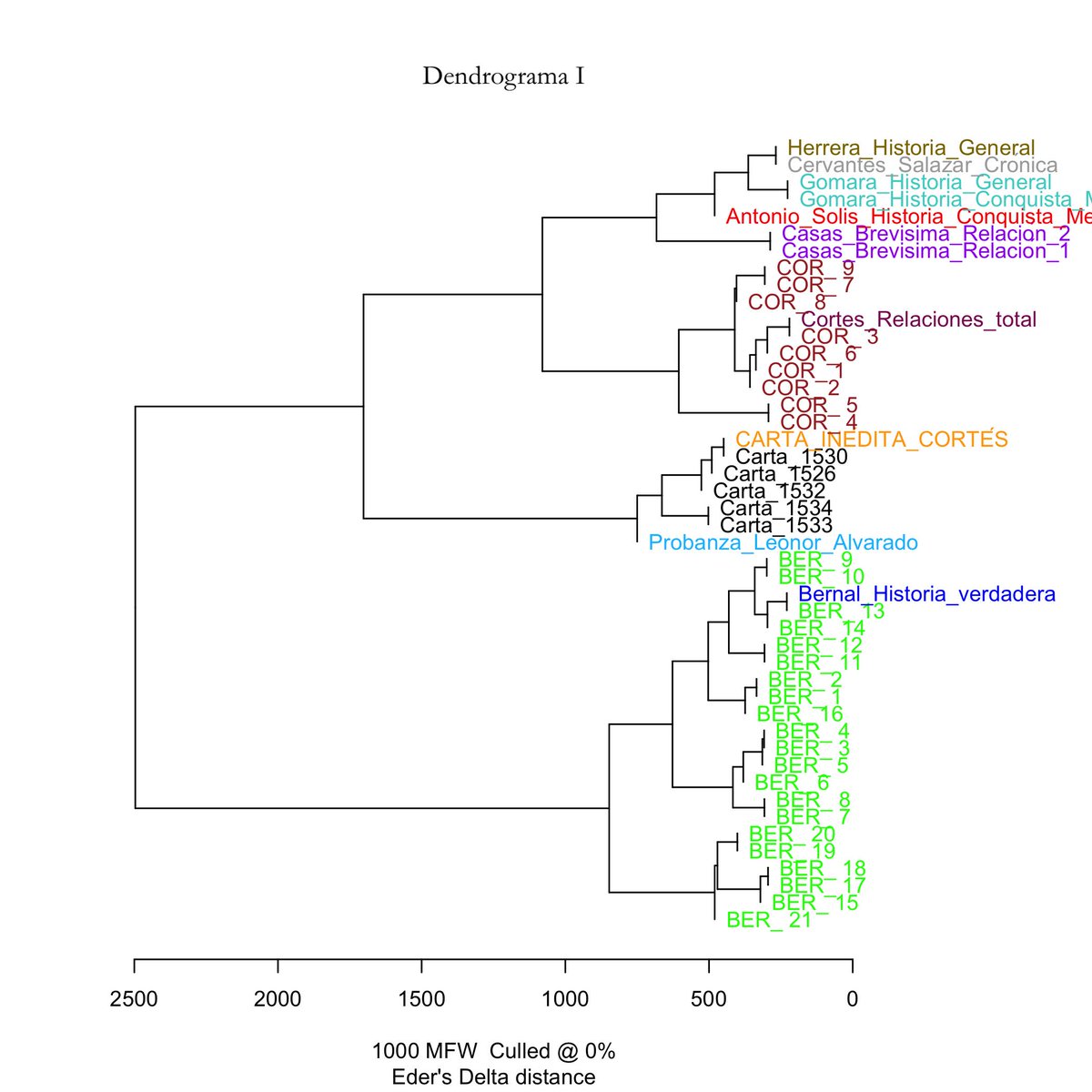

See this complete article, in Spanish: La graciosa y gratuita disputa sobre la autoría de la Historia verdadera del inconfundible Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Francisco J. Blasco Pascual http://revistas.rae.es/brae/article/view/216

J. Blasco results reproduced from his corpus at https://t.co/Qh0BH1kyhu?amp=1

22 August 1519

The train of conquistadors and bearers pushed on, descending now from the rugged highlands onto a vast and desolate plain, a dry and barren sun-pocked pan

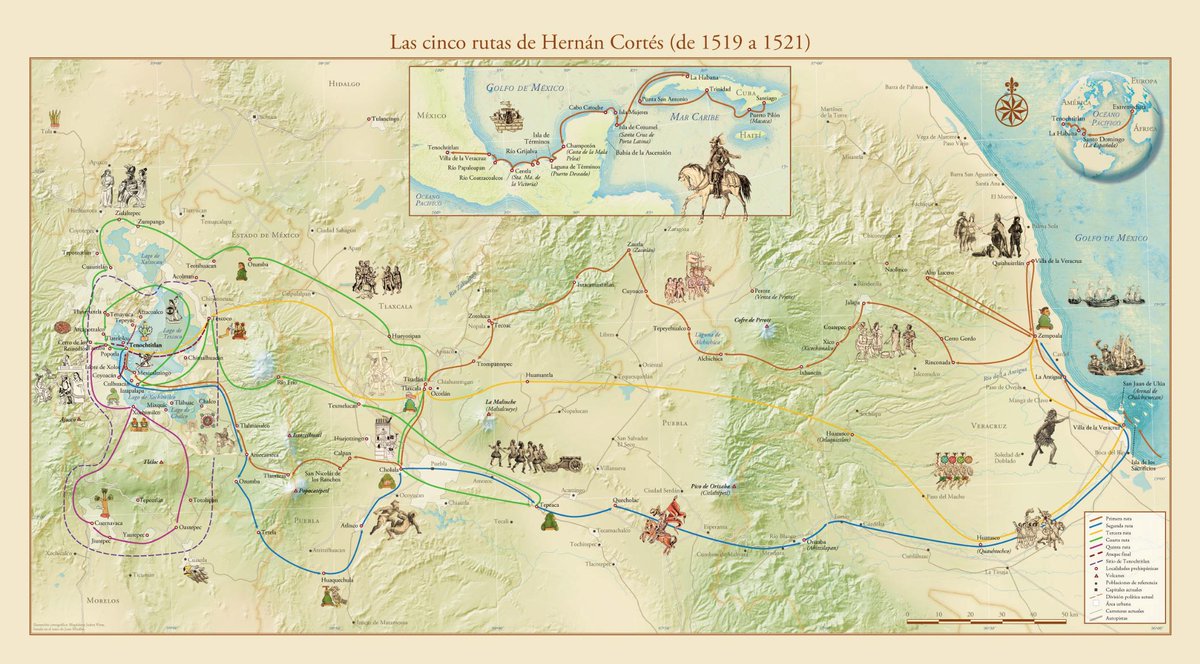

See ‘Las cinco rutas de Hernán Cortés’, by Juan Miralles, first digital edition 2013

23 August 1519

Cortés and his men swung north in the direction of the Río Apulco, skirting a massive salt lake, and marched for three days across the seemingly interminable plain, depleting all their stores of food and, worse, all their fresh water

24 August 1519

Cortés’ men, parched to delirium, knelt and sucked the water from brackish lagoons, but the salinity was so high it only made them thirstier, and some grew sick and vomited as they staggered along

25 August 1519

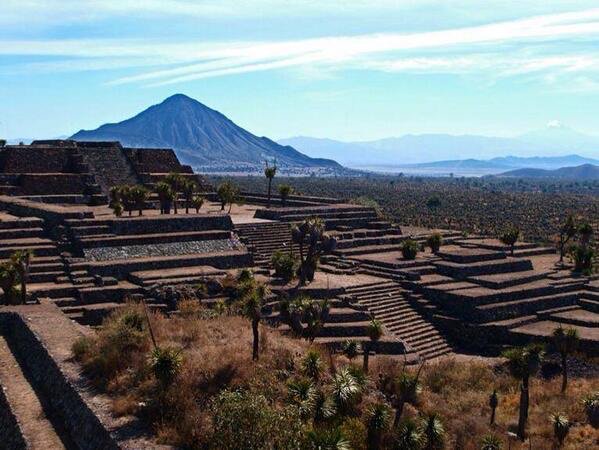

Constant march along narrow trails through the austere maguey desert surrounding the extinct volcano Cofre de Perote (also Nauhcampatépetl) 4,282 metres (14,049 ft) above sea level

26 August 1519

Across the seemingly interminable plain, around Alchichica lagoon, through Tepeyahualco to reach Santiago Xonacatlán. Map: https://bit.ly/33WV7hp

27 August 1519

Finally, after nearly a week of constant marching, they climbed again, as the austere maguey desert yielded to rough, flinty ridges. The narrow trails led Cortés’ men to the town of Xocotlán (now Zautla). Map: https://bit.ly/33WV7hp

Exhausted, scorched, and ravenous with thirst, the Spaniards were now dangerously vulnerable, but by good fortune Olintetl, the chief of Xocotlán, received them kindly, providing shelter, warmth, and food

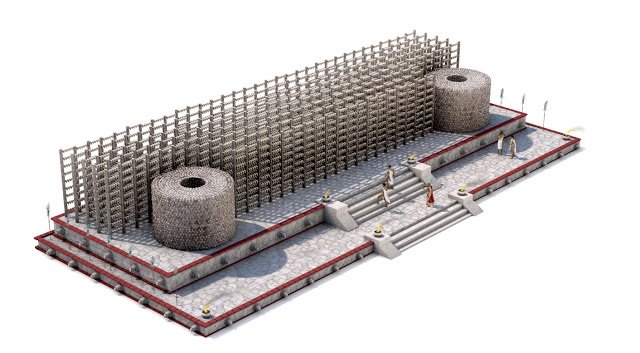

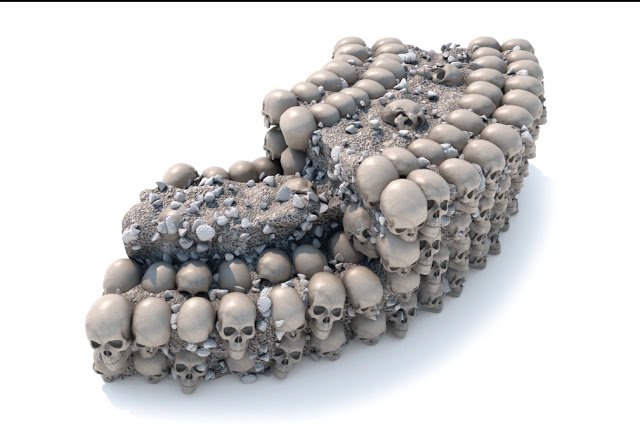

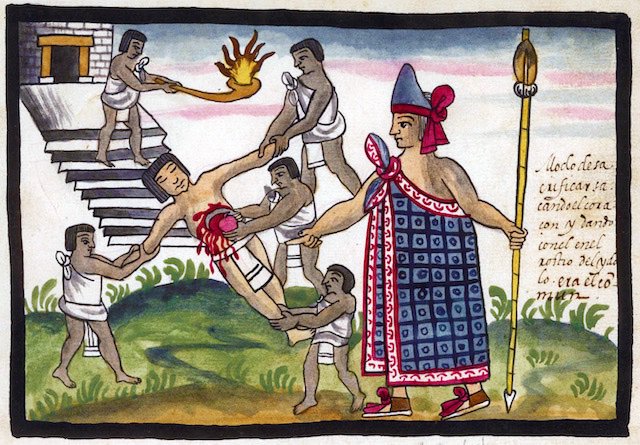

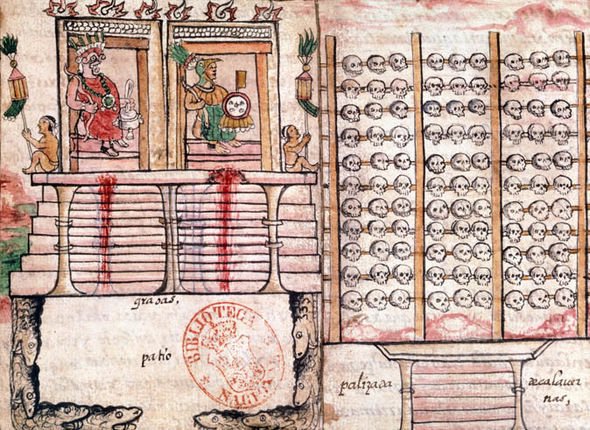

Once rested and fed, Cortés made an inspection of the town, which was by far the largest they had passed through since leaving the coast, with a population of several thousands. In the town square Cortés discovered a giant skull rack (or tzompantli) displaying human skulls arranged in neat rows, beside which were great piles of thighbones and arm bones bleached white and luminous in the sun. Most shocking and repugnant to Cortés were the fifty or so recently sacrificed corpses, disemboweled and bathed in blood, and a large statue of the war god Huitzilopochtli bespattered and still dripping with the lifeblood of these sacrificial offerings.

28 August 1519

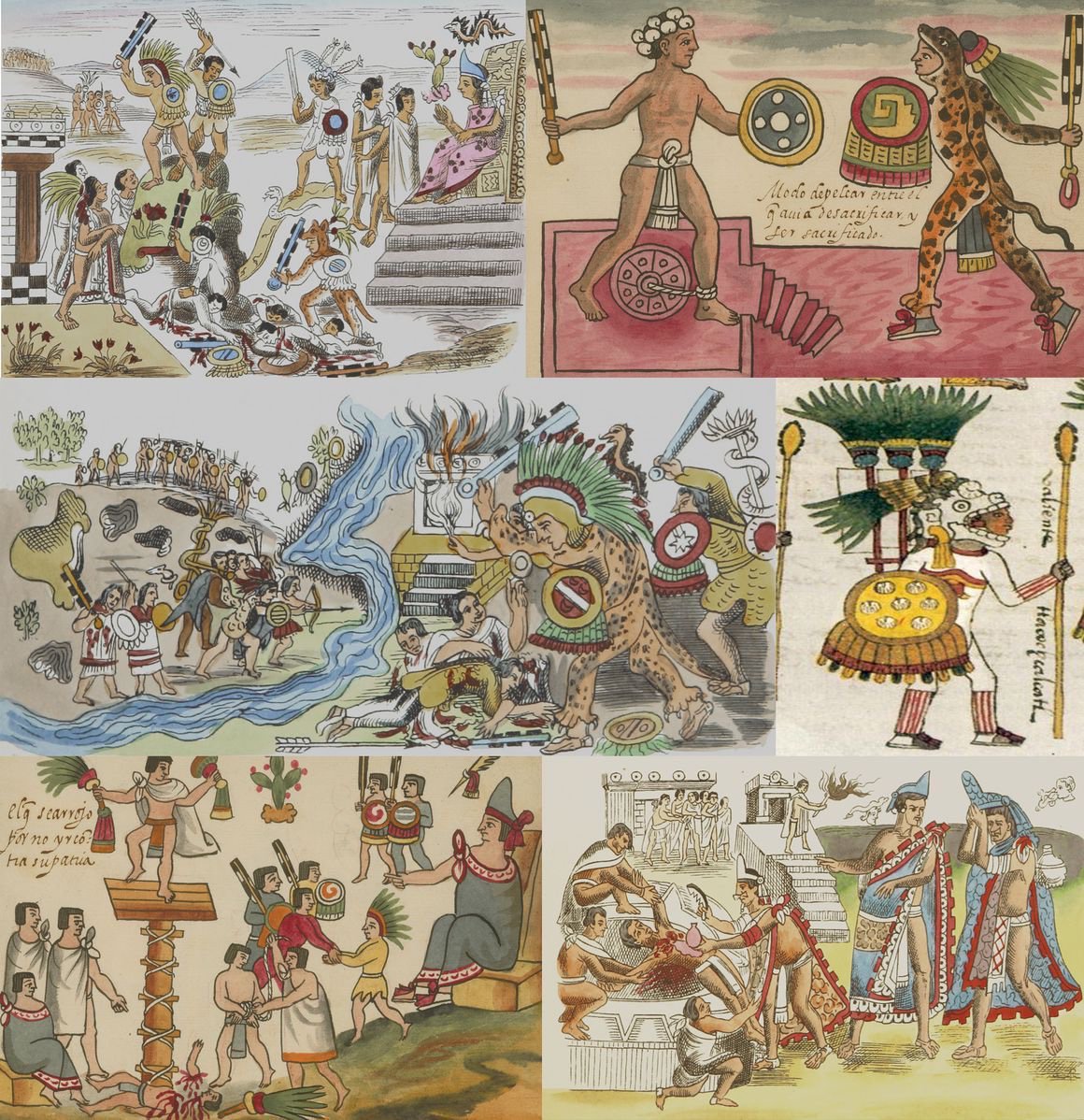

Human sacrifices, Aztecs believed, ensured the daily rising of the sun. War captives were ceremonially led to high altars and sacrificed by five priests who placed each victim on his back on a special stone that depicted the sun

Two priests held down the arms, and two more priests splayed and pressed down the legs. A final priest clamped a large collar around the prisoner’s neck while the village chief hoisted an obsidian blade high, then plunged it into the victim’s chest

Opening the cavity, he would then remove the still-beating heart with his hands and lift it in a highly stylized and ceremonial offering. The steam from the heart was believed to carry a special message to the sun

The skull racks, made from thousands of sacrifice victims, served as constant reminders of their religion’s immense power

Human ritual sacrifice also served to bring rain and ensure harvest, as well as fertility, enacted in the Feasts of the Flaying of Men, the Festival of Toxcatl, and the New Fire Ceremony.

29 August 1519

Cortés could not have understood that these skulls and corpses were the aftermath and remnants of complex and elaborate seasonal religious rituals that the native inhabitants considered essential, even vital for their survival

Such sacrifices, they believed, ensured the daily rising of the sun. What Cortés, in his idea of universal values, could not assume was to tolerate them. He had to proceed against the barbaric acts viewed from his catholic values

He could not look away. His vision was a complex one: a world empire subject to Charles V, who would become ‘monarch of the universe’ and which Cortés would help to found it by pressing on from Mexico, across the Pacific to the East

This vision was compounded as it was of Cortes’s own dreams of the conquest of Cathay, Erasmian and Imperial dreams of a universal empire, and Franciscan dreams of the conversion of mankind as the essential prelude to the ending of the world

30 August 1519

Olintetl, the chief of Xocotlán/Zautla, made a detailed description of the capital city Tenochtitlán, which he said was an impenetrable fortress on a great lake, accessible only by three major causeways containing removable bridges

The city’s beauty was indescribable, Olintetl said, adding that the reach and power of Moctezuma’s empire was so great that he had amassed riches of gold and silver beyond imagining, much of it won in his conquests over neighboring city-states

Cortés inquired whether Olintetl himself possessed any gold, as he wished to obtain samples to bring back to his emperor in Spain. Olintetl said he had some gold, but was unauthorized to give any to Cortés without the direct permission of Moctezuma

Cortés, miffed by the rebuke, replied that soon enough he would be getting gold directly from Moctezuma, whom he was on his way to visit. Before departing, Cortés sent four Cempoalan chiefs ahead toward Tlaxcala

They carried a message stating that the Spaniards were coming soon, in peace, hoping to forge an alliance. Cortés then asked Olintetl the best route to the Aztec capital. The chief recommended Cholula, a city and shrine sacred to Quetzalcoatl

Some of the Cempoalans traveling with Cortés counseled against this choice, arguing that not only was the route longer, but Cholula was a heavily fortified Aztec outpost, and additionally the Cholulans were not to be trusted

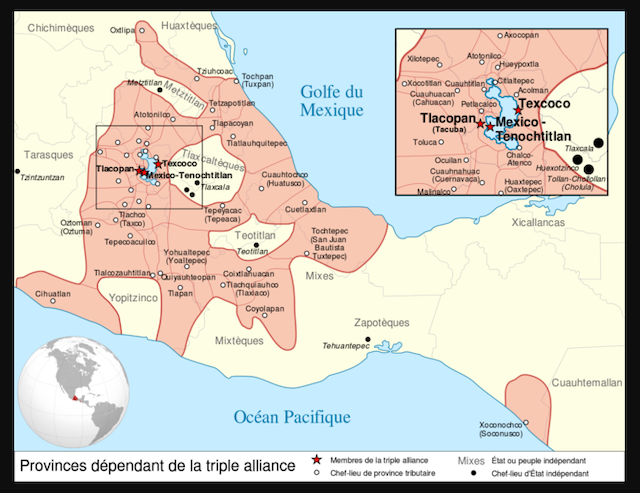

By contrast Tlaxcala, on an alternate route, had never been conquered by Moctezuma, and it was the Tlaxcalans’ allegiance that Cortés sought. Plus, the route through Tlaxcala was shorter. Cortés pondered the advice as he readied to leave.

The rested army moved out, snaking through the long valley of the Río Apulco, through a large town called Ixtacamaxtitlan. There they were also treated with guarded friendliness, apparently at the behest of Moctezuma

Moctezuma spies and messengers roamed far and wide and reported the Spaniards’ precise movements and locations.

31 August 1519

In Ixtacamaxtitlan, Cortés waited briefly for any response from his Cempoalan messengers, but there was no sign of them. Unknown to Cortés, his native messengers had successfully reached the capital of Tlaxcala and had presented the gifts, letters, and message to the nobles there; but they had been immediately imprisoned, their release pending an inquiry by a high council.

They were especially dubious of any claims of peace and friendship, suspecting that the Spaniards might well have formed an allegiance with the Aztecs and were going to attack them. The Tlaxcalan nobles agreed that rather than be passive, they would allow the Spaniards to enter their borders, then ambush them.

1 September 1519

Leaving the Zautla Valley, Cortés determined to take the shorter route toward Tlaxcala (through what is now Colonia Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, Tlaxcala) After about ten miles they approached a massive stone wall nearly ten by twenty feet

They had reached the formal border of Tlaxcala, the great battlement constructed to ward off Aztec attacks. Cortés’s men debated the virtues of entering the potentially hostile Tlaxcalan land, especially since the messengers had failed to return

The fiercely independent Tlaxcalans might view their entrance as aggressive. But the tremendous fortification’s single opening appeared unmanned, and deciding on action over discussion, Cortés urged his men through.

2 September 1519

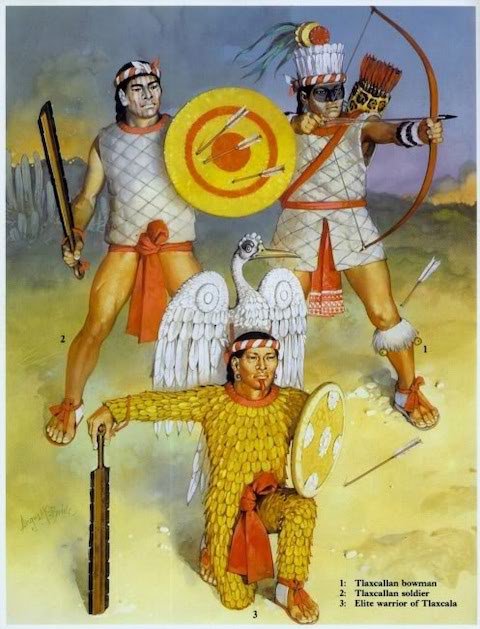

First battle with the Tlaxcala army: Xicotencatl Axayacatl, also known as Xicotencatl the Younger, was his leader. He used an ambush strategy: he first engaged the enemy with a small force of Otomí allies that feigned a retreat, and then lured the Spaniards back to a better fortified position where the main force waited. Then several thousands of Tlaxcalan warriors attacked but the Spanish drove them off with a concerted cavalry charge

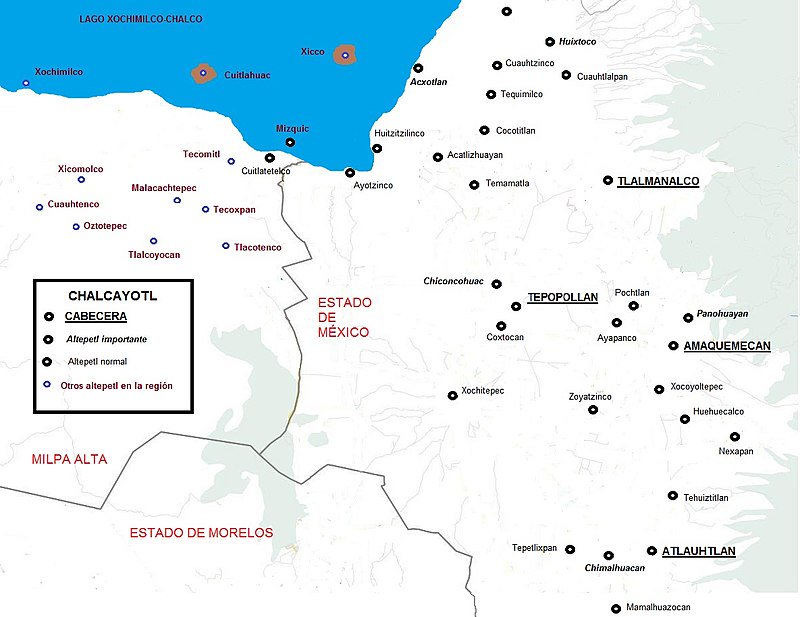

A powerful kingdom, Tlaxcala was a fierce rival of the Aztecs, never conquered by the Triple Alliance. It was a complex kingdom consisting of four parts (altepetl): Tepeticpac, Ocotelolco, Tizatlan and Quiahuiztlan

3 September 1519

Last night, Cortés and his men, hungry and exposed to the elements, laid in fear of what today might bring. Cortés brought Malinche and Aguilar to interrogate a few prisoners.

One of them warned Cortés that Xicotenga the Elder and his son, also named Xicotenga, were assembling more than 100,000 troops and that the Spaniards should surrender or else be defeated, captured, and then die at their captors’ hands

Undaunted, Cortés sent him away with a stern message: ”we come in peace and wish only to pass through your lands on our way to see and speak with Moctezuma. We come as your allies and brothers, but if we are further impeded, we will annihilate you”

When these released prisoners reached Xicotenga the Younger, he replied that “you could go to the town where my father was, and they would make peace with you by filling themselves with your flesh and honoring their gods with your hearts and blood.”

During the day, the Spaniards nursed their wounds, which were considerable, and advanced through Texcalac. Cortés must have been somewhat encouraged that only one Spaniard had been fatally injured in the battle yesterday in Tecoantzingo gorge

The goal of the Tlaxcalans (as later with the Aztecs) and indeed the design of their weapons, was to wound or injure in order to be able to take live prisoners for sacrifice, not necessarily to kill enemies on the battlefield Ver mapa

4 September 1519

Cortés arrived in Tzompantzingo. The Tlaxcalans did not attack. Instead, they sent a delegation bearing a significant amount of food, including more than three hundred turkeys and hundreds of baskets of fresh maize cakes

Though Cortés and his men needed and relished the food, he quickly surmised that these gifts were merely a ruse to allow spies to assess the condition of his men, animals, and weaponry

He immediately had these men arrested and confined, and he decided that next morning, fueled by the fowl and cakes, he would march and meet the Tlaxcalans head-on if they had not by that time agreed to a truce.

5 September 1519

The Spaniards sought a peace treaty with the Tlaxcaltecs. Maxixcatzin, the ruler of Ocotelolco, was in favour of allying with the Spaniards, but Xicotencatl II Axayacatl, ruler of Tizatlan, opposed this idea

Meanwhile, the governing council of the Tlaxcalans discussed whether or not to make an alliance with the Spaniards. They decided to send their army under Xicotencatl II

6 September 1519

Led by Xicotencatl the Younger, a massive army of around six thousand tlaxcalans swarmed the valley. But Cortés and his well-schooled divisions had planned for a mass attack, and his disciplined ranks held tight

It was a desperate battle, with terrible losses suffered by the Tlaxcalans, and the Spanish were reeling on the brink of defeat, and took refuge on a round hill named Tzompantepec. However, Spanish losses were again astonishingly minimal

Though fifty or sixty men had been wounded, and now all of the horses were cut and at least slightly injured, only one Spanish soldier is reported to have died that day, and Cortés made sure he could not be discovered by the enemy

By nightfall, both sides had returned to their own camps. With his men hungry and shivering, Cortés dispatched yet another messenger to Tlaxcala, reiterating his desire for peace and brotherhood.

7 September 1519

During the battle of Tzompantepec (Tzompantzingo = hill of skulls) Tlaxcalan numbers were so great as to prove a disadvantage. When they charged en masse, tightly bunched, they became easy targets for sustained crossbow volleys; the Spanish arrows mowed down dozens of warriors at a time. Artillerymen fired cannons into the mass—each heavy metal ball dropped many men and caused havoc and confusion among the Tlaxcalan squadrons, some of which dispersed.

Seeing this disorder, Cortés sent cavalry in teams of four, which would gallop out, their riders slung low, slashing the steel swords with devastating impact, cutting down warriors, then wheeling the horses back to their lines to rest and regroup, while another team went out. The Spanish horses and their riders, working in unison, became a killing machine, and the effect was terrifying for Xicohténcatl the Younger and his troops, who had never witnessed such efficient and frightening foes

To complicate matters, Xicohténcatl and one of his main captains were embroiled in a bitter dispute over tactics, so that even when directly ordered, this captain proved insubordinate, refusing to support his leader or dispatch troops to his aid.

Try as he might, despite sending wave after wave of his own men to their deaths, Xicohténcatl the Younger could not extricate the Spaniards from their position.

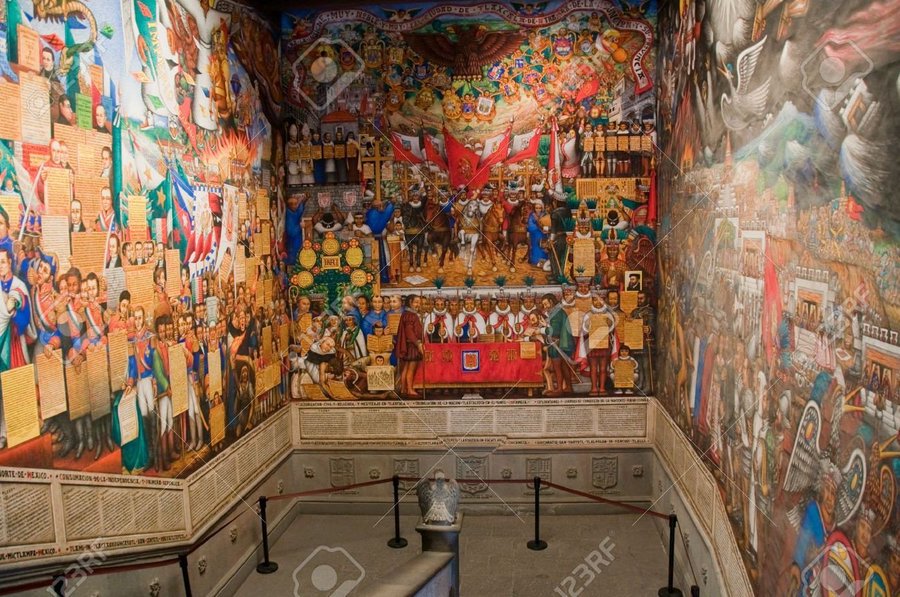

Note: Halfway along the Cortés route to Tenochtitlan, three key lessons: 1) this topic has been searched, and analyzed to its smallest details over 500 years, so there are tons of information available to find almost any answer; it is not exhausted though.

2) those who are content to try to find out who were the good guys and who the bad guys in this story can find multiple examples to choose their favorites, but they probably won’t understand this fundamental change for the world, and

3) Mexico today is the result of a series of amalgamations, accommodations, and recreations of cultures that are still dynamic, still being transformed today.

Note: Watch online a great documentary from historian Michael Wood Conquistadors (1) The Fall of the Aztecs, with real cover of the actual route of Cortés

8 September 1519

In Tlaxcala, the high council met, perplexed by their force’s failure in the battlefield and wishing to determine the reason for it. The council gathered their wizards, shamans and soothsayers to look toward the stars for answers.

They carefully studied the alignment of the constellations, consulted prophecies, and sacrificed many slaves, and after much contemplation, they returned to the council with the determination that though the Spaniards were not necessarily gods, still they received their power (as their own gods did) from the sun. Therefore they must be attacked at night, when their powers were diminished. The notion was debated vigorously, especially among the chief Tlaxcalan military advisers.

9 September 1519

After much argument, the high council of Tlaxcala agreed upon a night attack. As quietly as they could, some ten thousand Tlaxcalan warriors moved into position on the plain below Cortés’s encampment on the hill of Tzompantepec.

10 September 1519

The night was clear, Cortés’s sentries noted mysterious movements below and reported them immediately to him, who roused his men quietly and whispered commands to his captains

They were to descend the hill in small divisions, conceal themselves in ditches and low depressions in the ground and in the maize fields, and when ordered, they were to erupt from the ground in a counterambush

As the Tlaxcalans approached, Cortés took his cavalry and small, fast regiments of harquebusiers and cannons and caught the Tlaxcalans unprepared on the open ground

The vaporous shadows of the horses and their thundering charge, the lightning flashes and deafening explosions of cannon fire, sent Xicohténcatl ’s forces fleeing in terror

The horses easily overtook many, wounding great numbers and killing more than twenty. The rest fled to report the grim news of the defeat to their leaders and soothsayers. Word of Spanish victory would soon spread across the land, into Tenochtitlan

11 September 1519

Cortés was pleased by his night victory, though the warring was taking a toll on the men, some of whom were now hypothermic, and many, including Cortés, were suffering from malarial fever and salt deprivation

The mood in the camp was mixed, with some renewed grumblings among the ragged men about going home, and Cortés was forced to assuage their morale with promises of wealth, adding that it was better “to die in good cause than to live dishonored.”

12 September 1519

The Tlaxcalan high council met again, now utterly stymied. Many, including the sage Xicohténcatl the Elder, concluded that the Spaniards had proved themselves invincible during day and night, and he argued they ought to make peace

Maxixcatzin, the ruler of Ocotelolco, one of the four independent altepetl that constituted the confederation of Tlaxcala, again showed himself in favor of allying with the Spaniards and fight the Triple Alliance

But Xicohténcatl the Younger argued that he had seen the slain beasts and numbers of the soldiers wounded. They bled and died as men. Divided, the Tlaxcalans agreed to once more send messengers to the Spanish camp to discover what they might.

13 September 1519

About this time six Aztec nobles entered Cortés’s camp on the hill, where he had now been for over a week. Aztec runners and spies had kept the emperor apprised daily of the battles and outcomes between Tlaxcalans and Spaniards

Moctezuma seemed dismayed by the fierce Tlaxcalans’ inability to subdue their foes. Now he sent the Spaniards a small embassy and their servants bearing an array of gifts: cotton garments, some lovely feather pieces, and a good deal of gold

Cortés thanked the Aztec nobles kindly and willingly took the gifts but declined to return to Spain just yet. He insisted he had specific instructions from his own emperor to personally visit Montezuma, and he did not wish to disappoint his ruler

The Aztec nobles expressed Moctezuma’s congratulations on their successful battles and warned Cortés not to trust the Tlaxcalans. Then they proposed a deal. Moctezuma offered these gifts to Cortés and would submit to becoming a vassal of Spain, paying to the king an agreed-upon annual sum in tribute in the form of gold, slaves, women, and jade, if Cortés and his men would agree to return home immediately, forgoing their intended trek to Tenochtitlán, which would be too difficult anyway

He really had no choice in the matter. He bade them to return to Moctezuma, explain the situation to him, and request once more a formal meeting.

14 September 1519

A few days after the night raid, an entourage of fifty Tlaxcalans arrived with food, which revived the Spanish troops. The famished men were gorging on roasted fowls, warmed maize cakes, and local figs and cherries, when Malinche informed Cortés that a good number of these “messengers” were actually spies, for she had seen them inspecting the perimeter of the camp and making notes concerning the condition of the men and horses

Cortés, enraged, had the men arrested, then questioned under physical duress. He was able to induce confessions from most. They were indeed spies sent by Xicohténcatl to assess the camp and troops for signs of weakness

As brutal punishment and to send a definitive message, Cortés assembled seventeen of the Tlaxcalan spies and had some of their thumbs or hands amputated, then sent them back to Xicohténcatl with a clear warning: ‘Submit or we will destroy you’.

15 September 1519

At least some of the spies made it back to Tlaxcala to display their maimed hands, because then a delegation returned bearing much food and a message that soon the great warrior Xicohtencatl the Younger would arrive to make peace

16 September 1519

Cortés was still discoursing with the ambassadors of Moctezuma, and about to dismiss them, to retire to rest, for the fit of malarial fever was coming again, when it was announced that Xicohtencatl the Younger was approaching.

17 September 1519

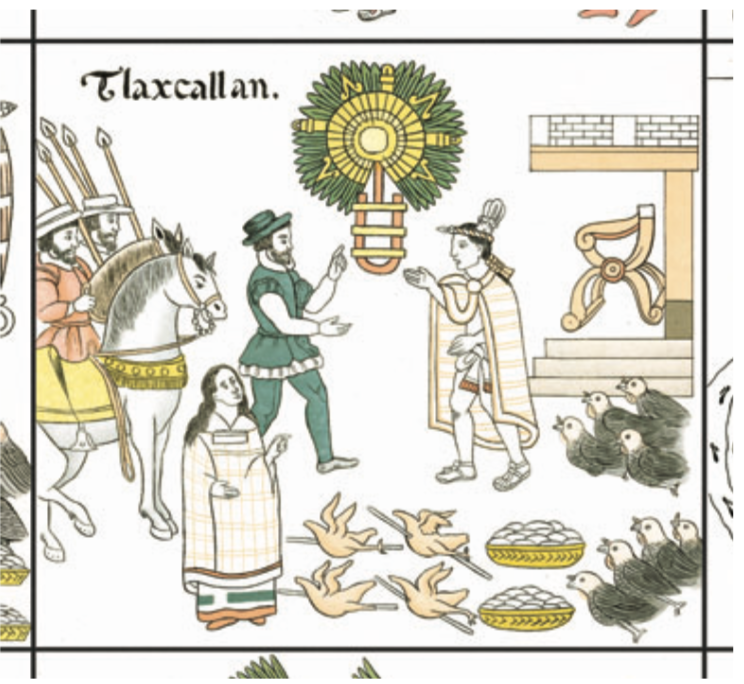

Peace with Tlaxcala: Xicohtencatl the Younger met with Cortés. He arrived surrounded by many other Tlaxcalan noblemen and chiefs from the four main towns

They brought some gifts, apologizing for their modest nature but explaining that they were poor and that effective trade for goods had been impeded by their Aztec enemies

The warrior told Cortés that he was impressed with the captain’s artistry on the battlefield and that the Spanish soldiers had defeated his finest, most skilled warriors. He apologized for the attacks on the Spaniards but explained that he had truly believed them to be allied with Montezuma and the Aztecs, their archenemies. The Tlaxcalans were a proud and defiant people, but now they were impressed and honored the Spaniards’ military superiority

They wanted a truce. Xicohtencatl the Elder would be willing to strike a deal— they would agree to become vassals of Cortés and his king, if he would allow them to accompany his army in an attack against Moctezuma

Xicohtencatl the Elder had extended a personal invitation for Cortés and his men to come to Tlaxcala to rest from their battles, where they would be hosted like royalty. Hernán Cortés nodded.

18 September 1519

The peace with Tlaxcala meant Cortés now had an army he believed sufficient to confront this man Moctezuma, whoever he was and however powerful he might be.

19 September 1519

The Mexican ambassadors advised Cortés against Tlaxcallans words of peace, and begged of him to remain for another six days in his present quarters, that they might first send messengers to Moctezuma, and would return again

To this Cortés consented, partly on account of his malaria, partly because he thought the warnings might not be altogether so unfounded as he imagined. In that time he could also gain more certain proofs of the real intentions of the Tlaxcallans.

20 September 1519

As the whole country from Veracruz up to the present quarters, was inhabited by friendly tribes and allies, Cortés ventured to forward a letter to Juan de Escalante, who had remained behind there in garrison

He desired him to complete the buildings, and then gave him an account of the great victories gained since arriving in Tlaxcala, and how Cortés had compelled the inhabitants to sue for peace

He also desired him to make a day of thanksgiving, and in every way to favour the Totonac allies. Lastly, he requested him two bottles of wine which he had buried in a certain corner of his quarters there, and some holy wafers, as they had none left

Escalante sent a speedy answer with the things Cortés required. It may easily be imagined how joyously this news was received at Veracruz.

21 September 1519

During these days Cortés erected a majestic cross in the camp, and had one of the temples in the neighbourhood cleansed and freshly plastered by the inhabitants of Tzompantenpec, and some other Indians

The postponement of the visit greatly distressed the caziques of Tlaxcala, yet they continued to send Cortés fowls and figs, and a daily supply of provisions. This they did with the best of good will, nor would they ever take anything in return

On the contrary, they daily more earnestly begged of Cortés not to delay his visit any longer, but he was eager to wait for the return of the Mexican ambassadors, and he each time put off the Tlaxcalan with some friendly excuse.

22 September 1519

Cortés was finally prepared to leave the rough and exposed hill of Tzompantepec (Tzompantzingo) behind. His men were elated to enter Tlaxcala

The Mexican ambassadors had returned from Mexico with a rich gift from Moctezuma, who was very pleased with the success of the Spaniards against Tlaxcala

Moctezuma requested Cortés most urgently not to bring any Tlaxcalans into his dominions, for whatever purpose it might be, and upon the whole not to trust them

Cortés accepted these presents with every appearance of delight, and thanked them, with the assurance that he would render Moctezuma good services in return

In the midst of this discourse several messengers arrived from Tlaxcala, bringing Cortés information that all the old caciques of the country were on their road to conduct Cortés’s expedition into their city

On learning this, Cortes requested the Mexican ambassadors to stay for three days before they departed again to their monarch with his answer; for that, at present, he was about to grant terms of peace to the Tlaxcalan chiefs

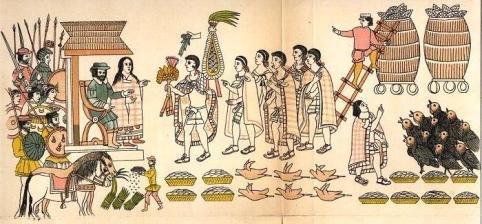

The caciques of Tlaxcala arrived to the camp. When they were in presence of Cortés they paid him the profoundest respect making three deep bows. They likewise perfumed with copal, touched the ground with their hands, and kissed it

They asked Cortés to accompany them immediately to the city. Then, with additional 500 porters from Tlaxcala, the next morning early Cortés men were finally enabled to set out for the metropolis of Tlaxcala.

23 September 1519

On this day, three weeks after the first battle with the Tlaxcalans, Cortés led his company to Tlaxcala. Here his bedraggled men and horses would rest for three weeks and recover until they were fit enough to continue on to Mexico

Thousands of curious onlookers lined the streets as the Spanish army approached Tlaxcala. Cortés and his men rode in as celebrated victors, the streets lined with flowers, and even inhabitants of outlying villages came to witness these strangers

Robed priests along the route burned incense, their black hair tangled and matted with dried blood; their ears, recently mutilated in ritual sacrifice, dripped fresh blood. After dismounting and formally meeting the blind Xicohténcatl the Elder, Cortés followed a procession of hosts to his quarters, where his men were put up in large flat-roofed stone houses and palaces, and all the horses, many lame and limping, were provided with comfortable quarters. The Totonacs were also given food.

24 September 1519

Cortés was moved by the organization and layout of the city, remarking in a letter to his king: “It is so big and so beautiful that all one could say about it would be unbelievable. It is bigger than Granada and better fortified. Its houses, its buildings, and the people that inhabit it are more numerous than at Granada at the time we conquered it, and very much better supplied with the produce of the land, namely bread, fowl, game, and fresh-water fish.”

25 September 1519

In Tlaxcala, Cortés spent a great deal of time, flanked by Malinche and Aguilar, in conversations with nobles, elders, and members of the high council, who were remarkably forthcoming

By day they visited the bustling central market, where thousands of people from the region came to trade. Still, though they were being treated as royalty, Cortés positioned sentries and guards and instructed his men to sleep armed and ready.

26 September 1519

The Spanish expeditionary force remained in Tlaxcala gorging on fish and fowl at feasts and enjoying the company of some of the three hundred native women given Cortés as a gift in lieu of gold

Cortés would accept them only if the Tlaxcalans would destroy their own idols and agree to give up human sacrifice; he later agreed to take them only if they were allowed to be baptized. Once they were baptized, Cortés distributed them among his men.

[Note from Pedro Carrasco ‘Indian-Spanish marriages’: according to Diego Muñoz Camargo, the rulers of Tlaxcala first presented Cortés with 300 female slaves, but later, ‘they gave their own daughters so that, by any chance any should become pregnant, the descendants of such valiant and daring men would remain among them’. Little is known about the individual unions of these Tlaxcalan princesses with Spaniards. Alva Ixtlilxochitl identified five of the princesses.

With the exception of doña Luisa Xicohténcatl, the daughter of one of the four rulers of Tlaxcala who was given to Pedro de Alvarado, they perished in the disastrous flight from Tenochtitlan in July 1520]

27 September 1519

Once their allegiance was formally and ceremonially sealed and Cortés had received assurances of significant Tlaxcalan military support, he inquired pointedly about many aspects of the neighboring Aztecs and their ruler Moctezuma

Xicohténcatl the Elder informed Cortés that the great city of Tenochtitlan was, and had been for as long as they could remember, highly fortified and impenetrable. The Tlaxcalans had managed to avoid complete conquest but only at very high costs

Moctezuma maintained strict embargoes and blockades that denied the Tlaxcalan people many important trade items, including cotton goods (needed for armor), coveted gemstones, precious metals like silver and gold, and salt

They went on to describe, using hand-drawn illustrations on stretched maguey fiber, the Aztec arts of warfare and weaponry and even crucial details about the city, such as the fact that all its fresh water came from a single aqueduct at Chapultepec.

28 September 1519

Cortés and Xicohténcatl had an interesting discussion of the generations-long Flower Wars. These were mock or staged battles between the finest warriors from each side, as well as young warriors hoping to prove themselves

More like competitions or tournaments than actual battles, these Flower Wars served a number of functions, including keeping the warriors practiced and trained for battle without killing them on such a scale as to deplete their forces

Most important, the winning side in a particular battle gained prisoners for human sacrifice, which both sides required (especially the Aztecs) in large numbers

Dressed in full regalia and fully armed, enemies confronted each other at predetermined battlefields and engaged violently but took precautions to injure and subdue rather than kill. Tlaxcalans and Aztecs had engaged in such staged wars for decades

Moctezuma later boasted that his armies could have legitimately conquered the Tlaxcalans with ease anytime he wished, but the protracted Flower War provided convenient training for his men and never-ending sacrificial victims.

29 September 1519

Roaming the city, some of Cortés’s men came upon the disturbing sight of prisoners of the Tlaxcalans bound and pinioned inside wooden latticework cages

The prisoners were fed daily rations of a special diet designed to quickly fatten them for sacrifice and consumption

Seeing these unfortunates and their condition, Cortés railed against such practices, hoping to impress upon the Tlaxcalans the teachings and truth of Christianity, about which he lectured long and often through Malinche and Aguilar

He even suggested to the elders and nobles the benefits of destroying their own idols and replacing them with his, showing them illustrations and pictures of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus

They should convert immediately, submitting to baptism to avoid burning in a fiery hell in the afterlife. The elders, including Xicohténcatl, balked. They had no intention of forsaking their own gods.

30 September 1519

As in Cempoala, Cortés favored a forced conversion, but once more the judicious Father Olmedo argued for prudence, pointing out that real and lasting conversion took time and religious understanding, and at any rate the Spaniards certainly had no need to create conflict and tensions with their brand-new allies. And once more Cortés had the good sense to take the advice of his trusted religious counselor

For their part, in a remarkable show of religious concession and tolerance, the Tlaxcalans provided one temple where the Spaniards could erect a cross and worship their idols

Here Cortés had his priests hold daily public mass; the ceremonies were attended not only by his men but by scores of the city’s inhabitants and those of neighboring villages.

1 October 1519

Buddy Levy in his book Conquistador says: ‘Although Cortés is sometimes interpreted as feigning devotion and piety as a justification for his actions and behavior, he appears to have been authentically, deeply religious.

As a product of his time and place, he could have believed in the rightness of his mission and viewed the conversion of the Mexican population—either forced, as he preferred, or by slower degrees and education—as actually bringing them salvation

Obviously Cortés believed that he had much to gain, but his religious zeal as he marched through the country was at all times evident and consistent. He was to that end the first man to sow the seeds of Christianity on the soil of the Americas’

Cortés would eventually found a college for theology students training for the priesthood, a hospital, and a monastery, as well as provide financial endowments for the building and maintaining of Catholic churches.

On this same day, Ferdinand Magellan left the island of Tenerife, resuming the Spanish expedition to the East Indies (1519 – 1522) resulting in the first circumnavigation of the Earth completed by Juan Sebastián Elcano

2 October 1519

In Tlaxcala, the Spanish men and horses and dogs were regaining strength, and Cortés discussed with his aides and captains their imminent departure to Tenochtitlan and the best route to take

3 October 1519

The Aztec ambassadors vehemently urged Cortés to take the route through Cholula; its leaders, they claimed, were complacent allies of the Aztecs, and there he could await final word on Moctezuma’s decision to meet Cortés in person

The Tlaxcalans disagreed, countering that the Cholulans could not be trusted—they were wicked and duplicitous people, and it might well be a trap. They argued for a route through the town of Huejotzingo, whose people were confirmed friends.

4 October 1519

After some meetings and contemplation, Cortés opted to take the Aztec ambassadors as guides and go through Cholula, a decision that turned out to have both political and tactical reasons

To appease the disgruntled Tlaxcalans, who were visibly unhappy about his decision, Cortés offered presents of cloth to Xicohtencatl the Elder and said that he would happily now accept his host’s offer of warriors to take along with him on his quest.

5 October 1519

The ship sent to Spain from Cortés on July 26th, 1519, Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, with pilot Alaminos and procurers Francisco de Montejo and Alonso Hernández Portocarrero arrived to Sanlúcar and then Seville

Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba whom Cortés had disobeyed, had successfully maneuvered to get the ship captured in Seville by his representative Fray Benito Martin

Fortunately, the intercession of Chancellor Gattinara and the King’s secretary, Francisco de los Cobos, prevented them from being judged right there for rebellion

However, Portocarrero died in prison (according to Historia de Yucatan, 1688, by López de Cogolludo) and Alaminos some time later. Montejo had a continuation of his history as a conqueror of Yucatan, with his son, from 1528-37

Montejo and Cortés’ father, Martín, were able to meet King Charles at the end of April 1520 in La Coruña, where they were able to present their case and Cortés’ treasure before the Spanish court

Charles I of #Spain was in a great hurry to embark on Germany to seize the crown of Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire as Charles V and, above all, he needed a large sum of money and gold to meet the responsibilities of the position

The courts of Castile (a representative assembly, or parliament) had to provide all these resources, which was one of the main causes of the subsequent War of the Communities of Castile, an uprising against the king and its administration (1520-21)

On May 20th, 1520, King Charles put to sea to wear the Emperor’s crown in Aachen, Flanders. He carried many Aztec jewels, and the gold and silver wheels that made such an impression on Albrecht Dürer, who could see them in Brussels in 27 August 1520

6 October 1519

Cortés diplomacy worked well, and the Tlaxcalan ruler offered an army of 100,000 men. Cortés thanked him for his generous support of his cause, adding that he would require only some six thousand at the moment.

7 October 1519

Bernal Diaz: ‘I have still to mention that in Tlaxcala we found houses built of wood, in the shape of cages, in which numbers of Indians, of both sexes, were confined, and fattened for their sacrifices and feasts.

We never hesitated a single moment to break them down and liberate the prisoners. These unfortunate beings, however, never dared leave our side, and this was the only means of saving them from being butchered.

Cortés gave orders to break open these cages wherever we came, for we found them in every township. We all showed our horror of these atrocities, and earnestly reproved the caziques for it, who then promised no longer to kill and devour human beings.

I say they promised, but that was all, and if we were but an instant out of sight the same barbarities were committed’

8 October 1519

The burning mountain of Popocatépetl was emitting more flames than usual, and Cortés and all Spaniards, to whom a volcano was something new, regarded it in astonishment

Diego de Ordás, one of the chief officers, entertained the bold idea to inspect this wonder more minutely, and begged leave of Cortés to ascend the mountain, who granted this request

Ordás took two men with him, and desired some of the chiefs of Huejotzingo to accompany him. They certainly did not refuse but tried to deter him saying that when he should have ascended the volcano, half way, he would not be able to advance further on account of the trembling of the earth, and the flames, stones and ashes which were emitted from the crater. They themselves never durst venture higher than to where some temples were built to the teules of Popocatépetl

And indeed they left Ordás when he arrived at that spot. The latter, however, boldly continued to ascend with the two soldiers until he had reached the summit.

9 October 1519

On preparation to march to Cholula, Cortés sent two captains, Alvarado and Vázquez de Tapia, accompanied by some Aztec messengers, in advance to view the great city of Tenochtitlan and inspect its strong fortifications and defenses

Tlaxcalans warned Cortés one more time: “Then you should be upon your guard with the people of Cholula, and against the power of Mexico in general”. Cholulans had failed to send an embassy to Cortés at Tlaxcala, as requested by the Spaniard

When the inhabitants of Cholula sent word that the reason why they could not go to Tlaxcala was because they were at enmity with its inhabitants, Cortés considered this excuse perfectly reasonable, and therefore resolved upon marching to Cholula.

10 October 1519

Cortés mustered for departure. With a train of Tlaxcalan and Totonac warriors and bearers that trailed for miles behind, accompanied by Moctezuma’s own ambassadors, Captain-General Hernán Cortés set out for Cholula

He was headed toward the city of Quetzalcoatl, the most important pilgrimage destination in ancient Americas. Legend held that in his journey from ancient Tula (now Mexico City) toward the Gulf Coast, Quetzalcoatl had made his first stop here

They marched most of the first day and camped that night on an exposed savanna; Cortés and his captains slept in slightly protected and sheltered ditches, with guards at watch.

11 October 1519

Delegates from Cholula arrived, bringing turkey and maize cakes; the priests waved burning braziers to fumigate Cortés and his captains, while the robed dignitaries beat on drums and blew reed flutes and conch shells

After some ceremony they invited Cortés and his men to come to Cholula, but they did not want the Tlaxcalans, their enemies, to accompany them. He thought about it, then acquiesced, telling the Tlaxcalans that they would need to wait outside the boundaries of the city proper while he conducted his business there. He appealed to their sense of pride by telling them that they could not enter because the Cholulans feared them.

Leaving the bulk of the Tlaxcalan force outside the city limits, Cortés led his expedition into Cholula. Later, Cortés would say that Cholula was “more beautiful than any city in Spain, for it is very well proportioned and has many towers.”

12 October 1519

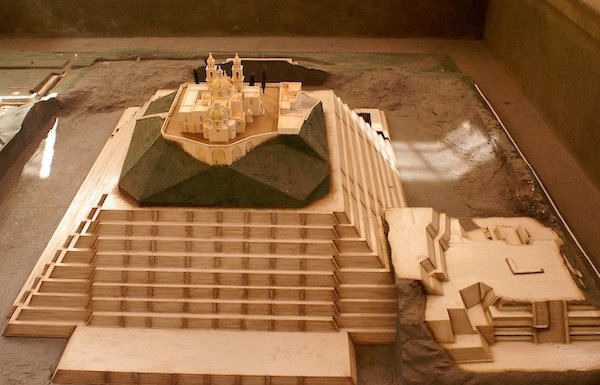

Having been continuously inhabited for more than one thousand years (first by Olmecs, later by the people of Tula), Cholula was remarkably well kept, and the Spaniards were impressed as they rode in

The great pyramid to Quetzalcoatl was a massive temple high on the hill overlooking Cholula. 120 steps led to the top of the structure, the largest free-standing man-made edifice in the world, twice as long as the great Egyptian pyramid of Cheops

Highly revered as the former home of the man-god Quetzalcoatl, hundreds of thousands of pilgrims came to this towering holy center annually.

13 October 1519

Organized and, to the Spanish mind, civilized (they noted freshwater wells), Cholula was a thriving city of more than 100,000 inhabitants, renowned widely for its fine pottery and craftsmanship in textiles, including jewelry

The Spaniards observed that the people here dressed in immaculate robes and took great care in their polished appearance. Cortés and his captains were well housed and cared for initially, the food supplies —always of vital concern— sufficient.

14 October 1519

Another group of Aztec ambassadors arrived and asked for a meeting with Cortés, during which they said the Cholulans had not the food stores to continue feeding the Spanish army, lest they themselves starve. Cortés doubted the claim

They also argued that the road to Tenochtitlán was dangerous, barely passable, and that in the great city Moctezuma possessed a magnificent zoo where fearsome animals like lions and alligators could be unleashed and set upon unwelcome visitors

This last was a thinly veiled attempt to keep the Spaniards from continuing their inexorable march toward the capital of the Aztecs. Cortés remained unmoved. He would take his chances with any savage beasts that might be loosed upon him.

15 October 1519

The food supplies did indeed dwindle, then stop altogether by the fourth day, when they were offered only water, and some wood, presumably to cook their own provisions

And visits by Cholulan lower representatives (important civic leaders, despite requests by Cortés, had yet to make an appearance) diminished as well

Some of his Totonac bearers reported to Cortés that they had seen many people, carrying goods and possessions on their backs, leaving the city, women and children among them.

More ominous still, rumors reached Cortés that large, covered trap-holes had been discovered in the streets, their bottoms lined with sharp stakes, and that a number of the city’s streets had been cordoned off, with warriors positioned on rooftops, sitting next to huge piles of stones. Cortés had to wonder whether the Tlaxcalans had been right to suspect a trap.

16 October 1519

Moctezuma himself may have played a role in the perceived plot to ambush the Spaniards. After he spent days in intense meditation an oracle came to him with a presage: the Spaniards were destined to die in the sacred city of Cholula

Believing this prophecy, Moctezuma immediately sent a division of his handpicked and best-trained warriors to Cholula, along with men carrying long poles to which they would tether the Spanish prisoners and lead them back to Tenochtitlán

Amazingly, a chance encounter by Malinche would propel Cortés toward his most uncharacteristic and perplexing act of the entire campaign. She had struck up a friendship with one of the local women, a wife of a Cholulan nobleman

The woman entertained Malinche in her home, fed her, and after a time suggested that for her own safety, Malinche should leave the Spaniards and come live with her—she could even provide a suitable husband, her son, for Malinche

Her husband was a captain in the Cholulan army, she informed Malinche, and the Cholulans, under Moctezuma’s orders, were massing a large force to attack the Spaniards on the road from Cholula to Tenochtitlán

For their assistance in the ambush, the Cholulans would be given twenty Spaniards to sacrifice themselves. If Malinche wished to escape imprisonment and probable death by sacrifice, she should seek refuge with her

But Malinche, now completely loyal to Cortés, convinced the noblewoman that she needed to get some things first, and she hurried to report her discovery to him. The mood in the city was tense and ominous, and the exodus of the townspeople continued.

17 October 1519

Acting quickly on Malinche’s intelligence, Cortés rounded up a pair of Cholulan priests and bribed them with jadestone gifts; when they remained tight-lipped, he tortured them into submission

The priests admitted that as far as they knew, Aztec forces were indeed stationed outside the city, along the route to Tenochtitlán. The Cholulans’ role was to help lead the Spaniards into the trap as they left the city

In preparation for a successful ambush, a special sacrifice was currently under way that included a handful of small children. Cortés quietly fumed at this last, then demanded at swordpoint that they go to the city’s chiefs and tell them that he wished to speak with them

When these nobles did arrive, Cortés calmly thanked them for their hospitality and informed them that he and his troops would be leaving in the morning so as to no longer burden the kind people of Cholula. They agreed to provide him with some bearers

Cortés promptly convened his captains to discuss the situation. They disagreed about the best course of action, some suggesting they return to Tlaxcala or at the very least, should they proceed toward Mexico, take an alternative route

But Cortés had another idea, a punitive preemptive strike that would send a message reverberating through the badland plains and all across the Valley of Mexico.

18 October 1519

Feigning preparations for departure, Cortés requested that all the lords of Cholula convene at the large central courtyard of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, where he could bid them farewell

Then he asked to speak with the leaders of the city, the main nobility, in his quarters. Once they were inside, Cortés barred the doors, accused them of conspiring with the Aztecs, said he knew of their plans and that for such treason they must die

The lords at first denied duplicity, but later blamed Moctezuma, saying that as his subservient tributaries they had had no choice. By now the courtyard of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl had filled with Cholulans including most of the city’s dignitaries

Cortés waved for a harquebus to be fired, his signal for the massacre to commence. Soldiers rode in and sealed off all the courtyard exits. The infantry—both Spanish and Tlaxcalans—rushed the crowded courtyard, wielding their swords and spears

They fell upon the mostly unarmed populace in wholesale slaughter. Arrows whirred in horrific volleys, scything down scores in minutes as musket balls plowed others. Women and children ran screaming, many trampled by horses or by fleeing people

Some priests managed to escape to the top of the high Temple of Quetzalcoatl, from which spot they feebly hurled stones to defend themselves or, despondent, took their own lives. Witnesses later reported:

“They hurled themselves from the pyramid, they also hurled the idol Quetzalcoatl headfirst, for this form of suicide had always been a custom among them, and to die headlong. In the end the greater part of them died in despair by killing themselves”

Cortés ordered the temple set ablaze, and it burned for two days straight. Within two hours nearly everyone who assembled in the courtyard had been slain. Uncharacteristically, Cortés then allowed the rest of his allied Tlaxcalans inside the city

For hours the Tlaxcalans pillaged and burned houses, looted and slaughtered people, until Cortés determined to put a stop to them. By the time Cortés halted the butchery, nearly five thousand people lay dead on the stone streets of Cholula.

Fray Bernardino de Sahagún in https://bit.ly/2KdZ746 (Códice Florentino) “The Cholulans did not carry offensive or defensive weapons, but were disarmed thinking that what was done would not be done, in this way they died a bad death”

19 October 1519

A great deal of gold and other precious items was looted from the palaces and homes of the nobles, and Cortés confiscated everything he could—though he had difficulty getting some back from the Tlaxcalans

Cortés ordered his men to clean the corpse-strewn city, removing the dead and scrubbing the place. What priests and nobles remained alive were brought forth, blamed for the slaughter, and instructed to send for their escaped friends and relatives

No more harm would be done to them. Though this must have been difficult for them to believe, in time people did reluctantly start to return. Prisoners were released, and after a few days a semblance of order was restored.

20 October 1519

As he had in Tlaxcala, Cortés found caged victims, including children, being held and fed for sacrifice, and he angrily broke the wooden bars and freed them. He instructed the Cholulan priests to cast aside their gods in favor of his

They agreed in principle to become allies and vassals, subject themselves to Spanish authority, but as to the question of gods, they hedged, and once more Father Olmedo counseled Cortés to give conversion time.

21 October 1519

The Aztec ambassadors had remained safely in hiding during the massacre, and now Cortés used their fear to his advantage. He told them that though the Cholulans had blamed Moctezuma for planning an attack, he did not believe them

Cortés intimated that he still planned to march on Tenochtitlán, and he hoped and trusted that Moctezuma would receive him peacefully. The Aztec ambassadors asked to send messengers to the capital to discover Moctezuma’s wishes. Cortés allowed it.

22 October 1519

With the massacre, Cortés had ensured a safe route between Cholula and Veracruz, which he figured would be crucial for resupply of arms, powder, and even men and horses, should any arrive from the islands

The smoke from the burning temples died down after a few days, and to alleviate continued Cholulan fears, Cortés again stationed most of the Tlaxcalans outside the city, but only after the two sides had agreed, begrudgingly, to a truce

Cortés and his men remained there, fed and hosted, for nearly two weeks, but the massacre sent shock waves through the land long afterward.

23 October 1519

When the messengers arrived in Tenochtitlán with explicit and detailed descriptions of the bloodbath in Cholula, Moctezuma was stricken and perplexed. This style of slaying defied all protocols of traditional Aztec warfare

Even more confounding, Cholula was the spiritual house of Quetzalcoatl—how could his own shrine have been desecrated? It was inconceivable. The massacre cast doubt that this Spaniard, this Cortés, was really Quetzalcoatl. Who, then, was he?

24 October 1519

Moctezuma gathered a dozen of his highest priests to contemplate the matter. Cortés could still be a god, but which one? He might be a god of war, a demon of darkness, a deity of justice or punishment

Moctezuma wondered what else he could possibly do to prevent these beings from arriving, or perhaps their arrival was preordained and could not be stopped. Maybe it was indeed the will of the gods

25 October 1519

For a week Moctezuma remained alone, aloft in the temple sanctuary, fasting and waiting for signs. In the thin air he was visited by Huitzilopochtli—the hummingbird, god of war and sacrifice—who communicated with the emperor

After listening carefully to his gods, Moctezuma at last left his sanctuary and descended the pyramid steps. He had come to a decision: the emperor would be willing now to meet Cortés.

26 October 1519

Aztec runners arrived at the Cholula city gates, runners sent from beyond the high mountains. Behind them trailed emissaries who asked for Cortés

Before him they laid offerings of food, many garments of the finest cloth, and, most impressive, ten plates of solid gold. The gods, and Moctezuma, had spoken. The emperor formally invited Cortés to come to Tenochtitlán.

27 October 1519

When the caziques of Tlaxcala knew that Cortés was determined to march to Tenochtitlán, they tried to dissuade him once again from marching to a city of such vast extent and power, and several means to carry out a murderous war

The Mexicas certainly, someday, would fall by surprise on the Spaniards and would not escape alive. However, they offered Cortés 10,000 of their warriors, under the command of their most capable generals, with a sufficient supply of provisions

Cortés thanked them for their kind offer and explained that it would not be appropriate to enter Tenochtitlán at the head of such a large army, particularly because the hatred between them and the Mexicas was so great

A thousand men were all he needed to transport the artillery and everything else, and clear the road to Tenochtitlán that had been obstructed to prevent its advance

Cortés also ordered that three of the Aztec ambassadors stay to show him the way, while the others were sent to Tenochtitlán, to inform his monarch that the march to the capital of his empire was ready.

28 October 1519

The chiefs of Cempoala, who had remained with Cortés all this time, hoped he would return with them to Cempoala. They were determined not to march to Tenochtitlán, as they were convinced it would be the destruction of the expedition

All Cortés pleas, added to Marina’s friendly advice, were fruitless, and they decided to return. Cortés cried out: “God forbid that we should force these people, who have rendered us such valuable services, to go with us against their inclination!”

He then ordered several packages of the very finest cotton stuffs to be divided among them, and likewise sent Xicomecóatl, the fat cazique, two packages for himself and his nephew Arexco, who was also a powerful chief

Cortés wrote to Juan de Escalante in Veracruz, with all the news and mentioning they marched westward. He warned him to watch carefully the inhabitants of the country, and desired him by all means to hasten the completion of the fortress, and to take the inhabitants there under his protection against the Mexicas, and also not to molest them in any way. This letter was given in charge of the Cempoalans, and they then prepared the march forward with every military precaution.

29 October 1519

Cortés spurred his horses and men westward. They rose, the Spaniards and their great train of allied warriors in tow, winding up the scrubby sierra separating the vast plateaus. Looking up they glimpsed the huge volcano Popocatépetl

On the first day they arrived to Calpan, subject to Huejotzingo, where they found all the chiefs assembled, who were friendly with the Tlaxcalans. They presented Cortés with provisions and a few trinkets of gold

They instructed Cortés about the road he should take, as soon as he had left the mountain pass behind. The expedition should reach two wide roads, one of which led to Tenanco Tepopollan (today Tenango del Aire), the other to Tlalmanalco

One of these roads was in excellent conditions, and the other had become impassable by a large number of big trees that had been felled and thrown across the road. On the first road, a little further up the mountain, there were Aztec troops ambushed

Therefore, they advised Cortés to get out of that road and go by the one that led to Tlalmanalco, which was hampered by trees. They would lend the Spaniards enough hands to clear this road, in which they would be assisted by the Tlaxcalans.

30 October 1519

Cortés lurched slowly up through the timbered foothills and then into the higher mountains. Men, sickened by great heights such as they had never before encountered, bent at the waist, coughing and gasping for air

The horses stumbled up the rocky trails, heaving and wheezing. They progressed slowly, only a few miles each day, passing through tiny scattered villages where they would rest a day, then press upward as biting winds hurtled down the narrow gorges; the poorly clad lowland and island bearers shivered through the nights. The Spaniards in full armor fared better, but they teetered as they climbed, burdened by the weight.

31 October 1519

Following a track between the two mountains, now called the Pass of Cortés, the company arrived to a fork in the main path. One of the roads was open, the other having been blocked with trees and boulders, as it was said in Calpan

Cortés, as advised, determined for the hard road, and they marched through the mountains in the closest possible order. Sending Tlaxcalans forward to clear away the heavy trees, the expedition began to descend

An early winter storm fell, fog and mist encircling them and snow coming down. Cortés ordered camp made, using some of the downed trees barring their passage as shelter. They struck fires as they could, though the place was wet and windy

The night was deathly cold; men convulsed in their armor, and the natives hunkered together to warm each other. Some of the captains found abandoned shacks, perhaps used by merchants, and sought shelter there.